27 cities – the pillars of Soviet-era industrialization to heavy to revive: Kazakhstan’s Rust Belt On a Path of Decline

@dreamstime

The onset of winter in 2025 served as a stress test for Kazakhstan’s industrial north, and by most measures, the country passed. After high-profile heating system failures in cities such as Ekibastuz and Ridder in previous years, when entire neighborhoods were left without heat in temperatures as low as minus 30 degrees Celsius, the authorities were forced to move beyond piecemeal repairs toward large-scale emergency interventions.

The state invested unprecedented resources into overhauling heating networks and modernizing thermal power plants in single-industry cities and smaller industrial settlements across the region. Significant budget allocations helped stabilize the most vulnerable infrastructure. Emergency repair calls gave way to routine updates from local authorities, and utility breakdowns shifted from the realm of crisis to that of manageable risk.

By this winter, the basic issue of urban survival had been resolved. For regions with aging infrastructure and high industrial dependency, this marked a crucial transition from systemic failure to fragile stability.

The Future Votes with Its Feet

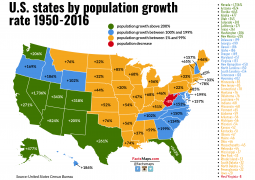

Yet behind the upgraded pipes and boilers lies a deeper structural issue. Cities such as Ekibastuz, Rudny, Temirtau, Balkhash, and many others were pillars of Soviet-era industrialization. In today’s market-driven Kazakhstan, many are rapidly losing both economic relevance and population. The term “rust belt,” borrowed from post-industrial regions of the United States, has increasingly entered national discourse.

While the state focuses on fixing infrastructure, residents are asking a more fundamental question: do these industrial cities have a future? The answer, many argue, lies not in kilometers of new piping but in people, and the data is clear. Single-industry cities are aging and shrinking. Even where wages exceed 1,200 dollars per month, well above the national average, young people are still leaving.

The issue is less about income than about quality of life. A stable job is no longer enough for younger generations. They also want livable cities, modern schools, safety, leisure opportunities, and green spaces, amenities these places often lack. As a result, migration from northern and eastern regions to Astana and Almaty continues, fueling an imbalance. The megacities are overstretched, while industrial cities face growing labor shortages.

Exceptions to the Rule

Amid the general decline, the city of Saran in the Karaganda Region stands out as a rare success story. Just a decade ago, it was a struggling mining city facing significant population outflow. Today, it is a flagship of Kazakhstan’s single-industry city revitalization program.

Saran’s turnaround hinged on radical economic diversification. The establishment of an industrial zone and the arrival of new anchor investors not tied to coal mining fundamentally changed the employment landscape. The launch of the KamaTyresKZ plant, along with household appliance manufacturers and the QazTehna bus assembly plant, has stimulated both economic and social development.

Authorities now point to Saran as proof that a single-industry city can transition into a manufacturing hub under the right conditions. However, its success is also attributed to unique logistical advantages, notably proximity to Karaganda and substantial state support.

Replicating the Saran effect in more remote cities such as Arkalyk or Zhezkazgan will be far more difficult.

Ecology Versus Wages

Cities such as Temirtau, Rudny, and Ekibastuz face a different challenge: economic dependence on a single, often polluting, employer, typically a national or quasi-state industrial giant. In these places, a growing tension exists between relatively high wages and poor environmental conditions.

Temirtau is emblematic. Despite changes in ownership of its metallurgical plant and promises of cleaner operations, the city continues to suffer from chronic air pollution. While modernization of the local power plant has improved heating reliability, it has done little to improve environmental conditions. According to Kazhydromet, air quality remains hazardous year-round, making these cities increasingly unattractive, particularly for families with children.

At the same time, many residents fear the closure of these polluting industries, as they remain the only significant sources of employment.

Controlled Contraction

The reality is that not all of Kazakhstan’s 27 single-industry cities can be revived. This view, while rarely stated directly, increasingly appears to inform government policy. A once-universal strategy of revival is gradually giving way to a more differentiated approach.

Some settlements, including the city of Saran and the towns of Kulsary and Aksay, are being positioned as future growth centers, with the potential to integrate into the broader national economy. Others may face a model of managed contraction, in which the state maintains basic infrastructure and social services while quietly encouraging gradual population resettlement to more viable regions.

The modernization of power plants has granted Kazakhstan’s rust belt a temporary reprieve. The central question is how this time will be used: to redefine the economic future of these industrial cities, or simply to delay the inevitable for a few more warm winters.

- Previous Takaichi and ‘wine-and-dine’ politics

- Next Thailand removes Hindu statue to control border area