Can Malaysia find a ‘third way’?

By Haris Hussian

September 9, 2019 @ 9:45am

KUALA LUMPUR: The Defence White Paper (DWP), which will map out the future direction of the Malaysian armed forces, is expected to be tabled in Parliament in November.

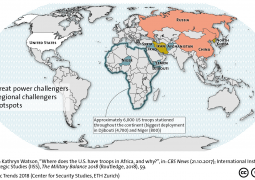

Set against the simmering tensions in the South China Sea, the upheaval in Hong Kong, China’s insistence on exerting its hegemony on a defiant Taiwan and the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, defining the future role of the armed forces looks to be a daunting task.

Deputy Defence Minister Liew Chin Tong was unequivocal in laying out the challenges in the coming decades, outlining our place in the “new” World Order and of the alliances that must be forged to maintain some semblance of leverage.

“It’s not going to be easy navigating this space,” Liew told the New Straits Times during a 40-minute sit-down at his office in Jalan Semarak here.

“In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and we had the Hat Yai Peace Accord, which marked the end of the communist insurgency in Malaysia.

“So we had two major, watershed events, both domestically and internationally.

“We have had 30 years of peace in Malaysia, and a relatively peaceful global scenario.

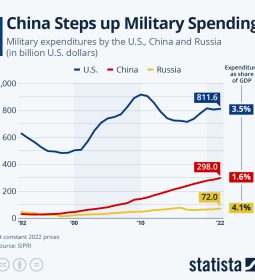

“I think now, we are entering a different era, in the sense that the US-China competition is going to be a long-term thing. It is going to be a competition that is not just about trade.”

Liew added that this would probably see the decoupling of China from the global supply chain of materials, strategic competition between nations jostling for regional dominance and the forging of new alliances, for instance, between Russia, China and Iran.

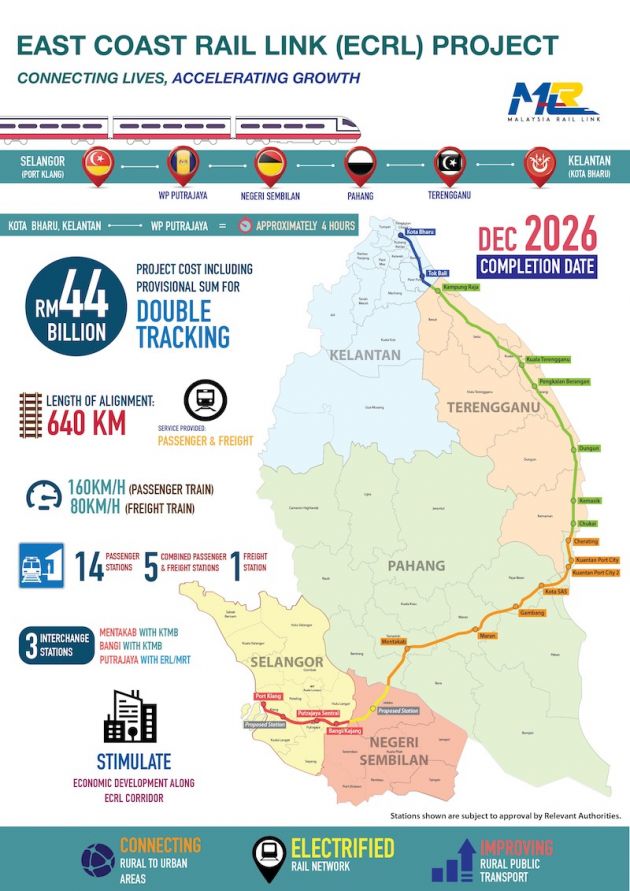

Observers said that China’s Belt and Road Initiative was the first shot across the bow in a “pre-emptive strike” against the US and the current world order.

They added that the US could have solved its trade dispute with China if it wanted to, but is now engaged in a “geopolitical contest”, with political imperatives being at the core of what appears to be a trade war between the two economic giants.

“Is this New World Order going to be the new Cold War? I don’t think so. I think it’s going to be more than that. It may not necessarily lead to a ‘hot’, or a shooting war, but it will be somewhere in between,” Liew said.

Already, traditional alliances are crumbling, with Turkey being a prime example.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) member, reeling from a major tectonic policy shift by the Trump administration, is gravitating closer to Moscow.

