My way or the Huawei: how US ultimatum over China’s 5G giant fell flat in Southeast Asia

My way or the Huawei: how US ultimatum over China’s 5G giant fell flat in Southeast Asia

- 5G technology is coming to Southeast Asia, and the odds are Huawei’s technology will be driving it.

- That’s a slap in the face to a US that has been trying to poison the well against its Chinese competitor. So why is no-one listening to Uncle Sam?

When Malaysia’s deputy minister for international trade and industry, Ong Kian Ming, toured a Huawei training centre in Cyberjaya this week, the vibe was more “humdrum public relations opportunity” than it was “visit of epochal significance in a battle of East and West”.

Followed around by an entourage of interns, the minister gamely engaged in all the classic press conference moves: making small talk with trainees, commending the Chinese company for investing in his country and waxing lyrical about the coming 5G internet revolution.

There was ample time for snacks, a chat with Huawei Malaysia CEO Michael Yuan – in Mandarin, naturally – and, of course, the obligatory photo opp full of smiling faces and raised thumbs.

Yet half the world away in Washington’s corridors of power, it’s hard to imagine there were anything but grimaces.

Malaysia is just the latest in a string of Southeast Asian nations to have welcomed the world’s largest telecommunications company with open arms, flying in the face of warnings from the United States that doing so will leave their most highly classified secrets vulnerable to Chinese spies.

