China’s Banks Are Hiding More Than $2 Trillion in Loans

In 2014, the Chinese city of Haimen on the mouth of the Yangtze River set out to build a large apartment complex and turned to Bank of Nanjing Co. for about $29 million in financing.

The bank was happy to oblige but it didn’t call the money a loan, according to people familiar with the matter. It was added to Bank of Nanjing’s balance sheet as an “investment receivable,” a loosely regulated category of assets that allows bank officials to set aside little or nothing for potential losses.

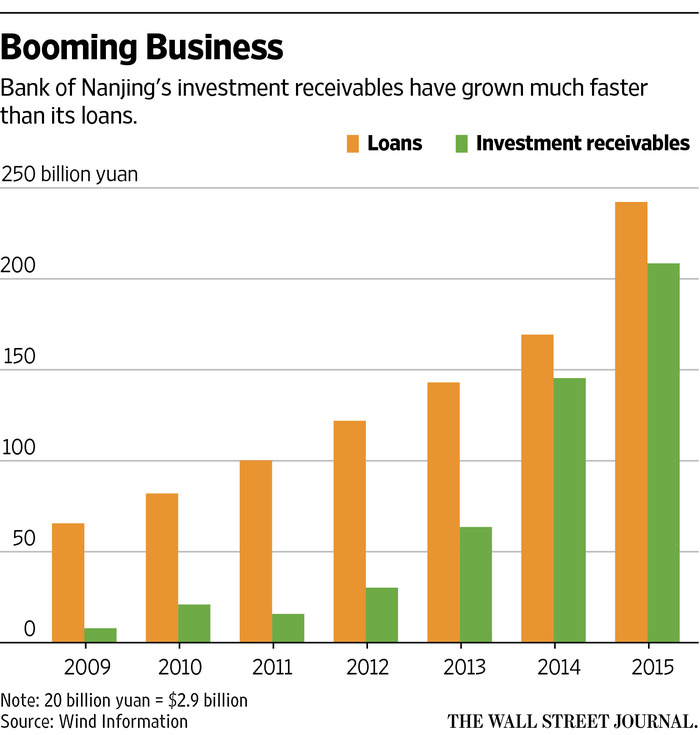

Bank officials aren’t shy about the accounting sleight of hand, which is rampant across China. The bank had about $39 billion in investment receivables in the third quarter, nearly as big as its loan portfolio, and profits have climbed by more than 20% a year.

As of June, 32 publicly traded Chinese banks had a total of $2 trillion in investment receivables as of June, up from $334 billion at the end of 2011, according to a tally by The Wall Street Journal of the latest available information from data provider Wind Information Co.

The investments are equivalent to 20% of the same banks’ total loans in dollar terms, up from 6% at the end of 2011. The 32 banks have about 70% of all the banking assets in China.

The surge shows how Chinese banks are trying to keep the credit spigot open to support the country’s slowing economy. Structuring financing deals as investments instead of loans frees up bank capital and makes it easier to extend loan deadlines or new credit to borrowers. The strategy has been especially popular at small and midsize banks, said executives and analysts.

The epidemic of investment receivables has created a parallel buildup of debt in addition to China’s rising official debt levels, now 2½ times gross domestic product. “The rapid growth in banks’ off-balance-sheet and investment activities, in essence, means hidden credit risks and could threaten financial safety,” said Shang Fulin,China’s top banking regulator, in an unusually blunt speech in September.

Economists at Swiss bank UBS AG estimate as much as $2.4 trillion (16.5 trillion yuan) was “missing” from the broadest measurement of credit disclosed by China’s central bank last year, up from $712 billion (4.9 trillion yuan) in 2014. The discrepancy is largely because Chinese commercial banks use so-called shadow lenders to mask loans as investments, the economists said.

In November, China’s top banking regulatory agency proposed rules that could force financial institutions like Bank of Nanjing to apply more-stringent accounting standards to investments that are essentially loans.

So far, though, authorities have been reluctant to come down too hard, fearing it could jolt the country’s financial system. In 2013, the People’s Bank of China set off a cash crunch by tightening liquidity in the interbank market where banks and other financial institutions borrow from each other.

The central bank was trying to rein in shadow lending but left some commercial banks and nonbank lenders in a desperate scramble for funding.

If Chinese banks were required to count their investment receivables as loans, the banks would need to raise as much as $212 billion in capital, estimates UBS analyst Jason Bedford. That is not far short of the $262 billion raised by all Chinese banks in 2015.

As a result, the analyst said, “we expect any capital impact [on banks] to be dragged out over years to avoid a shock to the system.”

Some banks are showing new signs of restraint. Investment receivables at 24 banks that have released third-quarter results totaled about $1.6 trillion, barely changed from June 30, according to the Journal’s tally.

