Is China’s propaganda machine losing the public relations battle with the US?

- Beijing’s tight grip on all forms of communication linked to the trade war could be doing it more harm than good, analysts say

- The one exception is Huawei’s 74-year-old billionaire founder Ren Zhengfei

During a lecture at Renmin University in Beijing last week, prominent economist Yu Yongding had a question: why have none of the Chinese companies accused of intellectual property theft by the US spoken out to defend themselves and dispute the charges?

“China has failed very much in this propaganda war,” said Yu, a former adviser to the People’s Bank of China.

“This is something we need to fix. Otherwise, in the sphere of public opinion, even something we are justified in doing would become unjustifiable.”

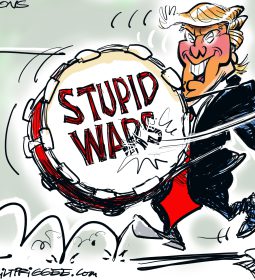

As Yu highlighted, while US President Donald Trump has tweeted about China more than 100 times since the start of the trade war last July, the Chinese government has been far quieter.

Analysts say this communication asymmetry has allowed the US to dominate the trade war narrative, as Beijing relies on its carefully managed state media coverage for its side of the story, which struggles to engage international audiences.

The hurdles for the bureaucratic Chinese propaganda machine centre on its lack of understanding of the Western public, restrictions for coverage to toe the official line, and existing preconceptions about China.

“The ineffectiveness of the [Communist Party’s] media strategy is evident in the trade war,” said Jonathan Hassid, an assistant political science professor who researches Chinese media at Iowa State University.

“Although few world leaders – or the populations they lead – have any sympathy or trust for Trump, no one trusts the [party] either. And so Trump has been able to effectively control the international press narrative even in the face of a relatively hostile media.”

While Xi was meeting Trump in Osaka, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei was at his company’s Shenzhen campus speaking to reporters about the future of 5G technology and how Canada could get out of its current tangle with Beijing over the arrests of two Canadians in China accused of stealing state secrets.

Since his daughter, Sabrina Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Vancouver in December – she is facing possible extradition to the US to face charges of bank and wire fraud – the 74-year-old billionaire, who had spent decades avoiding the limelight, has given several interviews to the Western media.

Jiang Min, associate professor of communication studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, said Ren’s media appearances allowed him to appear “authentic” in front of an international audience.

“It’s very unusual for him to come out and tell his side of the story to an international audience,” said Jiang, who previously worked for Chinese state broadcaster CCTV.

“He had a chance to present his side of the story and he did reasonably well. But at the same time, he is not a PR person … there are a lot of cultural differences still, and the American audience for the most part, they don’t understand China very well,” she said.

Without a public face, Beijing has stumbled in the public relations battle in the US-China trade war as all senior Chinese officials are inaccessible for public comment. It largely relies on its army of government spokesmen, who only toe the official line in presenting its positions.

Where there has been success for China is in its control over the domestic narrative and conversation on the trade war, Hassid said. State-controlled outlets have received directives to tone down trade coverage and avoid certain topics. Rampant censorship on the Chinese internet, meanwhile, saw “trade war” and “United States” among the most censored terms on social network WeChat last year, according to WeChatScope, a University of Hong Kong project that logs censored articles on the app.

“But I would suspect that if and when the economy slows further, the disconnect between the rosy pronouncements of official media and the actual facts on the ground will produce some cognitive disconnect,” Hassid said.

And while state media such as People’s Daily splash editorial after editorial on their front pages, the long essays have virtually no impact on international audiences.

Even China watchers in the West are left to read between the lines of Taoran Notes, the social media account affiliated with official newspaper Economic Daily, or follow the posts from Hu Xijin, editor of state-run tabloid Global Times, just to work out Beijing’s side of the story.

“China still has a lot of room for improvement in its messaging,” Wei Zongyou, an international relations professor at Fudan University in Shanghai, said.

“This includes communicating accurate information to the US side, the channels and methods of sending information, and sharing information domestically,” he said.

Meanwhile, there are also different pieces in Chinese media for different audiences: those in mainland China, overseas Chinese-speaking audiences, and overseas non-Chinese speaking audiences. Trade-related commentaries from Peop le’s Daily – which has separate domestic and overseas editions – differ sharply when read in Chinese or in English.

The Chinese-language version of one Peopl e’s Daily commentary about US accusations of China’s forced technology transfers said: “Some in the US turned a blind eye and a deaf ear, which is not a problem with their vision or hearing, but a problem with their minds and mentality. The result is what people of the world see as a moronic way of thinking, which they wallow in and cannot free themselves from!”

The English-language version was milder: “Some people in the US turn a deaf ear to the fact that China’s technological progress comes from the hard work, wisdom, and creativity of the Chinese people. Sticking to such a mindset, the US itself is becoming the laughing stock of the world.”

Zeng Yuan, a political communication expert at the University of Leeds, said the Chinese media had sought to maintain a “subtle balance” in conveying nationalism domestically without sounding too hawkish to foreign audiences, while the English versions used less aggressive language.

She described the Chinese propaganda campaign – a singular mode of information in China – as not being particularly effective against the diversity of voices in the US from Trump supporters and critics. Part of it was a lack of transparency on the Chinese side, resisting US claims without providing specifics, while the other was the inherent credibility problem of China’s state media, she said.

Beijing requires its media outlets to present only the official narrative, and party leaders have told them to promote “positive propaganda as a main theme” and “tell China stories well”.

“Before you even open your mouth, people already know you are party owned, you are state media, so whether it is true or not, there is already this prejudgement that you will be lying or just talking on all the official lines,” Zeng said, in reference to the appearance of Chinese news anchor Liu Xin on the Fox Business Network in the US in May.

“It starts from the very beginning in terms of credibility, which you have lost.”

Liu, who spoke about trade with Fox host Trish Regan, said she gained an unprecedented chance to “talk to everyday Americans in their living rooms” and show them that a Chinese state media person is “also a regular person”.

Jiang said audiences in China and the US had largely taken cues on the trade conflict from domestic commentators such as Hu from Global Times, who can be nationalistic in his writing.

There had been a fundamental “framework of miscommunication” between the two sides, with the Chinese media clearly more constricted in its messaging, she said.

“The situation is a really, really difficult one because China is now seen in the US as the next big challenge for the US. As much as you can negotiate and manoeuvre and sell your story, the broader strategic conflict between the two is sort of the trap for China, and it’s really hard to get out of.”

Additional reporting by Orange Wang

- Previous Beijing to prepare for decoupling from US

- Next Nepal denies Tibetans’ request to hold Dalai Lama birthday celebration