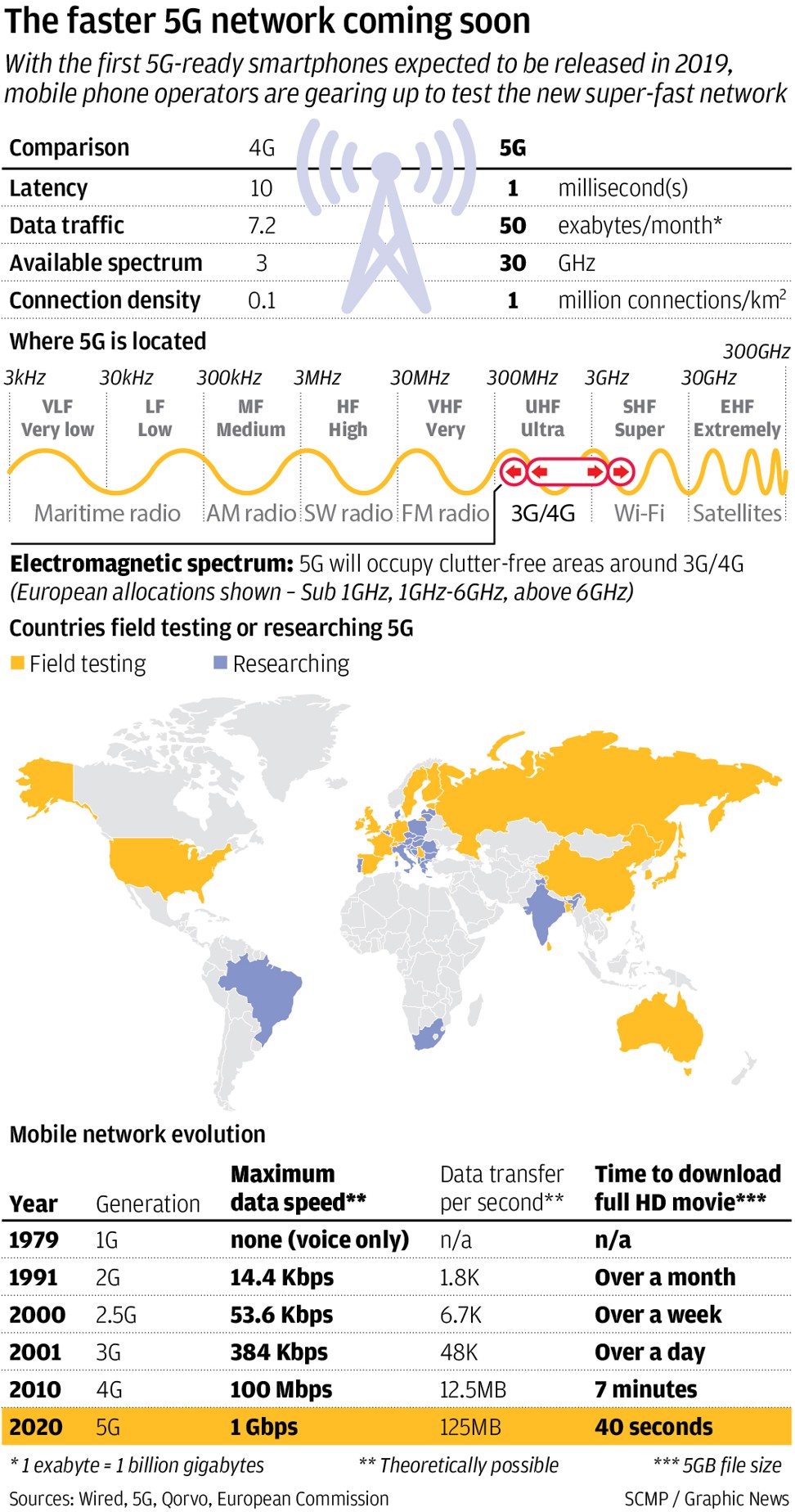

The region is shaping up as a key battleground in a war between the US and China to influence the rollout of superfast 5G internet services, billed by experts as an era-defining technological shift that could pave the way to breakthroughs in everything from artificial intelligence to the creation of smart cities.

In the West, the battles are going Washington’s way. Its claims that Huawei is a front for Chinese espionage have prompted every single one of its fellow members in the Five Eyes intelligence sharing community – Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand – to question the wisdom of dealing with the company.

But in Southeast Asia, where Huawei estimates there will be 80 million customers within the next year and US$1.2 trillion of business opportunities over the next five years, Washington’s fearmongering has had little impact.

Thailand hopes to roll out a Huawei-led 5G service by 2020 and is already carrying out joint research with the firm in its hi-tech Sriracha district; Singapore’s M1 service, Malaysia’s Maxis and Indonesia’s Telkomsel have all signed up to trial services with the company; and in the Philippines, a Huawei-backed service is to be introduced by the leading wireless provider Globe Telecom as soon as the second quarter of this year.

UNIMPRESSED

At the heart of Washington’s narrative is that Huawei could be compelled by Beijing to build in back doors, or hidden methods of accessing data, into its products that would enable it to spy on foreign competitors, steal intellectual property or even to shut down foreign infrastructure remotely.

The claims are, by their nature, almost impossible to prove but Washington has made much political mileage out of the fact its founder Ren Zhengfei was in the engineering corps of the People’s Liberation Army during the Cultural Revolution and has been a member of the Chinese Communist Party since 1978.

The US has pointed to the arrests of Huawei staff to underline its suspicions. In January, Poland arrested a Huawei executive on suspicion of spying for China – just one month after Ren’s daughter Meng Wanzhou, the firm’s chief financial operator, was arrested in Canada on allegations of selling US-made equipment to Iran.

But Koh Chee Koon, an ex-consultant for Huawei, said carriers in Southeast Asia were far less likely than their counterparts in the West to take notice of the US scare stories.

He noted that even the US’ treaty partners the Philippines and Thailand were going ahead with partnerships with the Chinese giant – despite suggestions that doing so would put at risk their military cooperation with the US.

“The narrative has been different in Southeast Asia because the threat perception is different in the region,” said Michael Raska, coordinator of the Military Transformations Programme at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

Or, as Huawei’s president of Southeast Asia James Wu put it in February: “We’ve already proven ourselves with a twenty-year cybersecurity record in Southeast Asia that Huawei can be trusted.”

Whether countries are right to trust Huawei or not, the evidence suggests they do: last year the company’s consumer business in the region grew nearly 50 per cent.

It’s not just that countries in Southeast Asia are less suspicious of China’s motives. Many have been seduced by its technological prowess. Huawei claims a 12 to 18 month advantage over its competitors, promising those who sign up to its technology the fastest and most advanced 5G networks in the world.

And not only is its technology more advanced that its Western competitors, it comes at a fraction of the cost – especially for those nations already using Huawei technology in their existing communications infrastructure.

“Huawei equipment not only has excellent performance, but also has the advantage of price. It is inevitable that more and more countries will choose cooperation with Huawei,” said Nie Wenjuan, assistant professor of international relations at China Foreign Affairs University.

For many, the choice between Chinese or Western technology is a matter of economics, not geopolitics.

ARE FEARS OVERSTATED?