Yet the advantages of the strategy remain hard for bankers to resist. Turning loans into investments has helped Chinese banks continue funding troubled customers, including property developers with too much inventory and deeply indebted financing companies set up by local governments.

Last year, nearly 90% of the loan-like investments created by Bank of Luoyang Co. and shadow lenders were used to finance real-estate developments, according to a June report by China Chengxin International Credit Rating Co., one of China’s top ratings firms.

Most of the projects were concentrated in Zhengzhou, a city that symbolizes China’s housing glut. Bank officials didn’t respond to requests for comment.

An early sign of trouble came with the 2014 default of a $538 million asset created by Evergrowing Bank Co., a small bank in Shandong province, to channel funds to an investment firm.

Evergrowing included the asset in its investment receivables, setting aside just 25% of risk-weighted capital against possible losses on the investment, according to analysts and the bank. If the asset had been counted as a loan, Evergrowing would have been required to set aside four times as much.

At first, the maneuver increased the bank’s capital and profits. But the default wiped out nearly 60% of the net income Evergrowing had earned in 2013.

Disguising loans as investments took off because of the government’s efforts to make it easier for banks to compete on interest rates. That has eaten away at profits banks make from the difference between what they charge on loans and pay on deposits.

Bank of Nanjing was started in 1996 and became a major player in China’s government-bond market by buying and selling such bonds. People familiar with the bank said the initial focus on trading and investing eventually hindered expansion, since rules limited the growth of its portfolio.

Getting around those limits was part of the impetus to increase investment receivables, the people close to Bank of Nanjing said. In 2013, the bank formed an asset-management firm called Xin Yuan Asset Management Co., which became the bank’s primary partner in packaging loans as investments.

Much of the money has flowed to projects like those in Haimen. In 2014, Bank of Nanjing gave $29 million to Haimen Development and Investment Co., the main financing company owned by the city.

Instead of a traditional loan to the financing company, Bank of Nanjing asked Xin Yuan to create a $29 million investment product with an annual yield of about 8.8%. The bank then pitched the investment to its own retail customers.

The sequence helped the bank get around several different lending restrictions. The city-owned financing company received a big infusion even though it is deeply in debt.

Haimen Development has more than 60 yuan in debts for every 100 yuan in assets it owns, according to a financial disclosure by the company. Last year, its operations were more than $100 million in the red, meaning it is kept afloat with government support.

The idea behind the apartment complex was to move farmers into the units as part of a broader move to cities across China. But jobs, schools and health-care services have lagged behind. Half the apartments were empty during a recent visit, and an open space with a playground was deserted.

An official at Haimen Development said the $29 million “will be fully paid off” and declined to comment further.

Bank of Nanjing said in a written statement that all its operations “meet legal and regulatory requirements.” The bank said it follows a “comprehensive risk-management” strategy while expanding its businesses.

Other projects funded the same way by the bank include an industrial park across the Yangtze River from the city of Nanjing. That project received $23 million in the form of an investment receivable, according to the people familiar with the matter and documents reviewed by the Journal.

While a new road leads to the industrial park and the area is filled with construction cranes, few businesses or factories seem to be moving in. The industrial park is an expansion of an industrial zone pocked with empty lots.

“The industrial park has been here for many years, but I’ve never seen much business here,” said Wu Haoyuan, a construction worker on a nearby building site.

From 2013 to 2015, assets at Bank of Nanjing nearly doubled, including the surge in investment receivables. In the first nine months of this year, profits jumped 23% from a year earlier. Soured loans total less than 1% of assets.

The bank has an ample capital cushion, based on its stated loan portfolio. But if all its shadow loans were treated as actual loans, the bank’s Tier 1 capital ratio could fall below the 6.7% required by regulators, according to the methodology used by Mr. Bedford, the UBS analyst. Tier 1 measures a bank’s highest-quality capital as a percentage of risk-weighted assets.

In June, ratings firm Standard & Poor’s downgraded its credit outlook on the bank to negative from stable, citing an eroded capital buffer following rapid expansion. S&P later withdrew its ratings at the bank’s request. The ratings firm declined to comment on Bank of Nanjing.

The lender isn’t worried about its funding for the apartment complex in Haimen or the industrial park in Nanjing, according to people close to the bank. The reason: Whether the projects make economic sense or not, bank officials expect to be repaid because of the projects’ government ties.

“All banks are trying to move [loans] off balance sheets,” said an official at Bank of Nanjing, nodding to a common belief in China that Beijing always will stand behind the country’s banks. “The only risk we have is sovereign risk.”

Write to Lingling Wei at lingling.wei@wsj.com

- Previous Asia’s Moral Duty to the Rohingya Being denied their basic human rights has left them stateless and suffering—and prone to radicalization.

- Next South Korean President Park Seen Likely to Be Voted Out