Kyrgyzstan Through First Sovereign Bond Wants to Decrease Dependence on China

Image: TCA, Aleksandr Potolitsyn

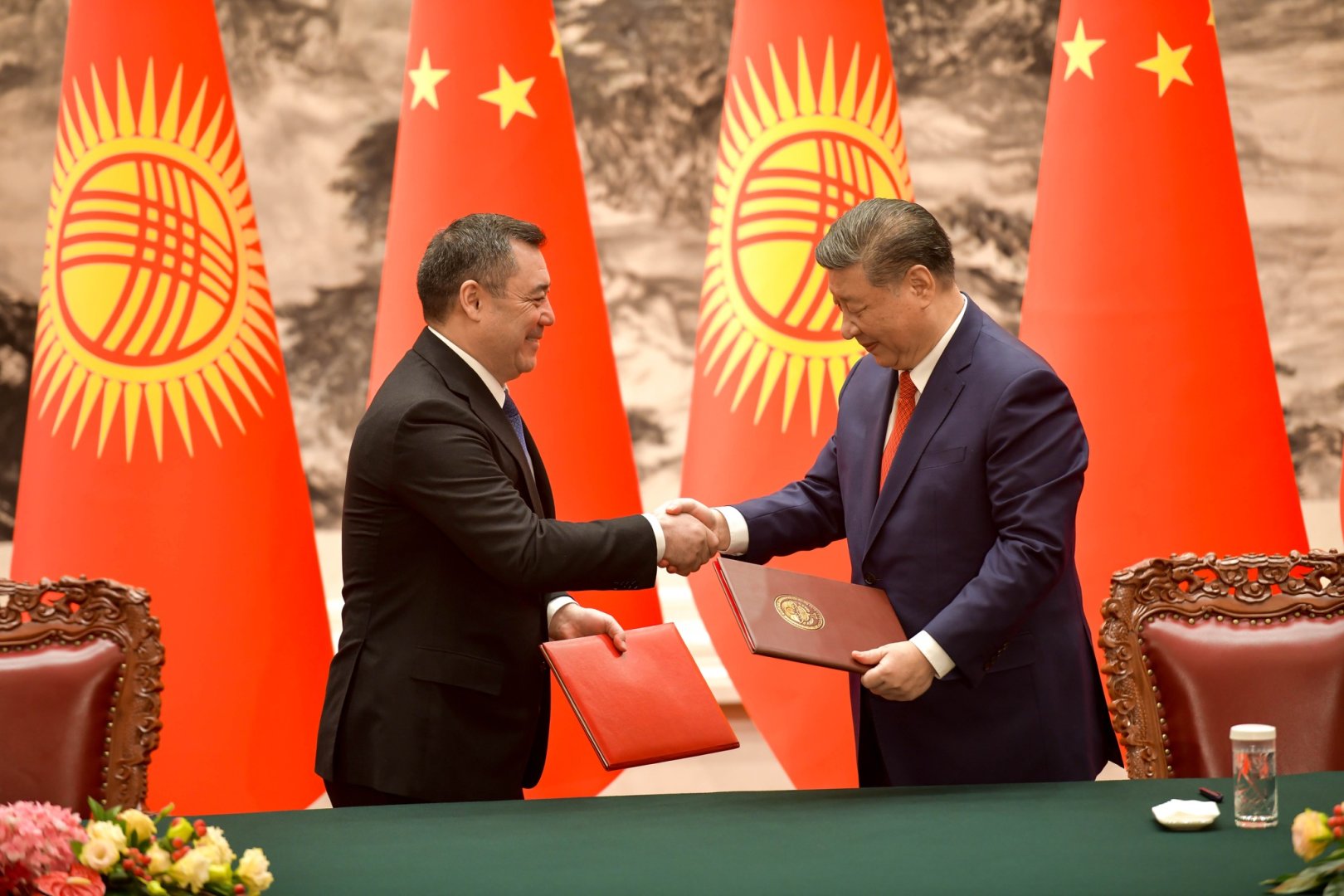

On February 4, Kyrgyz president Sadyr Japarov embarked on a four-day state visit to China, visiting Beijing and the northern city of Harbin for the opening ceremony of the 2025 Asian Winter Games.

The visit comes against a backdrop of increasing engagement between Bishkek and Beijing. Temur Umarov, a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, says that certain groups within the government are worried about an overreliance on China. “This is the problem of the current political leadership,” Umarov says. “They want to do more with China … they want to have more investment from China, but they have this debt that they inherited from the previous administrations.”

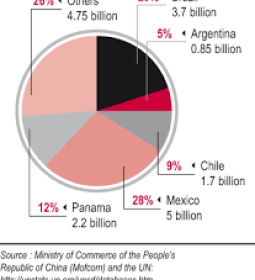

Indeed, 36.7% of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign debt is now owed to the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), Beijing’s state-run lender which traditionally deals with foreign investments. China is also responsible for 46% of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign trade. With Russia hemorrhaging influence in the region amid its ongoing war in Ukraine, accessing new sources of investment has risen up the agenda in Bishkek.

The Name’s Bond

A key plank of these diversification attempts was put forward on January 13, when the Minister of Economy and Commerce, Bakyt Sydykov, announced plans to raise $1.7 billion through the sale of ten-year sovereign bonds in Hong Kong.

“The country intends to tap into the international market for the first time,” Sydykov said. “We want to use Hong Kong’s role as a financial center to attract more potential investors, probably more diversified investors.”

