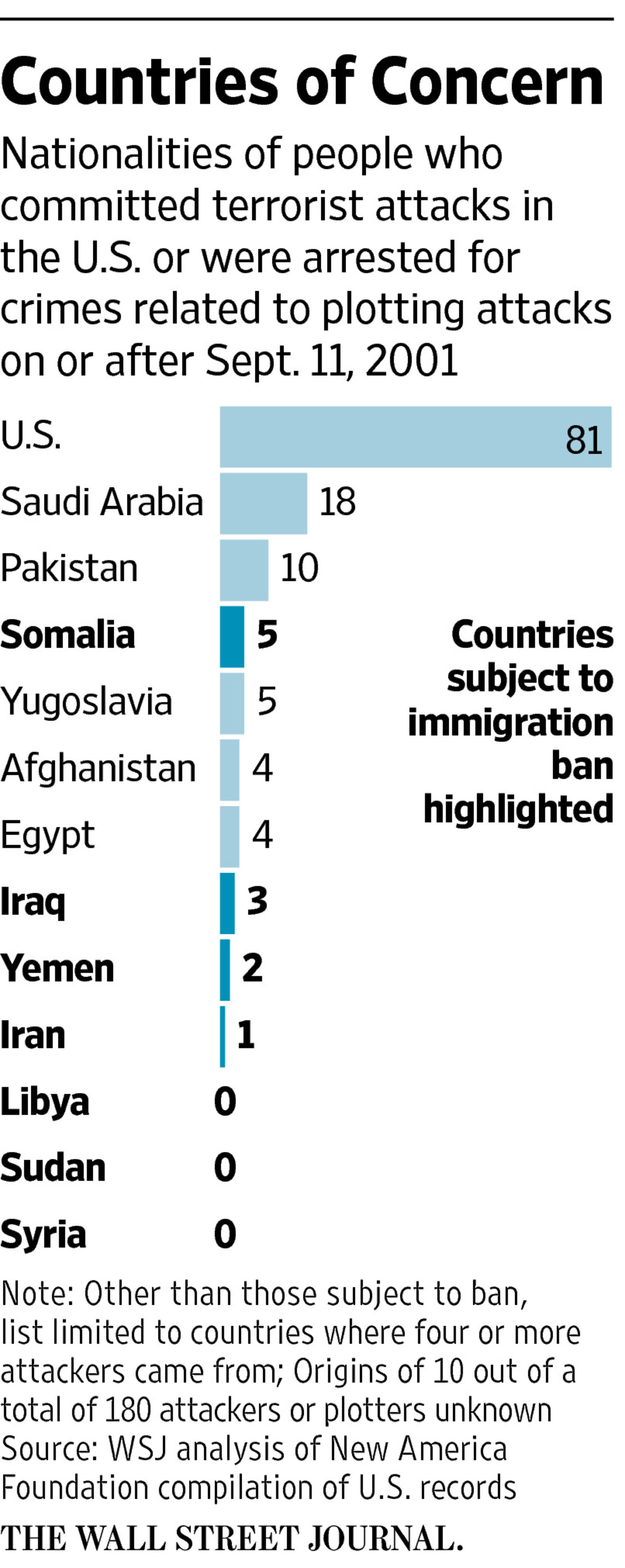

Countries Under U.S. Entry Ban Aren’t Main Sources of Terror Attacks

WASHINGTON—President Donald Trump’s e xecutive order to temporarily ban entry from seven Middle Eastern and African countries states that it is intended to “protect the American people from terrorist attacks by foreign nationals admitted to the United States.”

However, few of the dozens of plots in the U.S. during and after 2001 were attempted or carried out by suspects who came from the countries targeted under the ban.

Of 180 people charged with jihadist terrorism-related crimes or who died before being charged, 11 were identified as being from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Yemen, Sudan or Somalia, the countries specified in Mr. Trump’s order, according to an analysis of data on the attacks by The Wall Street Journal.

The Journal analyzed U.S. law enforcement records on terror-related plots and arrests that were compiled by the nonpartisan New America Foundation. The data include those charged with conducting attacks, killed while executing attacks, taking steps toward violence in the U.S., or materially supporting terrorism. It doesn’t include people charged with attempting to travel abroad for jihadist purposes, with no direct correlation to a U.S. attack.

The New America Foundation data also didn’t include the 19 Sept. 11 attackers. They were added as part of the Journal’s analysis of the data.

President Trump’s chief of staff, Reince Priebus said Sunday on Meet the Press that the seven countries were deemed countries of concern by Congress and the Obama administration.

The countries list originates from a bill Mr. Obama signed in 2015 that was originally introduced by Republican lawmakers, with some Democrats supporting it. The legislation grew out of concerns about citizens from a variety of countries becoming fighters for Islamic State or other groups in Iraq and Syria, then potentially visiting the U.S. The House version of the bill had 93 co-sponsors, about a third of whom were Democrats.

A federal program allows people from the U.K., France and about three dozen other nations to travel to the U.S. for business or vacation without a visa.

