Trump Places Tall Order on Trade Vow to put ‘America first’ complicated by thicket of international rules, prospects of unintended consequences

For President Donald Trump, quitting the already moribund Trans-Pacific Partnership may be the easiest part of his pledge to remake global trade relationships and protect jobs. His vows to confront China and renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement will be harder to fulfil.

Upending existing trade rules risks hurting U.S. firms that depend on sales to Canada, China and Mexico, the top three buyers of U.S. goods and services. Moreover, global trade is anchored in regulations layered on since the end of the World War II, making it difficult to change terms without setting off a domino effect of unintended consequences. That will likely complicate the Trump administration’s efforts to wrest economic concessions from existing trade partners.

“I don’t think they have a realistic sense of what it takes,” said Douglas Irwin, a Dartmouth College professor and historian of U.S. trade policy, referring to Trump administration officials. “It’s going to take time and be very complicated, with the risk being making sure that what you do is not completely disruptive to the U.S. economy.”

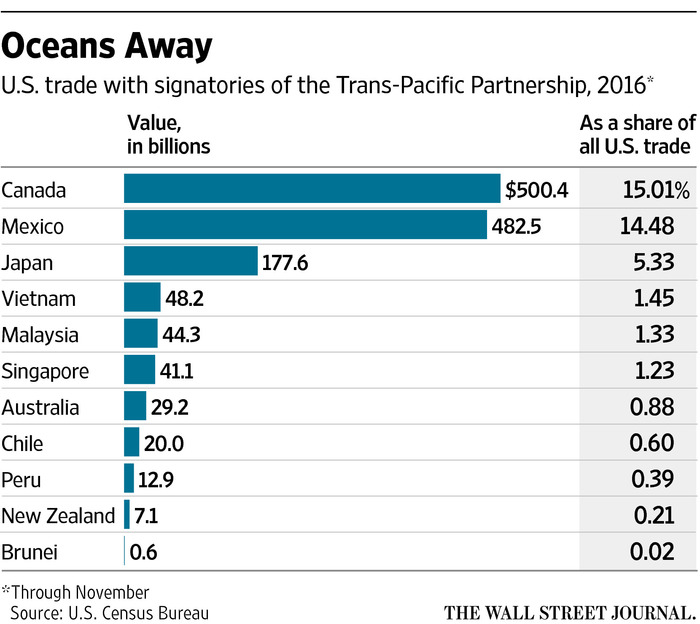

Mr. Trump formally quit the 12-member TPP on Monday, killing a proposed trade agreement the Obama administration had already abandoned hope of getting ratified in Congress. During his campaign Mr. Trump decried the pact as an emblem of how U.S.-negotiated trade deals benefit low-wage nations in the developing world at the expense of U.S. manufacturing.

For the new president, the next step appears to be meeting leaders of Canada and Mexico and kicking off a high-priority renegotiation of Nafta, the two-decade-old trade agreement that became a center of criticism in the 2016 campaign.

“Nafta is obviously first up, and that will be their trial,” said Gary Hufbauer, senior trade expert at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, which backs trade liberalization. “It will be a while before you have this template that you’re then going to apply to other countries.”

Mr. Trump made it clear in Monday’s withdrawal from the TPP that he prefers negotiating trade deals with one country at a time. Supporters of multinational deals say they make it easier to raise labor and other standards, and that larger trading areas can attract reluctant countries to enter—a big reason why Japan, long protective of its agriculture and retail sectors, agreed to open them to join TPP.

Many conservatives prefer bilateral pacts out of concern that multilateral deals can reduce the sovereignty of individual states. Mr. Trump’s aides have also suggested they see a negotiating advantage in bringing maximum leverage to bear on one partner at a time.

Republican lawmakers appear to have accepted Mr. Trump’s bilateral approach, a clear shift from Mr. Obama’s focus on broad regional talks that sought to achieve overlapping economic gains among the countries involved.

Mr. Hufbauer said it was even possible that what we now know as Nafta could devolve into a pair of bilateral deals, one with Mexico and another with Canada.

Mr. Trump and his advisers have also signaled they want to change the rules of origin for cars and perhaps other industries and establish rules that could punish countries blamed for manipulating their currencies. They also say they want to address taxes applied at the border—including Mexico’s value-added tax, or VAT—that they say tilt the balance against American manufacturers.

Each of those goals could generate controversy within the U.S. or more broadly in the North American bloc. A fight between Mexico and Japan over rules of origin for cars, which dictate where parts can be sourced, almost stopped the TPP in its tracks in 2015.

