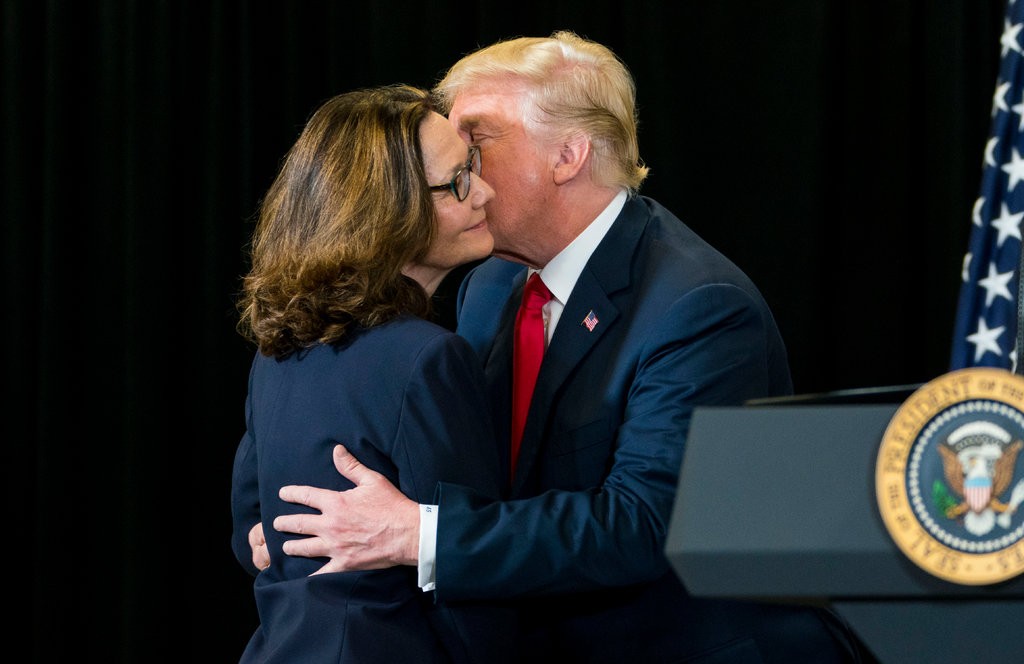

Gina Haspel Relies on Spy Skills to Connect With Trump. He Doesn’t Always Listen.

The C.I.A. director, Gina Haspel, appears to have struck a balance between sticking to her principles while also keeping the C.I.A. mostly free from President Trump’s ire.

Sarah Silbiger/The New York Times

By Julian E. Barnes and Adam Goldman

WASHINGTON — Gina Haspel was trying to brief President Trump early in her tenure as the C.I.A. director, but he appeared distracted. Houseflies buzzing around the Oval Office were drawing his attention, and ire.

On returning to her office, Ms. Haspel found a solution, according to two officials familiar with the episode, and sent it to Mr. Trump: flypaper.

Ms. Haspel, who will give only her second public speech as director on Thursday, has taken the reins of the nation’s premier intelligence agency at a difficult moment in its 71-year history, under pressure from a president often publicly dismissive of its conclusions and a White House that views national security professionals with deep skepticism.

As she approaches her first full year on the job, Ms. Haspel has proved an adept tactician, charming the president with small gestures and talking to him with a blend of a hardheaded realism and appeals to emotion. A career case officer trained to handle informants, she has relied on the skills of a spy — good listening, empathy and an ability to connect — to make sure her voice is heard at the White House.

ADVERTISEMENT

But her voice is not always heeded. For all of Ms. Haspel’s ability to stay in Mr. Trump’s good graces, there is little evidence she has changed his mind on major issues, underscoring the limits of her approach. Mr. Trump’s word choices on a range of issues — Russian interference in elections, Iran’s nuclear program, North Korea’s leadership and, most important, the culpability and reliability of Saudi Arabia’s crown prince — remain at odds with the C.I.A.’s assessment of the facts.

Unusually for a president, Mr. Trump has publicly rejected not only intelligence agencies’ analysis, but also the facts they have gathered. And that has created a perilous situation for the C.I.A.

Current and former intelligence officers assert that it is not Ms. Haspel’s role, nor part of her C.I.A. experience, to push for policies. Intelligence leaders should instead focus on delivering facts and assessments about what those facts might mean to policymakers, they said.

Ms. Haspel has served as a bulwark against politicization at the C.I.A., counseling senior agency leaders to focus on their jobs and ignore presidential comments telling intelligence chiefs to “go back to school,” former intelligence officers said.

“The C.I.A. is going through tough times because we have a president who says inaccurate things about the intelligence community and his understanding of the facts is questionable,” said Nicholas Dujmovic, the director of the intelligence studies program at the Catholic University of America, who served as a C.I.A. officer for 26 years. “The message to the intelligence community is to hunker down. This will pass.”

The first woman to run the C.I.A., Ms. Haspel has focused instead on shoring up the basics, like rebuilding morale, pushing more officers into overseas positions and emphasizing core spy skills like language expertise. All that has made her popular with the rank and file.

Ms. Haspel declined to be interviewed for this article, which was based on interviews with more than a dozen current and former intelligence officials who have briefed or worked alongside her.

Ms. Haspel remains in good standing with the president in part because she has directed the agency to focus on Mr. Trump’s priorities — like tracking and aiding American hostages held overseas — in addition to its regular work, former officials said.

“Haspel is a case officer, and case officers have extraordinary people skills,” said Fred Fleitz, a former C.I.A. officer who served on the National Security Council staff in the Trump administration. “They are remarkably good with senior officials. They know how to connect.”

The keys to talking to Trump? Realism and emotion

Soon after the president tapped her to run the C.I.A., Ms. Haspel solidified her reputation as one of the most skilled briefers of Mr. Trump, according to people familiar with her presentations.