The 2015 law curtailed the program. That required anyone from the list of approved countries who has traveled to Iran, Iraq, Sudan and Syria to obtain a U.S. visa before entering the country. In 2016, the Department of Homeland Security added Libya, Somalia and Yemen to the list.

The data from the New America Foundation is similar to other estimates that have emerged since Mr. Trump signaled his immigration crackdown and that have been cited by those critical of Mr. Trump’s immigration ban, even if they think some changes are warranted.

“We have a lot of things that we need to build upon, some stuff we need to refine, some stuff we need to do better,“ said Ali Soufan, a former FBI agent who worked on high-profile terrorism cases and worked on some of the systems in place to vet travelers during the Bush administration. ”But we can’t be bulls in a China shop and say you’re not allowed in the U.S., period. Because that’s going to create a lot of animosity and that’s going to feed the ideology of many of the terrorist groups we’re concerned about.”

Approximately 85% of all suspects who took steps toward terrorist-related violence inside the U.S. since the Sept. 11 attacks were U.S. citizens or legal residents and about half were born U.S. citizens, New America Foundation officials calculated. Birthplaces couldn’t be definitively determined in 10 of the cases.

None of the major U.S. terrorist attacks or plots on or since Sept. 11, 2001, appear to have been carried out by people from the seven countries. The 19 men involved in the Sept. 11 attacks were from Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. The same is true of other prominent incidents since the Sept. 11 attacks.

In the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, Nidal Hassan, then a U.S. Army major who killed 13 and wounded 31, was born in the U.S.

The 2013 Boston marathon bombing that killed three and wounded hundreds more was carried out by brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, born in Russia and Krygystan respectively.

In the 2015 San Bernardino attack, Pakistan-born Tashfeen Malik and her American-born husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, killed more than a dozen co-workers and injured 21 more.

The 2016 Orlando, Fla., nightclub attack, killing 49 and wounding more than 50, was carried out by Omar Mateen, who was born in New York.

Several major U.S. plots that were thwarted over the years also didn’t involve people from the seven countries specified in Mr. Trump’s order.

British-national Richard Reid failed to detonate a shoe bomb in a Detroit-bound airliner 2001. American-born Jose Padilla was arrested in 2002 as he plotted to build and detonate a so-called dirty bomb with the goal of spreading radioactive material with conventional explosives. Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab is a Nigerian-born man who attempted unsuccessfully to blow up a jetliner with explosives placed in his underwear in 2009. A botched bombing of Times Square in 2010 was attempted by Pakistani national Faisal Shahzad.

All were convicted in those plots and are serving U.S. prison sentences.

Of the 11 terror suspects who did come from one of the seven countries targeted by Mr. Trump’s order, three were from Iraq, one was from Iran, two were from Yemen and five were from Somalia.

Two of the 11 were involved in acts of violence. Iranian native Mohammed Taheri-azar was convicted after authorities said he intentionally struck people with an SUV at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, injuring nine, in 2006. Somali Abdul Razak Ali Artan carried out a knife rampage at Ohio State University in 2016, injuring 11 before he was confronted and killed by a police officer.

Of the other suspects from the seven countries targeted by Mr. Trump, two of the 11 were convicted based on sting-style law enforcement operations. Several others were convicted after they declared their intent to back Islamic State causes or for unsuccessfully attempting to ally with Islamic State on attacks in the U.S.

In recent years, counterterrorism experts and law-enforcement officials have said that a greater danger is posed by homegrown extremism, which can feed on ideas emanating from the Middle East, than by radicalized immigrants physically coming to the U.S.

“It is no longer necessary to get a terrorist operative into the United States to recruit,” said FBI Director James Comey in testimony before a Senate committee in late 2015. “Terrorists, in ungoverned spaces, disseminate poisonous propaganda and training materials to attract troubled souls around the world to their cause. They encourage these individuals to travel, but if they can’t travel, they motivate them to act at home.”

Many advocates for refugee resettlement criticized Mr. Trump’s order, calling it misguided and an overreaction.

“This nation has a long and rich history of welcoming those who have sought refuge because of oppression or fear of death,“ said Cardinal Joseph Tobin of the Archdiocese of Newark in a statement. ”Even when such groups were met by irrational fear, prejudice and persecution, the signature benevolence of the United States of America eventually triumphed.”

In fiscal year 2016, the U.S. admitted approximately 85,000 refugees, including approximately 12,500 Syrians. Mr. Trump said the U.S. will admit 50,000 in fiscal year 2017, with a permanent freeze on Syrians. The entire program will be suspended for four months, and Mr. Trump moved to prioritize Christian refugees.

—Joe Palazzolo and Will Mauldin contributed to this article.

Write to Felicia Schwartz at Felicia.Schwartz@wsj.com and Ben Kesling at benjamin.kesling@wsj.com

- Previous Recent developments surrounding the South China Sea

- Next Who Hasn’t Trump Banned? People From Places Where He’s Done Business