Afghanistan Struggles to Access China’s New Silk Road

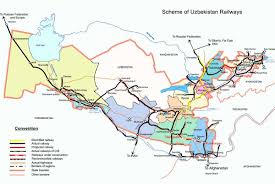

MAZAR-E-SHARIF, Afghanistan—A new railway between China and Afghanistan, part of Beijing’s Silk Road initiative to promote regional trade, has run into roadblocks in Uzbekistan, apparently over fears that it could also benefit terrorists.

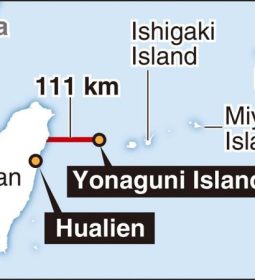

The first freight train on the Sino-Afghan Special Transportation Railway departed the Yangtze River port of Nantong on Aug. 25 and arrived in the Afghan river port of Hairatan two weeks later. Chinese state media said the cargo link would boost economic cooperation as the ancient caravan routes once did.

But the trains loaded with Chinese electrical supplies, clothing and other goods rattling in are returning from Afghanistan empty.

Despite diplomatic efforts by Afghan officials, Uzbekistan is refusing to allow Afghan goods to transit its territory on to Kazakhstan and China, Afghan and foreign officials say. The reason, they say is that the Uzbek government worries the trains could be used to smuggle narcotics and precious stones, which fuel criminal and terrorist networks in the region.

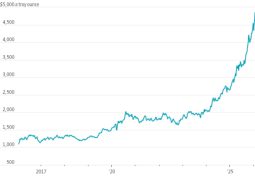

Afghanistan supplies most of the world’s opium, made from poppies, and about a quarter of that is trafficked to global markets through Central Asia. The crop is mostly grown in insurgent-held areas and is a major source of revenue for the Taliban and other groups. Production rose more than 40% in Afghanistan last year, according to the United Nations.

The region is experiencing a rise in militant activity and Afghanistan is a hub for groups like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a U.S.-designated terrorist organization linked to Islamic State. Such groups could benefit from narcotics smuggling in Central Asia.

The Afghan government says it is working to reassure its northern neighbors that the new railway won’t become a conduit for narcotics.

“We have agreed to start working on a transit agreement” with Uzbekistan, Afghan Finance Minister Eklil Hakimi said. “The problem will be resolved.”

Officials at the Uzbek transport ministry, railway and embassy in Kabul didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The Chinese government didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.

For now, China is low on the list of Afghanistan trading partners. Afghan exports go mostly to Pakistan, India and Iran, according to World Bank data. Even Russia’s 3% share of Afghanistan’s exports is bigger.

The Afghan government hoped the new railway would draw in investors by offering a cheap means for exporting natural resources. Investment has been at a standstill due to worsening security and almost nonexistent infrastructure.

Last year officials from China’s trade-promotion agency told their Afghan counterparts that China was eager to import more agricultural goods such as saffron, according to the agency’s report on the meeting.

Chinese buyers also are major consumers of precious stones like lapis, found in northeastern Badakhshan province, close to the railway port.

State-owned China Metallurgical Group Corp. has secured a $3 billion, 30-year concession to a huge copper deposit south of Kabul, along with oil and gas blocks in the north, but these projects are largely at a standstill.

“Afghanistan is rich in natural resources that aren’t touched,” said Shir Ahmad Sepahizada, local director of industry and commerce in Balkh province, the railway’s Afghan terminus. He lamented the lopsided trade. “Many countries don’t have raw materials but we do.”

Others suggest the relatively small market isn’t a priority for Beijing.

“If the demand in China to import goods from Afghanistan were big enough, China would talk to Uzbekistan to address this issue,” says Zhu Yongbiao, a Central Asian expert at Lanzhou University in China.

Other countries in the region share Uzbekistan’s concerns about terrorism, but also say that promoting economic opportunities and integration is the best defense.

“Afghanistan has good potential for providing precious stones and metals, and we are interested in this,” said Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Omirtay Bitimov. “Improving the economic situation will help decrease the threat from terrorism and drug production.”

The desolate border town of Hairatan, which sits by the Amu Darya river, was once a bustling hub for convoys transporting materials for the U.S.-led military coalition.

For now, Afghan businesses use the new China route as an alternative to importing goods through Pakistan, a route that took over a month and often experienced long delays as a result of the strained relationship between the two countries.

But weakening economic conditions in Afghanistan are eroding demand. Yama Absar, who imports electronic goods from China, has seen his business plummet.

“The Afghan government—previous and current governments—is unable to fulfill basic duties,” he said. “As an ordinary citizen, I am not happy.”

—Thomas Grove in Moscow and Lilian Lin in Beijing and Trefor Moss in Shanghai contributed to this article.

Write to Jessica Donati at Jessica.Donati@wsj.com

- Previous Trade turnover between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan reaches $ 2bn

- Next PM warns of “fake news” peddled by parties bent on toppling gov’t