Burma’s Hopeful Pictures Greater freedom and a growing economy have led to a golden age for photography in the country.

Rangoon, Burma

‘These days, everyone has a camera in their pocket,” photographer Christophe Loviny says. “We don’t have to focus on the technology, so we can concentrate on the thinking, on storytelling and methods.” The longtime Asia photographer does exactly that, spending most of his time training the next generation of local photographers and celebrating their work.

A co-founder of Cambodia’s Angkor Photo Festival, Mr. Loviny is involved in photography programs in China, Indonesia and soon the Philippines. But his greatest legacy may be in Burma, a country known until recently for its extreme censorship. For nearly a decade, Mr. Loviny has organized the astounding Yangon Photo Festival. The ninth edition opens Friday, with exhibitions and projections continuing through March 19.

The program is larger and more ambitious than ever before. The centerpiece is a massive exhibit of the best international photojournalism, from the World’s Press Photo Awards, to be shown outdoors in a park across from Yangon City Hall. This would have been international news just six years ago, and even today remains an achievement.

The festival features a strong mix of Burmese stories, by locals and the global press, as well as archival treasures. For example, “Yangon Fashion 1979” offers black and white portraits from Bellay Studio, one of the few places locals could dress up. Merchant seamen smuggled in foreign clothing, which the studio secretly kept in its vaults.

The exhibits also include rare photos from the early 1900s by James Harry Green, a British officer who traveled around Burma recruiting soldiers. Mesmerized by Burma’s beauty and diversity, he became an accomplished photographer and later an anthropologist. “Burma Frontiers” showcases his fascinating black-and-white portraits for the first time in Burma.

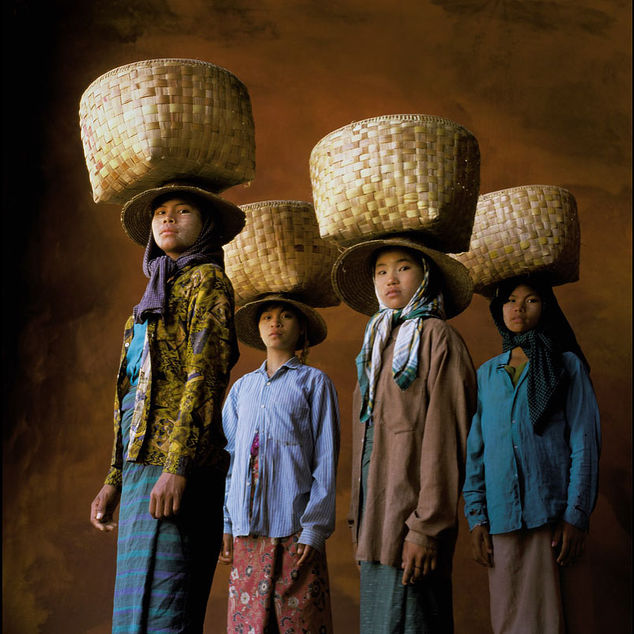

Günter Pfannmüller and Wilhelm Klein, among the earliest Western journalists allowed to travel widely in Burma, will attend. In researching the seminal “Insights” guidebook in the 1980s, they created a portable studio, making bewitching medium-format portraits of people from every corner of the country.

Mounting these ever-expanding programs has become a major challenge to Mr. Loviny and a small staff of volunteers working with an annual budget of about $75,000. Launched in 2008 under the auspices of the Institut Français, the festival is now run by PhotoDoc, a Burmese nonprofit association of documentary photographers.

In the early days, constraints on free speech and the press prompted cat-and-mouse games with the censor. Burma’s transition to democracy has brought uneven improvement in press freedom and greater scope to show photojournalism. Aung San Suu Kyi has been a regular participant and patron, while companies such as the bank KBZ and the local office of Canon have been big supporters. Festival topics have included environmental and human-rights issues, including deforestation, drug abuse and human trafficking.

Greater freedom and a growing economy have led to a golden age for the media and photojournalism in Burma. “Over the years, we’ve trained over 600 people,” Mr. Loviny says proudly, noting that many have gone on to successful photography careers.

Minzayar Oo was completing his medical studies before training at one workshop. He has since become a darling of international news organizations and among Asia’s most dynamic photographers, mounting powerful exposés of Burma’s nefarious jade-mining industry and the brutal ethnic violence against the country’s Rohingya Muslims. Mr. Minzayar won the festival’s grand prize last year, which included a trip to Amsterdam for the World Press Photo Awards.

Another previous winner, Mayco Naing, studied in France. Now a celebrated commercial photographer with her own studio, she described how dismal prospects were before the festival. Schools were shuttered by the military. Deprived of access to education, she says she worked for nine years in a local studio, saving to buy her first camera.

“When I got it, I was amazed. All of a sudden, I could explore myself.” She returns to the Yangon Photo Festival each year to help train other fledgling photographers. “Now, in Burma,” she notes with enthusiasm, “there are limitless possibilities.”

- Previous Japan’s Aso says wants to discuss rules for free trade with U.S.

- Next Syrian Troops Retake Palmyra From Islamic State