Entire World gets 6% loans from China at $5 trillion

China’s loans to rest of the world worth US$5 trillion, 6 per cent of global economy, new study reveals

- The world’s debt to China grew tenfold between 2000 and 2017, from US$500 billion to US$5 trillion, with 80 per cent of emerging nations receiving Chinese funds

- Kiel Institute estimates that 50 per cent of Chinese overseas funding is outside data captured by World Bank and IMF, raising concerns over transparency

The world’s debt to China grew tenfold between 2000 and 2017, according to new estimates from a German think tank, at a time when there are growing concerns about Beijing’s influence over global finance.

As of 2018, the world owed more than US$5 trillion worth of debt to the government of China, or around 6 per cent of global economic output, according to a report published by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy last week.

This is a huge increase from the US$500 billion owed in the early 2000s, which was around 1 per cent of global economic output.

Analysts have long argued that China has not been consistently transparent with its lending to foreign countries, in particular, low income countries with little economic clout.

The nature of Chinese overseas lending means that many are outside the international banking system. While 85 per cent are denominated in US dollars, the loans are often issued by Chinese banks to Chinese contractors overseas to avoid direct loan disbursement to debtor country governments, which are considered to have high default risks.

This means there is no cross-border bank claim to report to the Bank of International Settlements, which acts as the key counterparty to central banks in financial transactions. As a result, many Chinese loans to foreign countries are not wholly captured by official debt statistics tracked by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

The Kiel Institute, therefore, estimated that the IMF and World Bank were only capturing half of China’s total foreign lending.

“Around 50 per cent of China’s international lending to developing and emerging countries is not included in official statistics. They are not recorded by multilateral surveillance institutions such as the IMF or the Paris Club, by rating agencies, nor by private data providers,” reads the report.

Alongside the opacity of China’s lending, the Kiel institute also said that its overseas lending has been growing exponentially. The research shows that 80 per cent of emerging and developing countries had received official Chinese grants or loans by 2017.

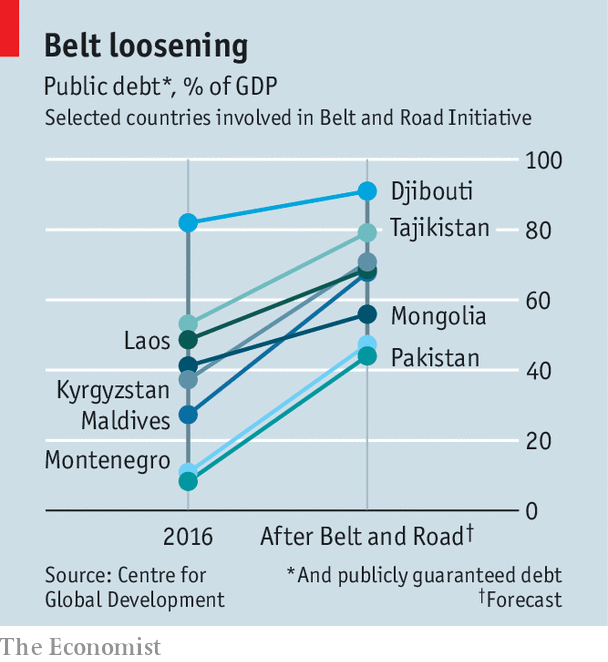

For the top 50 recipients of Chinese direct lending, the nations’ indebtedness as a portion of gross domestic product (GDP) increased to more than 16 per cent in 2017. Djibouti, Tonga, the Maldives, the Republic of Congo and Kyrgyzstan are the top five borrowers of Chinese state funds as a share of GDP, said Kiel Institute analysts.

The report estimated that developing and emerging market nations owe a total of US$380 billion to China. By contrast, they owe US$246 billion to the Paris Club, a group of 22 mostly Western, developed countries, that includes Germany, Japan, Russia and the United States.

The US government has been critical of China’s overseas investment, including the Belt and Road Initiative, the cornerstone of President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, which has seen hundreds billions of dollars disbursed for infrastructure projects linking Asia with the West.

Former Defence Secretary James Mattis said of the Belt and Road in 2017: “In a globalised world, there are many belts and many roads. And no one nation should put itself into a position of dictating ‘one belt, one road’.”

Others have argued that Beijing has intentionally extended excessive, expensive credit to another country in a bid to extract economic or political concessions, with the term “debt-trap diplomacy” commonly used in reference to Belt and Road by its critics.

China has denied that it was saddling emerging countries with unsustainable debts but has since said it would improve transparency and regulations in Belt and Road projects. Beijing has, however, yet to officially publish any data on its overseas lending.

The Kiel Institute report suggested that poor disclosure levels is problematic because China often lends to countries that are experiencing political and economic crises, such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and Iran, raising questions of debt sustainability and raising suspicions over what the Chinese agenda is in lending to these nations.

The new president of World Bank David Malpass, a former undersecretary with US Treasury and economic adviser to US President Donald Trump, has also criticised China’s efforts to fund large scale infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road label, saying the state-driven plan often leaves countries with “excessive debt and poor-quality projects”.

In April this year, after becoming World Bank president, Malpass said China needed to be more transparent with its lending to emerging economies. Referring directly to China, Malpass said: “Debt is something that helps economies grow, but if it’s not done in a transparent way, with good outcome from the build-up of debt, then you end up having it be a drag on economies. And history is full of those situations where too much debt dragged down economies.”

- Previous Ages old Turkish-Greek animosity gets new point conflict. This time over drilling for gas

- Next China demands US to cancel $2.2bn arms sale to Taiwan