Batik – Common language of Diplomacy in South East Asia

Batik’s role in Singapore’s diplomacy

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong and his Malaysian counterpart Anwar Ibrahim, along with the delegations from Singapore and Malaysia, were dressed in batik at the 12th Singapore-Malaysia Leaders’ Retreat on Dec 4.

SINGAPORE – The usual dark suits of diplomacy gave way to pattern and colour when Singapore’s and Malaysia’s political leaders

met on Dec 4 for their annual retreat

Delegations from both sides came dressed in regional textiles, including a wide variety of batik, for the highest-level meeting between the two nations.

At a press conference after the meeting, both prime ministers affirmed positive ties, with PM Lawrence Wong emphasising a “constructive spirit” and mutual respect, while Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim said “there’s no hostility” over the longstanding issue of water.

More than their words, their choice of dress also represented regional solidarity and cultural connection between the two countries, experts said.

This was the 12th edition of the meeting. Over the last decade, the countries’ leaders have mostly appeared in Western-style suits at the meet’s press conference, except in 2023 when Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong, then prime minister, was dressed in batik alongside Mr Anwar in their first retreat together

.

Wearing batik is not just about fashion and trends, said Dr Azhar Ibrahim, a senior lecturer at the Department of Malay Studies at the National University of Singapore.

It communicates familiarity and understanding, and represents an alignment with the cultural aesthetics of the wider Nusantara, he said. Nusantara is an old Javanese term used to refer to both the Indonesian archipelago and the wider Malay archipelago.

Top stories

Swipe. Select. Stay informed.

Singapore

Woman arrested after graffiti found on walls, vehicles at Salvation Army premises in Bukit Timah

Singapore

Strong bids for plum state land plots in S’pore neighbourhoods slated for major urban renewal

Singapore

Man and teenager arrested for allegedly snatching cash from an elderly man

Asia

Thailand says Hindu statue removed to control border area

Asia

China social media thrashes one-child policy after population control czar dies

Asia

China urges travel agencies to cut Japan-bound visitors by 40%, say sources

Life

Merry Christmas in verse: Singapore poets on taxes and the holidays

“Using a ‘batik cultural universe’ as part of our diplomacy is like a common language, in print and style,” he added.

“It is a gesture of cultural camaraderie and a point where we can come together, despite differences.”

The textile art form is usually defined by the use of resist-dyeing techniques to mark out patterns using a substance, usually wax, before the cloth is dyed. This creates patterns of dyed and undyed cloth, often with many layers of colour.

At the recent meeting, PM Wong appeared to be wearing tenun, a different textile common in the region, said Ms Oniatta Effendi, founder of batik retailer Baju by Oniatta and Galeri Tokokita.

Museum docent and storyteller Hafiz Rashid concurred, adding that Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan was wearing a batik piece with floral and bird motifs.

Deputy Prime Minister Gan Kim Yong’s batik shirt carried a motif known as tambal – a pattern representing protection, healing and restoration, said Ms Oniatta.

The textiles they chose “gravitate towards safe and elegant patterns, florals and geometrics, and classic weaves”, she added.

“These are garments that do not carry heavy cosmological or power-laden meanings. The message they send is one of respect, cultural literacy and regional awareness rather than authority through motif.”

On the Malaysian side, leaders appeared to be in pieces from Malaysian batik producers in support of their domestic industry, she noted.

But batik is not always politically neutral. Historically, its associated patterns and motifs have been intertwined with power, wealth and politics.

Mr Hafiz said that in the past, textiles across South-east Asian societies were more than garments – they were a form of portable wealth and often used as informal currency in lieu of cash.

Ms Oniatta said that in Java, Indonesia’s largest island and home of its largest ethnic group, the Javanese, certain motifs were once reserved for royalty, so the cloth itself carried authority and status.

One example of this is the “parang” motif, comprising intertwined S-shapes that repeat across the cloth, which was once reserved for royalty and used in some instances to denote rank.

Dr Azhar said this system of codes and taboos is no longer in practice except in court ceremonies, but the significance has shifted to the political arena.

For example, former Indonesian president Joko Widodo used batik on various occasions to communicate power dynamics to his audience, he noted.

Former Indonesian president Joko Widodo used batik on various occasions to communicate power dynamics to his audience.

ST PHOTO: ARIFFIN JAMAR

In the modern era, it has also become a tool of diplomacy.

Post-World War II, Indonesian, Malaysian and Singaporean leaders adopted their own styles of dress, noted Dr Azhar.

In Indonesia, former president Sukarno was often seen in military-style clothing, while Malaysian leaders like Tun Abdul Razak would commonly wear a safari-cut shirt and jacket.

Singapore’s leaders were often seen in a white shirt with or without a jacket. But today, batik is worn at official functions and regional meetings, and at official and public initiatives, he said.

“The batik cultural universe is essentially a new phenomenon, in the era of nation-states building and affiliating their identities.”

NUS cultural geographer T.C. Chang said batik has been worn at regional and bilateral summits beyond the Singapore-Malaysia Leaders’ Retreat.

