Opinion: Trump’s recognition or not, Israelis aren’t moving to the Golan, But how about use of scarce water resources in MEast!?

By Noah Schpigel

Plans to develop the region have been promoted for decades, but proved fruitless, and it’s unclear that Trump’s move will do anything for residents

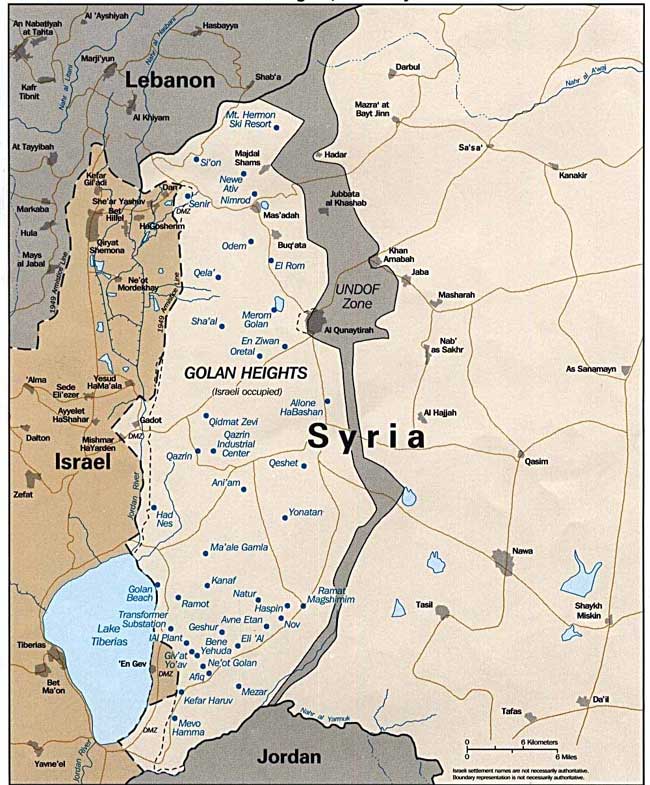

With his proclamation Monday recognizing Israeli sovereignty in the Golan Heights, U.S. President Donald Trump may have bolstered Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s election campaign, but it’s not clear he has helped anyone who lives in the region, whether Jews or Druze who’ve lived there since before Israel took over after the Six-Day War.

The peak of a grassroots campaign to ensure Israel retained the Golan came in the early 1990s, when for the first time the government made contacts with Syria about giving the region back. “The people are with the Golan” became a popular slogan and bumper sticker, but the area has never been the target of massive Jewish settlement like the West Bank.

Immediately after the war in June 1967, the government agreed that no Jewish settlements would be set up there, but by July 14 a group that would establish the first settlement, Kibbutz Merom Golan, went there with the support of some government officials and the army. By August, the government had approved farming in the region, but only 14 years later did the Knesset pass controversial legislation applying Israeli law to the Golan Heights, effectively annexing the area.

Trump’s proclamation may have added a layer of legitimacy, but neither that step nor the beautiful rustic landscapes nor the well-kept Jewish communities in the region have convinced many Israelis to move there. What has proliferated is the number of plans to increase the Golan’s population, and not much.

Fifty-two years after Israel captured the strategic plateau, there are, apart from four former Syrian villages, 32 Jewish communities dotting the area with a population of 17,600. Katzrin, which was established in 1977, may be the region’s urban center, but it’s no city. By the end of 2017 it had just over 7,000 residents.

“The person who more than anyone else pushed the government to settle the land was Levi Eshkol,” said Uri Heitner, a member of Kibbutz Ortal in the Golan, referring to Israel’s prime minister in 1967. “In the year and a half after the Six-Day War until his death, a third of the communities were established.”

Eshkol wanted to turn Quneitra, an abandoned Syrian city in the Golan that was returned to Syria in 1974, into the region’s urban center, but the Israeli army vetoed the idea, Heitner said. Heitner, the spokesman for the committee representing Golan communities during the grassroots campaign, is a researcher at the Shamir Research Institute in Katzrin on the history of settlement in the Golan.

As Heitner puts it, the three politicians who led the push to settle Jews in the area after the Six-Day War were Yigal Allon, who became deputy prime minister in 1968; Yisrael Galili, who replaced Allon as head of the ministerial committee on settling the land; and Haim Gvati, who was agriculture minister until 1974.

Heitner says the decision to establish Katzrin came immediately after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. “The center of the Golan had not been populated, and it was mostly there where the Syrians broke through,” he said, referring to the early stage of the war. Katzrin was established four years later, a decade after Kibbutz Merom Golan.

Another significant decision came in 1975 after the UN General Assembly passed a resolution declaring Zionism a form of racism. Then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin convened his cabinet, which decided that the right response was the establishment of three more Israeli communities in the Golan. That was followed in 1981 by the legislation extending Israeli law to the territory, effectively ending military rule there.