Currency manipulation divided U.S. lawmakers that year and nearly sank trade legislation that gave Mr. Obama—and now Mr. Trump—greater authority to enact deals. Disagreements over taxes at the border could bring the Trump administration to a clash with the World Trade Organization, lawyers say.

Even if the negotiations with Ottawa and Mexico City go quickly—as fast as, say, the speedy U.S. trade talks with Australia in 2003-2004—the new Nafta would barely emerge in time for the 2018 congressional elections.

Mr. Trump could try to apply new Nafta provisions to renegotiating an existing deal with South Korea, trade lawyers say, to new bilateral pacts with Asian countries such as Japan and Vietnam, or even to the U.K., which is seeking to leave the European Union.

To help navigate the potential crosscurrents, Mr. Trump is establishing a team of trade advisers steeped in international policy and Chinese business affairs.

They include Wilbur Ross, who was approved as commerce secretary by a Senate committee Tuesday, and his nominee for U.S. Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, a high-powered trade lawyer whose nomination has been welcomed by members of both parties on Capitol Hill.

Some analysts following Mr. Trump’s policy say the administration’s tough stance toward China and other major exporters could help wring some economic concessions or even lead to new deals.

Still, given the overwhelming backlash against trade agreements that brought Mr. Trump to power in 2016, the new president is likely to face political opposition to major deals that don’t meet the often disparate goals of domestic lawmakers, regardless of the international rationale for the agreements.

He will have one advantage: So-called fast-track authority, special trade powers Congress passed under Barack Obama that guarantee a timely vote on trade agreements, with no chance for amendments or procedural delays.

More broadly, the TPP withdrawal symbolizes a U.S. shift away from promoting free-trade blocs as a path to growth. A one-paragraph “America First Trade Policy” now inhabits the website of the U.S. Trade Representative. “USTR is working to reshape the landscape of trade policy to work for all Americans,” it says.

To keep jobs in the U.S., Mr. Trump and others have floated ideas that include ripping up existing trade deals like Nafta, erecting trade barriers, and prioritizing bilateral deals with individual nations over multilateral accords with trade blocs—a strategy adopted by the administration of George W. Bush.

The true test of how effective Mr. Trump can be in remaking U.S. trade will come when the administration takes on the economies it accuses most of taking U.S. jobs: China and Mexico. Together they account for more than $1 trillion in U.S. merchandise trade, or 30% of total U.S. imports and exports.

Mr. Trump has threatened a 45% tariff on Chinese goods unless the country stops practices such as subsidizing steel. While Mr. Trump has leeway to raise tariffs, such an across-the-board tariff could put the U.S. in violation of WTO rules, opening up the U.S. to retaliatory measures from China and other nations.

Mr. Trump also vowed to declare China a “currency manipulator,” referring to Chinese policies in past years that kept the yuan weak. That designation would allow the U.S. to hit China with more tariffs. But the administration may have trouble making the case, since China has recently sought to prevent its currency from weakening too much.

‘This is the kind of minefield that Trump is standing in the center of. You can’t step in any direction without setting off a chain reaction.’

Tariffs could also trigger a trade war with the world’s No. 2 economy. That would affect U.S. firms doing business in China and hurt U.S. allies, such as South Korea and Japan, that supply China with many components used in its exports. Such an outcome could be a blow to U.S. security interests in the region.

Mr. Trump’s meeting with leaders of Canada and Mexico may shed light on the changes he will seeking to Nafta. To get concessions from those countries—the No. 1 and No. 3 U.S. trade partners—the U.S. must have something to offer. For example, the Obama administration, which also criticized Nafta, sought to upgrade some aspects of the deal in the TPP talks, which included Mexico and Canada.

If the U.S. scraps Nafta, trade with Mexico and Canada would revert to WTO rules, which also tend to promote open trade. The 0% tariffs on cars under Nafta, for example, would only be allowed to rise to 2.5% under WTO rules.

“This is the kind of minefield that Trump is standing in the center of,” said Matt Gold, a Fordham University adjunct law professor and former deputy assistant U.S. Trade Representative. “You can’t step in any direction without setting off a chain reaction.”

Write to John Lyons at john.lyons@wsj.com and William Mauldin at william.mauldin@wsj.com

- Previous Trump expected to sign executive orders on immigration

- Next No more visits by Dalai Lama, Mongolia promises to China