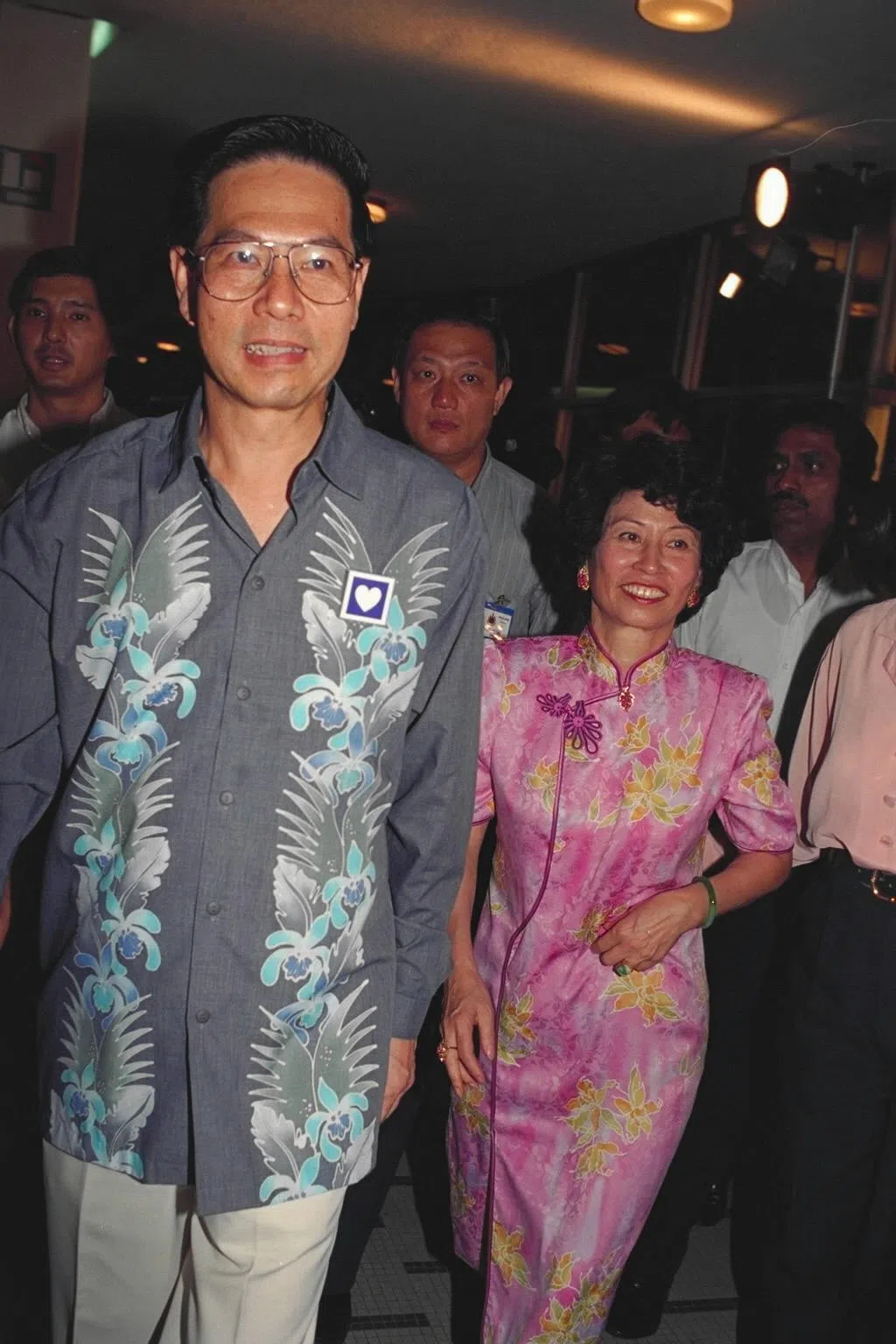

In 1994, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Bogor, Indonesia, leaders from the grouping’s 21 economies, including then US President Bill Clinton, Indonesian President Suharto, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and Singapore Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, were pictured wearing the textile.

World leaders at the 1994 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Bogor, Indonesia, were dressed in batik.

PHOTO: ST FILE

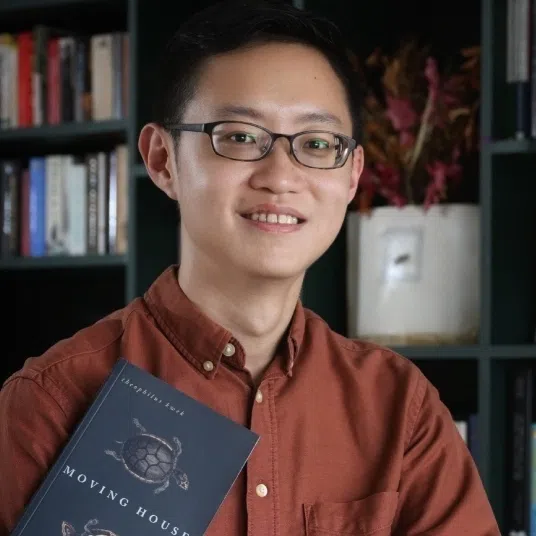

In Singapore, politicians like former president Ong Teng Cheong were pioneers in wearing the fabric, noted Prof Chang.

From the late 1980s, when he was Deputy Prime Minister and NTUC secretary-general, Mr Ong wore orchid-print shirts on many occasions, including National Day celebrations when he later became president.

Former president Ong Teng Cheong, then 57, celebrating his presidential election victory in 1993. With him was his wife Ling Siew May.

PHOTO: ST FILE

When used in the region, batik has become a sign of respect and understanding.

Dr Azhar said: “When our leaders meet their counterparts from Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei, it says, ‘I’m also familiar with your culture and aesthetics.’”

Singapore’s connection to batik remains a relational one, Ms Oniatta noted.

“We do not have the craft lineage; we do not have the land, the workshops or the communities of makers.

“But many of us carry diasporic roots from the archipelago, and batik sits in our lived memory.”

To her, when Singapore’s leaders wear the fabric, it signals an understanding of the heritage that shaped the region and that Singapore chooses to carry these relationships with respect.

“On a leader or an everyday person, batik becomes a message of cultural literacy, dignity and regional belonging.”

- Previous Thailand removes Hindu statue to control border area

- Next South Korean Hanwha Company’s Philly Shipyard can build nuclear submarine for U.S. Navy