Fate of strategic Musandam peninsula with new sultan in Oman

Maintaining security of the Musandam Peninsula will remain a top priority for new sultan, say analysts.

by Gordon Robinson

Western governments, as well as Oman’s Arab neighbours, are sure to seek reassurance from new Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al Said that Oman will continue to serve as a counterweight to Iran, which controls the opposite shore of the Strait of Hormuz [File: Sultan Al Hasani/Reuters]

Viewed from outside the region, the attention generated earlier this month by the death of Sultan Qaboos, may seem puzzling. Almost every obituary described Qaboos’s quiet, yet outsized, role in regional diplomacy. Less obvious for some may be why Oman was able to claim such a role in the first place.

Qaboos himself deserves much of the credit. A quietly charismatic figure, he inherited absolute political power but only relatively modest wealth (Oman’s oil resources are a fraction of those available to other Gulf countries), and used these to transform a place known for its remoteness and lack of development into a modern nation.

Some of it, however, was also geography. Tourists making their way through the old souk of Muscat, Oman’s capital, do so in the shadow of a 16th-century Portuguese fort that is still used by the Omani military today. A couple of centuries after the fort’s construction, the British turned up concerned – like the Portuguese before them – with safeguarding their route from Europe to India.

Control of Musandam

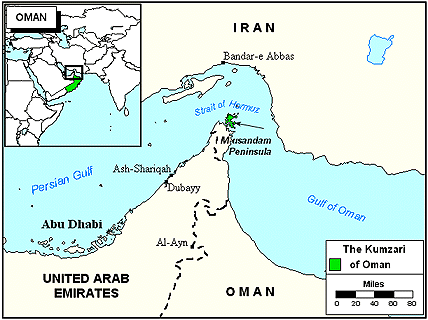

In the 20th and 21st centuries, what makes Oman geographically critical is its control of the Musandam Peninsula, the finger of land that forms the southern coast of the Straight of Hormuz. One-sixth of the world’s oil passes through the strait – more than 17 million barrels each day.

The Musandam is a remote and largely undeveloped area. Well into the 1990s it was a closed military zone, off limits to tourists and casual travellers. It remains sparsely populated and is rarely visited by outsiders, a fact reinforced by it not being connected to the rest of the country. To reach it from the rest of Oman, one must cross about 80km (50 miles) of the UAE.

“It is a bit unique in being separated from the rest of the country, and the area is incredibly strategic sitting right on the Hormuz,” Elana DeLozier, a scholar who focuses on the Gulf at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told Al Jazeera.

She says the Musandam’s security will remain a priority for the new sultan and his government.

Omani control of the strategic peninsula in part allowed Qaboos to pursue a largely independent foreign policy while maintaining ties with the Gulf states, Iran and western states. In recent years, Oman hosted talks that led to Iran’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers while it has remained neutral in the GCC crisis sparked when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt imposed a land, sea and air blockade on Qatar in June 2017.

Western governments, as well as Oman’s Arab neighbours, are sure to seek reassurance from new Sultan Haitham that Oman will continue to serve as a counterweight to Iran, which controls the opposite shore of the strait.

An extra complication – Oman’s borders with both Saudi Arabia and what is now the UAE – were unsettled for decades. Bitter and sometimes violent clashes were the norm as recently as the 1950s and 60s.

Though Haitham’s fellow Gulf rulers have a strong interest in maintaining the status quo in the Musandam and through the Strait, that may not prevent them from seeing whether he will be as independent minded as his predecessor, say analysts.

“Oman’s independent foreign policy has been an irritant for Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and, by implication though to a lesser extent, the Trump administration,” said Mehran Kamrava, director of the Center for International and Regional Studies at Georgetown University’s satellite campus in Qatar.

“If anyone is going to test the resolve of the new sultan, it is the Saudis and the Emiratis, particularly the latter, with whom the Omanis have had border issues in the past,” Kamrava tells Al Jazeera. “Saudi Arabia has long had hegemonic ambitions in the Arabian Peninsula – hence its history of tensions with Qatar – and under [Abu Dhabi Crown Prince] Mohammed bin Zayed’s leadership, the UAE has been seeking to reshape the political and diplomatic map of the Middle East.”

Kamrava added that “Oman has steadfastly resisted these converging trends” but that it remains to be seen what will happen as the sultanate’s new leadership settles in.

If anyone is going to test the resolve of the new sultan, it is the Saudis and the Emiratis, particularly the latter, with whom the Omanis have had border issues in the past.

MEHRAN KAMRAVA, DIRECTOR OF THE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL STUDIES AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY’S SATELLITE CAMPUS IN QATAR

Rising economic challenges

The transition of power – though long anticipated (Qaboos had been in failing health for several years) – comes at a time of rising economic challenges that are likely to make Haitham’s job more difficult.

The country’s budget deficit grew rapidly after the 2014 fall in oil prices and despite efforts to diversify the economy, oil and its related industries account for nearly three-quarters of Omani government revenues.

The waning months of Qaboos’s reign saw Oman sell off stakes in its gas pipelines and main electric company to foreign investors.

“Oman will need to rely on other governments as well as international capital markets for financial support in the near term,” Karen Young, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, tells Al Jazeera. “It has economic vulnerabilities, but it also has an opportunity to liberalise its economy and choose partners for future growth.”

For all these reasons, observers in the region and beyond will pay close attention to how the new sultan chooses to run his government. Qaboos’s administration was said to be intensely personal, with the ruler becoming involved in matters most heads of state would barely notice.

A drive around Muscat reveals window-mounted air conditioners that are always concealed from view inside artful wooden boxes. Omani law requires this, and popular legend says it does so because Qaboos found AC units to be unsightly. The story may be apocryphal, but the fact that it is widely believed says a lot about the way Qaboos ran his kingdom for nearly half a century.

Qaboos famously held nearly every important cabinet portfolio himself. Haitham “is likely to try and retain as much personal control over the Omani state as possible. However, it would be extremely difficult if not impossible for him to replicate the same patterns of personalist rule as Sultan Qaboos practiced,” Kamrava said.

DeLozier notes that unlike his predecessor, Haitham has two brothers – Assad and Shihab – “so the family dynamic will likely shift a bit”.

Over the years, Sultan Qaboos became one of the Middle East’s essential diplomatic figures – a man whose influence only grew as the decades passed. His cousin has immense shoes to fill. At home he must build a legacy of his own while respecting the memory and accomplishments of a predecessor who is personally associated with almost every aspect of modern Omani life.

On the international stage, analysts say, he will need to demonstrate quickly that Oman remains a trusted custodian of one of the world’s most important waterways, and a trusted interlocutor who can talk candidly with both Washington and Tehran.

“The new sultan,” said Young, “will reign in a time of transformation, much as Sultan Qaboos did.”

- Previous President Trump hails US farmers for help in trade war with China

- Next Afghan Electoral Bodies Divided on Recounting Controversial Votes