Still, the US warns there are costs to doing business with Huawei. It says doing so is to court risks on various fronts – in everything from compromising the personal data of online video game players to jeopardising continuing military cooperation.

Some experts have even claimed nations that jump in bed with Huawei could at some point come under pressure to play by China’s rules on internet controls. As Raska at RSIS put it: “With building the infrastructure comes the advantage of the set of ideas of how to use it. The danger is that the Chinese vision of the future of the internet will be exported to other regions.”

But America’s undoubted ace card is its ability to threaten to withdraw intelligence or military cooperation.

This month, six former US military leaders issued a statement voicing concerns that, “Chinese-designed 5G networks will provide near-persistent data transfer back to China that the Chinese government could capture at will.”

“There is reason for concern that in the future the US will not be able to use networks that rely on Chinese technology for military operations in the territories of traditional US allies or emerging partners in Europe, Asia, and beyond,” said the statement, whose authors included two former commanders of the US Pacific Command.

GAME OVER ALREADY?

The problem for the US is that, in threatening to withdraw military cooperation or intelligence sharing, it is forcing Southeast Asian nations to make an impossible choice between two economic superpowers.

If it follows through on the threats, it could find it is pushing even former allies into China’s embrace.

“5G networks could dramatically change how militaries operate in the future. Southeast Asian nations may find they are no longer able to integrate US made weapons systems and platforms, which could further deepen dependence on China, making it harder to carry out joint training and security cooperation with the US,” said Timothy Heath, an analyst at Rand Corporation.

At the heart of the issue is which end of the 5G spectrum will be made available for commercial use.

The US government has encouraged tech companies to use the higher frequencies for commercial use – keeping the lower frequencies for its own secure communications. However, China has spent the past 10 years investing in commercialising the lower end, leaving US secure communications vulnerable.

As more countries like Malaysia show signs of calling America’s bluff, some warn Washington may have to come to terms with a future in which it is not the only superpower in the region – or face losing even more influence.

Vorasak Mahatthanobol, acting head of the Chinese Studies Centre at Chulalongkorn University, said that the US’ importance as a partner for Asean had decreased in recent decades as the bloc had become more dependent on China economically.

“Asean will not be affected,” said Vorasak. “I don’t think the US will [succeed in] pressuring the bloc to have conflict with China because of Huawei.

HEDGING BETS

Ultimately, Southeast Asian countries may be calculating that they face a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea. As 5G equipment must be imported from somewhere, it’s just a choice of who they’d rather have spying on them.

From there, it’s tempting to pick the cheapest option, especially when the deal is sweetened by the promise of local employment opportunities – in Malaysia, for example, Huawei has already created more than 2,500 jobs.

As Timothy Heath, a former analyst at US Pacific Command, puts it: “The omnipresence of new technologies will open new possibilities for services and convenience, but also for security vulnerabilities. This is true regardless of where a country adopts 5G tech from.”

There is also the lingering suspicion that America may back down on its threats if enough nations call its bluff, especially in the face of what are seen by many as unreasonable demands.

“It is unrealistic for Southeast Asia to preclude China as an economic partner,” said Muhammad Faizal at the Centre of Excellence for National Security at RSIS.

He suggested countries could hedge their bets when it came to balancing their own national interests while accommodating the big powers of the region. They could also be more proactive in taking technical measures to keep their cyber operations secure.

“If countries buy Huawei, it increases the technological challenge and the cost of sharing intelligence securely,” said James Andrew Lewis, director of the technology policy programme at the Washington think tank the Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

“But these are not insurmountable challenges as long as the countries don’t sit passively and are willing to spend on secure communications.”

Nie Wenjuan, at China Foreign Affairs University in Beijing, said framing the debate as a choice between one side or the other was itself an illusion.

“This is first and foremost a choice made by individual nations based on their own economic development, and we do not rule out that in the choice of the ultimate technology partner there may be cooperation with multiple actors,” she said.

While Raska at RSIS believes the US “hasn’t missed the boat yet”, with less than a year to go before a host of countries across the region plan to have Huawei-led 5G networks up and running, it won’t be long before this ship has sailed. ■

Additional reporting by Jitsiree Thongnoi, Tashny Sukumaran, and Zen Soo

- Previous PM Mahathir Mohamad to meet China’s Xi Jinping at sidelines of belt and road summit, as ties recover over ECRL project

- Next U.N. envoy sees troop withdrawal in Yemen’s Hodeidah within weeks