After Sri Lanka attacks, Muslims face boycotts and violence

MINUWANGODA, Sri Lanka — The New Fawz Hotel was a bustling institution in this small Sri Lankan town, beckoning diners with its huge red neon sign and hot plates of chicken and rice available day and night. But after the Easter Sunday terrorist attacks, customers stopped showing up.

Things got worse. In May, men on motorbikes arrived wielding sticks, their faces covered with helmets. They smashed the restaurant’s glass windows as a huge crowd gathered, then surged into the premises and destroyed everything inside. M. M. Mohomed Indhas, the proprietor, fled out the back, afraid for his life.

“We were born here, this is my hometown,” said Indhas, 52, standing outside the wrecked shell of the restaurant. “Now we wonder whether there is a future in Sri Lanka.”

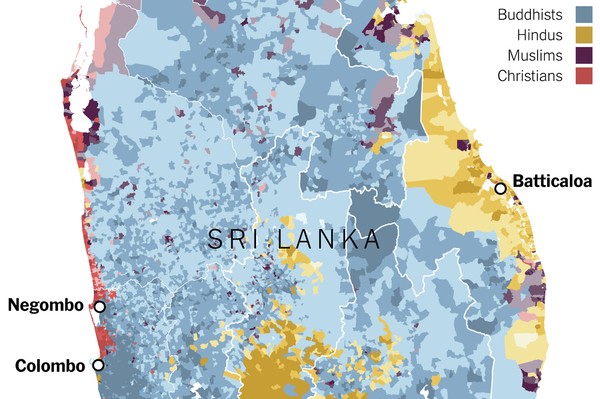

Indhas is a Sri Lankan Muslim, a religious minority in this predominantly Buddhist country. In the wake of the devastating April attacks — carried out by local Islamist extremists — the entire community braced itself for retaliation.

Now those reprisals have arrived. Muslim-owned businesses are facing informal boycotts. Anti-Muslim riots broke out in two provinces in May, damaging hundreds of businesses, homes and mosques and leaving one person dead. Nine Muslim ministers resigned in June, partly because they feared that if they did not, more violence was imminent.

Experts worry that Sri Lanka, a multiethnic and multireligious democracy whose bloody civil war ended in 2009, is poised for a new outbreak of tensions. This time the divisions are emerging along religious lines, rather than the long-standing ethnic cleavage between Sinhalese and Tamils.

Even before the Easter attacks, Muslims, who make up about 10 percent of the population, had faced discriminatory rhetoric and sporadic violence, particularly with the rise of hard-line Buddhist nationalist groups after the end of the civil war.

But the current climate marks a perilous turn. Last month, one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent Buddhist monks called for a boycott of Muslim-owned businesses and appeared to condone violence. “Don’t go to their shops or eat their food,” said Warakagoda Sri Gnanarathana Thero, endorsing a bigoted slur that Muslims are trying to sterilize people. “Buddhists must protect themselves.”

The country’s finance minister shot back, saying that such statements were a perversion of the faith. “True Buddhists must unite NOW against the Talibanization of our great philosophy of peace & love of all beings,” wrote Mangala Samaraweera on Twitter.

After the April attacks, which killed more than 260 people, conspiracy theories have run rampant. A Muslim gynecologist was recently accused by a nationalist newspaper, without providing any evidence, of sterilizing thousands of Sinhalese Buddhist women against their will. The unsubstantiated allegations dominated media coverage for weeks.

Some observers say that the anti-Muslim rhetoric serves a political purpose: to polarize the electorate ahead of presidential elections later this year. Opposition parties “want to keep this pot boiling,” said Rauff Hakeem, leader of the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress, a political party that is part of the current governing coalition.

Hakeem was one of the nine Muslim ministers who resigned in June. (Two have since been reinstated.) He said that the group made the decision to step down as a response to “a presupposition of links to terrorism” that was “demonizing the entire community.”

On May 13, packs of men on motorcycles began roaming towns in areas north of the capital, Colombo. Police did little to stop them from targeting Muslim businesses and homes, witnesses said, whether out of fear, complicity or a lack of manpower. A national police spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

In Minuwangoda, part of a district of 177,000 people — just 3 percent of them Muslim — northeast of Colombo, the rioters came prepared. After mobs attacked the area near the New Fawz Hotel, they traveled five miles down the road to where Ali Jisthy’s family had completed a new pasta factory, the largest of its kind in Sri Lanka. A crowd of about 200 people pushed down the large aluminum sliding doors leading to the facility. Once inside, they set tires on fire, Jisthy said.

Neither the police nor the fire department took any action, but two hours after the fire began, the army showed up. The blaze burned until 1 p.m. the following day. The three-story-high imported Italian pasta machine, which had taken nine months to build, was gutted. The cost of the damage and lost sales is about $4 million, Jisthy estimates.

“Purely because of your faith you’re being attacked,” said Jisthy, 23. “That’s something I’ve never experienced before.”

At the police station in Minuwangoda, chief inspector L.B. Aberatha said that 70 people had been arrested for the rioting and nearly all were granted bail. He said he could not fathom why the rioters had picked the town, nor state whether the violence had been planned. In total, 76 businesses and homes and one mosque were damaged.

Residents of towns farther north described a similar phenomenon that night: men arriving on motorbikes bent on destruction. In Ihala Kottaramulla, a Muslim enclave, Mohamed Sali Fausul Ameer, a 49-year-old carpenter, told his wife and four children to turn off the lights and lock the door while he went outside.

As they huddled in the back, they heard rioters attacking a neighboring house then breaking down their own gate and trying to set their car on fire. Then the crowd was running away. Ameer’s wife, Fatima Jiffriya, said she went outside and found her husband on the ground, bleeding from a deep cut to his neck. He later died.

The police “didn’t even help me take him to the hospital,” she said. “Now my life is completely ruined.”

Two people have been arrested for the killing, a local police officer said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly about the incident.

Back in Minuwangoda, Indhas said he hopes to reopen the New Fawz Hotel for business later this month and plans to use the costly repairs to make improvements. One significant thing will change, however: The sign reading “halal” in large red neon letters on the side of the restaurant will be removed. “It’s causing problems,” he said. “Sinhalese people won’t come.”

- Previous Hekmatiyar: Foreigners Trying To Monopolize The Peace Process

- Next Iran passes new nuclear deal limit, China blames US for crisis for this