While still a member of the alliance, analysts say the 60-year strategic pact between Washington and Ankara is effectively over.

Since the July 15, 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, relations between the two countries have been strained to near-breaking point.

In the most recent spat, Ankara, a major contributor to the US F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter programme, was struck off Lockheed Martin’s global supply chain when it went ahead with the purchase of the advanced S-400 surface-to-air missile system from Russia, against Washington’s wishes.

A Boeing F/A-18C Hornet of the fighter/attack squadron VFA-192 ‘The World Famous Golden Dragons’ launches off the waist catapult of a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. In May, the United States deployed the carrier ‘Abraham Lincoln’ to the Persian Gulf in response to Iran’s threat to resume its nuclear development programme. It also despatched several nuclear-capable bombers to the region as a sign of resolve. FREEPIK PIC

Turkish defence firms stand to lose upwards of US$12 billion (RM50.2 billion) from the cancellation of the programme, while up to 30,000 jobs are at stake.

“I think what we are trying to do, what (Prime Minister Tun) Dr Mahathir (Mohamad) is trying to do, is to find a middle ground… especially vis-a-vis the US and China.

“Choosing a side has consequences; not choosing one also brings with it consequences. Can we find a third way?

“What the prime minister is trying to do is to find that space where ‘I’m not totally pro-US, and I also work with China quite a lot’.

“Finding that space is not going to be easy… but it is something that we need to do.”

Another potential flashpoint is the Middle East.

In the last few months, the region has teetered on the brink of war with the US accusing Iran of violating numerous conditions in the 2015 nuclear accord which both nations inked, but which the US reneged on in May last year.

Additionally, the US announced more crippling sanctions against Teheran.

Washington also authorised the forward deployment of the US Navy aircraft carrier, the USS Abraham Lincoln and its battle group, as a show of resolve.

It also pre-positioned other “first strike” assets — the B-52H Stratofortress and B-2 Spirit nuclear-capable bombers — to the Persian Gulf.

In response, Iran, in July, ditched two other commitments outlined in the nuclear deal — to keep its stockpile of enriched uranium below the stipulated 300kg, and to cap the purity of its uranium stocks to 3.67 per cent.

On Sept 5, President Hassan Rouhani announced that the restrictions on Iran’s nuclear research and development would be lifted, and repeated his threat that Teheran would take additional steps away from the 2015 agreement by Sept 6, including restarting the development of centrifuges to speed up the enrichment of uranium if Europe failed to provide a solution to the nuclear impasse.

Iran has been in talks with Britain, France and Germany in trying to salvage the deal that has been imploding since the US withdrawal.

“This is another difficult space in which we have to navigate.

“This, and Saudi Arabia and Iran. Where do the Islamic countries stand? Where do we stand?

“Can you not choose, by coming together, say under the non-aligned spirit, with other Muslim nations?

“We are looking for space, to not be tied down by the Iran-versus-Saudi tensions.

“Fortunately, Dr Mahathir is quite savvy… one possible option is a closer alignment with Pakistan and Turkey. Eventually, this may also include Bangladesh and Indonesia.”

Liew said another area that needs to be looked at is Malaysia’s place in the global context.

Shedding what he calls the “insular mentality” is essential in moving forward as a nation.

“Do we see ourselves as just a small nation or do we see ourselves as a nation that has the potential of punching way above our weight?

“Do we see ourselves as just the peninsula, and Sabah and Sarawak — very insular, inward-looking — or do we see ourselves as a maritime nation?”

He added that Malaysia’s geographical position puts it in a unique spot to shape the events and affect the dynamics within the region, and beyond.

“We have the two land masses… on one side, we have the Straits of Malacca, one of the most important sea lanes in the world.

“On the other, we have the South China Sea, arguably the most contentious piece of real estate in the world.

“And we are at the end of the Asia-Europe continent.

“When you see yourself in that context, you realise quickly that you are at the centre of a lot of things.

“How do we leverage our geography? How do we strategise? I think we need to get the nation into these kinds of conversations.

“Once you see yourself in relation to your geography, you’re no longer talking about Malay, Chinese or Indian. You need to be talking about Malaysia and the rest of the world.”

- Previous Haze in Malay Peninsula: Jakim calls on all mosques to hold Istisqa prayers for rain

- Next Elderly husband of 73-year-old Indian woman who gave birth to twins suffers stroke