New Geopolitical Host Spot in East Timor. It wants to tap oil and gas near Australia, so why is it courting China?

- The young Southeast Asian nation is almost entirely dependent on oil and gas revenue as well as aid from richer neighbours

- But international energy firms have left the country in the lurch by pulling out of a critical offshore project near Darwin, leaving Dili with only one place to turn

to develop an offshore oil and gas field.

But despite the denial, experts say the country has few options other than to turn to China for a project which is vital to its struggling economy.

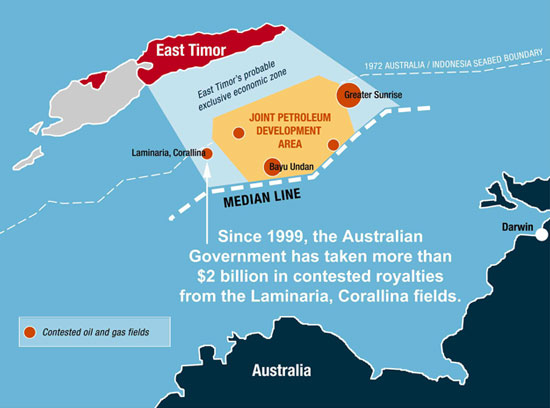

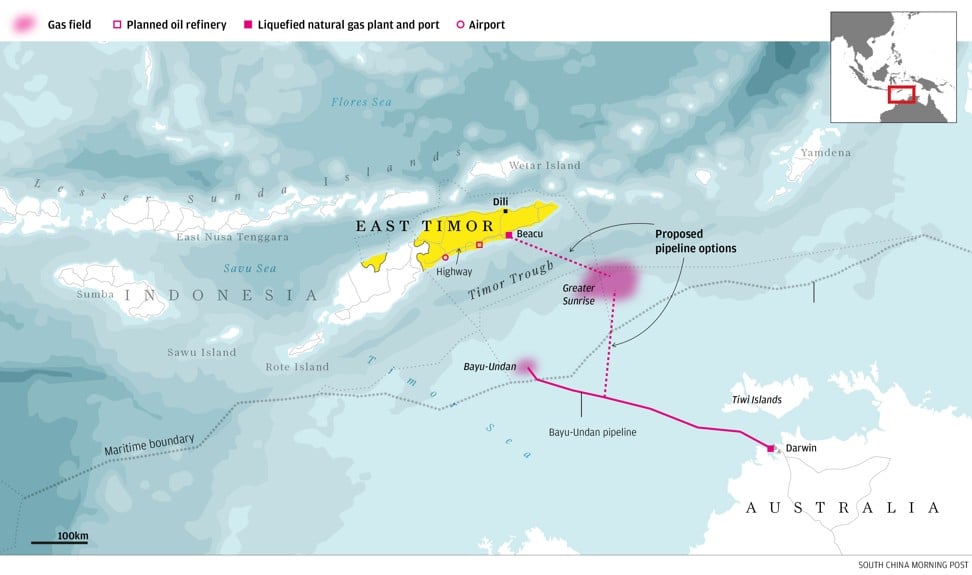

The oil and gas field is worth an estimated US$50 billion – more than twice the US$22 billion East Timor says it has generated since 2005 from its Bayu-Undan and Kitan fields. The Greater Sunrise site, located about 150km southeast of Beaço in East Timor and 450km northwest of Darwin in northern Australia, holds estimated gas reserves of 5.1 trillion cubic feet and up to US$12 billion worth of oil.

ECONOMIC STRUGGLES

NGO La’o Hamutuk, which monitors East Timor’s economic development, says the nation’s sovereign wealth fund currently foots the bill for about 90 per cent of the state budget.

The fund has stagnated at US$16 billion for the past four years, and over the same period the country’s revenue from existing petroleum projects has tanked – from nearly US$4 billion in 2012 to less than half a billion in 2017.

Tapping Greater Sunrise could mean draining the entire remaining sovereign wealth fund, La’o Hamutuk estimates.

Shell and ConocoPhillips recently sold their stakes in Greater Sunrise back to Timor Gap – partly due to the state’s inability to compromise on the logistics involved in getting the project off the ground.

La’o Hamutuk says international financial institutions are reluctant to bankroll the work, which they see as risky and challenging.

WHO ELSE BUT CHINA?

Tao Duanfang, an analyst at the Centre for China and Globalisation in Beijing, agrees. “Who could fund this kind of project other than China?” he says.

Timor’s national development strategy is “highly compatible” with the Belt and Road Initiative, believes Xiao Jianguo, Beijing’s ambassador to East Timor. Xiao last month said the prospects for future economic cooperation were “expected to be great”.

.

Chinese firms have also helped build a high-voltage electricity grid, which is already operating. They have had a hand in constructing the nation’s presidential offices, army barracks, and buildings housing the ministries of defence and foreign affairs.

PETROLEUM HUB

Exploiting the Greater Sunrise site will require a host of accompanying infrastructure, and here Beijing has also played a part. The East Timor government’s infrastructure push centres on the Tasi Mane project, which is intended to transform the southern coast into a petroleum-processing hub, with liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities in Betano, as well as a supply base in Suai and a port in Beaço, with a highway linking the three.

An estimated US$250 million has already been spent on Tasi Mane, including on the road between Suai and Beaço – the location of a proposed port and entry point for the pipeline – and for a new airport in Suai. Both have been built by Chinese state-owned China Overseas Engineering Group.

But reports indicate the highway has been blocked by debris from a landslide since January, and the new airport receives just a few flights a week.

East Timor’s Audit Court reportedly rejected a US$50 million deal signed in 2016 with the Export-Import Bank of China to revamp the drainage system in the country’s capital, Dili. In the same year a Chinese naval task force undertook a five-day official visit to the city.

China’s approach to East Timor was described in a leaked 2008 US diplomatic cable as lacking support for good governance and “distributing goodies with few strings attached”. The strategy has been slowly drawing the country into Beijing’s orbit.

PROBLEMS WITH THE NEIGHBOUR

Australia’s Woodside Energy, which remains the operator of the project, would prefer sending it through a new 210km pipeline to another one already running from the Bayu-Undan field to the ConocoPhillips LNG plant in Darwin.

Under this arrangement, Timor would still keep 90 per cent of the profits, as it does with the Bayu-Undan project, without shouldering the huge cost of building the infrastructure.

Bringing the gas to Timor requires building a pipeline under the sea across the Timor Trough, which Woodside and former stakeholders Shell and ConocoPhillips view as unnecessarily expensive and logistically risky.

But despite these objections, Timor Gap in April signed a US$943 million contract with China Civil Engineering Construction, a unit of China Railway Construction, to build facilities to support an LNG plant at Beaço, according to Portuguese media.

Meanwhile, Canberra has been dragging its feet on ratifying a maritime boundary treaty with Dili.

Australia is East Timor’s biggest source of aid, having sent more than US$800 million between 2006 and 2014, but Tao at the Centre for China and Globalisation says the relationship remains one of dependency. Canberra has provided support but not enough to ensure its neighbours can stand on their own two feet.

This, he says, is a recipe for resentment. ■

- Previous Ethiopia’s 6000 MGW and 60 bn tons HPS: Water crisis in North Africa dampens future

- Next Inia isolates Kashmir by shutting down