Last March, top national security officials gathered inside the White House to discuss with Mr. Trump how to respond to the nerve agent attack in Britain on Sergei V. Skripal, the former Russian intelligence agent.

London was pushing for the White House to expel dozens of suspected Russian operatives, but Mr. Trump was skeptical. He had initially written off the poisoning as part of legitimate spy games, distasteful but within the bounds of espionage. Some officials said they thought that Mr. Trump, who has frequently criticized “rats” and other turncoats, had some sympathy for the Russian government’s going after someone viewed as a traitor.

During the discussion, Ms. Haspel, then deputy C.I.A. director, turned toward Mr. Trump. She outlined possible responses in a quiet but firm voice, then leaned forward and told the president that the “strong option” was to expel 60 diplomats.

To persuade Mr. Trump, according to people briefed on the conversation, officials including Ms. Haspel also tried to show him that Mr. Skripal and his daughter were not the only victims of Russia’s attack.

Ms. Haspel showed pictures the British government had supplied her of young children hospitalized after being sickened by the Novichok nerve agent that poisoned the Skripals. She then showed a photograph of ducks that British officials said were inadvertently killed by the sloppy work of the Russian operatives.

Ms. Haspel was not the first to use emotional images to appeal to the president, but pairing it with her hard-nosed realism proved effective: Mr. Trump fixated on the pictures of the sickened children and the dead ducks. At the end of the briefing, he embraced the strong option.

The outcome was an example, officials said, of how Ms. Haspel is one of the few people who can get Mr. Trump to shift position based on new information.

“Her style and the way she projects herself in these kind of senior situations is disarming, without showing weakness,” said Doug Wise, a former C.I.A. officer who has worked with Ms. Haspel.

Big losses and small wins

Co-workers and friends of Ms. Haspel push back on any notion that she is manipulating the president. She is instead trying to get him to listen and to protect the agency, according to former intelligence officials who know her.

C.I.A. officers are warned not to use their recruiting abilities on colleagues or other United States officials. But those skills come naturally and are hard to turn off, former agency operatives said. One unstated practice among C.I.A. station chiefs has long been to recruit the American ambassador, the person in the best position to help them succeed.

And there is little danger of Mr. Trump thinking the intelligence community is bending to his worldview, other officials said. Indeed, probably no example shows the limits of Ms. Haspel’s influence better than the administration’s reaction to the killing of the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

The C.I.A. assessed that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, whom the White House has courted, was culpable in the strangling and dismemberment of Mr. Khashoggi.

Many on Capitol Hill found Ms. Haspel and the C.I.A. persuasive. Mr. Trump did not, releasing a long statement about why he was not going to alter American policy on Saudi Arabia or end support for Prince Mohammed.

On other issues, Ms. Haspel has won Mr. Trump’s trust by seizing on his interests that intersect with the intelligence community’s agenda. Early in her tenure, Mr. Trump asked for updates on hostages held in North Korea, Iran, Yemen and elsewhere. Ms. Haspel told her C.I.A. deputies to prioritize hostage cases, to make sure the latest developments were available in presidential intelligence briefings.

Ms. Haspel, who has extensive field experience with hostage cases, got personally involved in the case of Robert A. Levinson, the former F.B.I. agent and onetime C.I.A. analyst who disappeared in Iran in 2007. She met with Levinson family members in July, weeks after taking office, and has ramped up efforts inside the agency to figure out what happened to him.

Learning from experience

As Mr. Pompeo’s deputy, Ms. Haspel served as a buffer, they said, coaching bureaucrats on how to talk to him. She quickly became a trusted adviser, who had credibility from surviving a dark period: the C.I.A.’s interrogation and detention program that grew out of the frantic pursuit for Qaeda conspirators in the months after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Ms. Haspel was chief of base at one of the C.I.A.’s secret prisons in Thailand, where Qaeda terrorists were tortured, including under her watch. She also served as chief of staff to Jose A. Rodriguez Jr., the divisive C.I.A. officer who decided to destroy 92 tapes of agency interrogations, some of which showed torture of a Qaeda terrorist.

During her Senate confirmation hearing last year, senators questioned Ms. Haspel’s judgment over her role in the destruction of the tapes. Ms. Haspel defended it as a move to protect C.I.A. officers but said she would consult more widely if she were in a similar situation now. “Experience,” she said, “is a good teacher.”

Her experience has made her cautious and fiercely protective of the C.I.A., viewing it as in need of safeguarding in a turbulent political environment, lawmakers who have worked with Ms. Haspel said.

Ms. Haspel won the trust of Mr. Pompeo, however, and has stayed loyal to him. As a result, Mr. Trump sees Ms. Haspel as an extension of Mr. Pompeo, a view that has helped protect her, current and former intelligence officials said.

But former officials have wondered how long that will last. Other senior national security officials, bureaucratic veterans like Jim Mattis and H. R. McMaster, saw their influence decline as they pushed policies at odds with Mr. Trump.

Ms. Haspel’s relationship with Mr. Trump has kept the agency at the table in the White House, said Andrea Kendall-Taylor, a former C.I.A. analyst who is now a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security.

“But as she continues to present facts and analysis that differ from what the president wants to hear, especially on high-profile issues like Russia and North Korea,” Ms. Kendall-Taylor warned, “her influence will wane.”

An earlier version of this article misstated the C.I.A. tenure of Nicholas Dujmovic. He served as an intelligence officer for 26 years, not 23.

Eric Schmitt, Michael S. Schmidt and Matthew Rosenberg contributed reporting.

- Previous 11 dead in Syria clashes between Russia troops and pro-Iran militias

- Next ‘CHINA HAS NOT WASTED A SINGLE PENNY ON WAR’