For Iskender Sharsheyev, an economist, this turn to the global markets cannot come soon enough. “This should have happened thirty years ago,” he says. Sharsheyev notes that the groundwork has been laid over the last few years, with ratings agency Moody’s reaffirming its B3 credit rating last year and projecting a “stable” outlook for the country.

The yield of these bonds has yet to be announced, although Sharsheyev expects it to be reasonably high. “We expect that [the yield] will be worse for our country than for other countries, because, firstly, we are just entering. Secondly, the new flow of cash into the country could create risks; it can also spur inflation.”

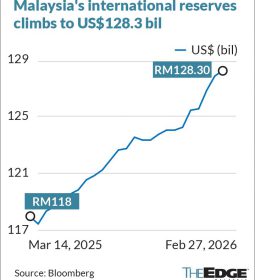

However, the high yield and the risk is seen as worth the cost. “The bond offering is an example of how Kyrgyzstan is trying to balance out its debt portfolio and have diversified ties with different creditors,” says Umarov. He notes that this mirrors a trend seen across Central Asia, where bonds have not traditionally been used as a means of fundraising but have become increasingly popular over recent years. In October 2024, Kazakhstan issued its first dollar-denominated Eurobond since 2015, the 10-year bond raising $1.5 billion with a yield of 4.714%.

Sharsheyev believes that some of the proceeds of the bond sale will be used specifically to head off debts to Beijing. “China is the main [source of] pressure. To maintain sovereignty, we have begun to service the external debt. Our country has spent an average of $400-500 million on paying off its foreign debt annually for the last three years,” he says.

Beijing’s Growing Influence

However, in a sign that Kyrgyzstan will not easily escape Beijing’s orbit, in the same week as it announced the bond issuance, the Mayor of Bishkek, Aibek Zhunushaliev, also confirmed the involvement of the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) in a large scale plan to reconstruct much of the center of Bishkek, including relocating the city center railway line, the reconstruction of the northern bypass road, as well as building a series of intersections.

The current railway line which dissects the city of Bishkek; image: Joe Luc Barnes

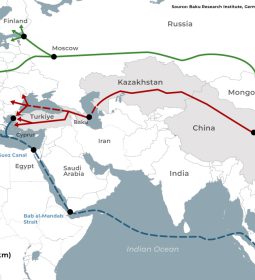

This is in addition to recent Chinese investment projects including the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, officially launched in December 2024; and a new electric vehicle factory built by China Hubei Zhuoyue Group, set to open later this year.

Felix Chang, a Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, believes Beijing is taking advantage of Russia’s distractedness to strengthen its position in Central Asia.

“China has been offering loans, building infrastructure, and increasing trade with Central Asian countries, surpassing Russia in several categories. All this gives China greater influence over the commercial activities of the region and reduces Central Asia’s traditional reliance on Russia,” Chang says.

This has caused disquiet in some quarters, particularly the suggestion by Mayor Zhunushaliev that, in lieu of paying CRBC for Bishkek’s railroad relocation project, the company would simply be given the land occupied by the current railroad.

However, most are optimistic about China’s increased investment. Sharsheyev is delighted at the prospect of relocating Bishkek’s railway, which he believes will help to significantly reduce traffic in the city center. As for the land being given to China Road and Bridge Corporation, “they will probably just build houses on it and sell them,” he says dismissively.

Umarov is similarly untroubled by China’s involvement in rail infrastructure. “I would have been much more concerned if it was something connected to exclusive rights on mining of gold or something like that. But the railways, I think this is a far less sensitive area – a lot of countries involve foreign companies in this regard.”

Diversification

Besides, Kyrgyzstan has other neighbors which it deems to have excessive influence. Indeed, one reason for Kyrgyzstan’s enthusiasm for the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway, which will see Kyrgyzstan receive goods directly from China by rail for the first time, is that it will reduce its reliance on transit routes through Kazakhstan.

Sharsheyev accuses Russia and Kazakhstan of deliberately seeking to hold back the Kyrgyz economy to create dependence. “You can measure the benefits of the railway simply by looking at the costs of Kazakhstan closing the border,” he says, going on to cite occasions in 2005, 2010, 2017, 2019 and 2020 when Kazakhstan unilaterally closed the frontier with its Southern neighbor. Moreover, Kyrgyzstan has repeatedly blamed Kazakhstan for causing delays at the border which are disastrous for the exporters of perishable goods.

The disproportionate influence that Kazakhstan can exert through these border closures has convinced many in Bishkek that the new China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan rail link, even if taken on with costly debts, presents not so much a threat, but necessary diversification. That is in addition to the transit payments that Kyrgyzstan will be able to garner for goods passing onward through to Uzbekistan and potentially the Middle East.

“We have an idea that the purely economic value of this 200-kilometer branch of railway is worth about $2 billion to the national economy,” says Sharsheyev.

What China Wants

Regular visits from the heads of state such as Japarov also allow Beijing to present a powerful image to the world.

“Xi Jinping generally prefers foreign leaders to visit China, as it allows him to project China’s strength, maintain control over the narrative, and reinforce the perception of Chinese leadership,” says Chang. “All of which, together, enables Xi to enhance his image both at home and abroad.”

But aside from the political imagery, Kyrgyzstan offers opportunities for Chinese companies as the domestic economy sputters. Beyond that, a growing and prosperous neighbor is also in China’s interests.

“What China really wants is to see the Kyrgyz economy be stable, predictable,” says Umarov.

- Previous USAID allocated $15.2 million to Kazakhstan in 2024: Now its is gone – crying Kazakh “progressive DIE activists

- Next Marshal Sisi in desperate look how to respond to Trump’s Gaza seizure plan