Druze majority

The following year, the Jewish Agency crafted a plan to get more Israelis moving to the region. The goal was to attract 20,000 new residents by 1987 and “develop industrial and tourist enterprises.”

Katzrin was at the center of the plans, but agricultural communities were also included, some existing ones to be expanded. Still, the Shamir Research Institute houses the documents of many failed plans for the area, most of them designed to increase the Golan’s population. In 1996, a plan aimed to increase the Golan’s Jewish population from 15,000 at the end of 1996 to 25,000 in 2000.

This foray failed, too; a September 1998 plan described the region’s population as “about 14,000 Jewish residents and about 15,000 Druze and Shi’ite residents.”

Those figures might also have been an exaggeration. “Over the years it was customary to add 20 percent to the number of people because they didn’t feel comfortable with the existing figures and the Druze majority,” said Yigal Kipnis of Ma’aleh Gamla in the Golan, a researcher of Israel’s diplomatic, geographic and settlement history.

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2017 there were about 25,600 Druze in the region.

A plan from January 1999 sought to attract 18,000 new Jewish residents. “The talk of doubling the number of residents is something that was repeated every time,” Kipnis said. “It was more of a public relations stunt. The plans to settle people were practical, but there was always a shortage of people to bring them to fruition.”

Kipnis says politicians like Benjamin Netanyahu “loved to love the Golan, but not so much to act on its behalf, because there aren’t a lot of votes there. This was very much the case with Netanyahu. On Election Day in 1996 he came to the Golan in a helicopter, swore allegiance to the Golan, and later conducted negotiations via Ron Lauder,” the American businessman who presented then-Syrian President Hafez Assad with a draft agreement for a full withdrawal.

This repeated in Netanyahu’s second term, Kipnis says. “He conducted negotiations for six months until the beginning of the Syrian Civil War. Now, too, the Golan is an election stunt.”

Israeli governments over the years haven’t invested in the Golan, certainly not like in the West Bank, Kipnis says. “You just have to look at the roads, though that’s not terrible. This has helped the residents live within their means and not milk the government on the ethical level.”

Lost decade

Eli Malka, who headed the Golan Regional Council from 2002 until late last year, says that from 1967 to 1980, lots of resources were invested in the Golan; that’s when the 32 communities were established.

“After that there was a period when they invested less in the Golan, and the years 1991 to 2001 were the Golan’s lost decade,” Malka said. “They negotiated with Syria from the Madrid Conference to the Geneva summit, and when they’re negotiating, people don’t come to live there.”

From 2003, things looked different, Malka says. “Significant government decisions were taken. A government plan for tourist and rural development was successfully carried out, as well as a special public transportation plan for the Golan. There was a project for investment in developing and populating 750 agricultural plots, and that’s coming to a successful conclusion.”

But Yehuda Wohlman, who headed the Golan Regional Council between 1987 and 2001, says the significant investment actually happened during the Rabin government from 1992 to 1995.

“It was the Labor Party that backed settling the land. It’s a shame that it lost its patriotic outlook. I’m not griping,” he said. “The Golan and the Galilee are both outlying areas, and there are things that can change the region regarding employment. A university in the Galilee would be dramatic for the Galilee and the Golan.”

Wohlman says the talk of doubling the population is repeated every election campaign, but since almost all Jewish communities in the region are agricultural or collective, there are limits to expansion.

“The Golan is still a limited area used for a variety of purposes,” he said. “The Israeli army trains there. There are pasture lands. There are areas with mine fields. It’s not as if it’s possible to settle on every mountain and under every bush.”

Shefi Mor, who has lived in Merom Golan since 1982, is more outspoken. “The state did it. The results are awful,” he said. “I don’t know how to measure millions of shekels, but the added value isn’t seen in the statistics for demographic growth.”

Even though in recent years, 1,000 to 1,500 families have come, basic services are lacking in the Golan and in the north in general – health, culture, transportation, jobs, he says.

“What employment is there in the Golan? Agriculture and tourism. There’s no industry here. Apparently the tax incentives aren’t enough and we can’t compete with Yoknea’m,” he said, referring to an area near Haifa with many high-tech firms.

Dimi Apartsev, Katzrin’s mayor since 2013, acknowledges the very gradual increase in the town’s population. “That’s not an achievement but I don’t belittle the effort that was put into it,” he said. In 2014, the government made significant decisions regarding the Golan, including for the Druze, he added.

“I can’t say that the government has forgotten us, but now there’s a possibility to develop it better,” he said. “It’s possible to bring the population up to 150,000 in a period of 10 to 20 years, depending on the extent to which it’s a priority. At the moment, Katzrin is on a growth plan for up to 22,000 people, but I also have plans to bring it up to 50,000.”

Lilach Ashtar, a strategic consultant from Nimrod in the northern Golan and a leader of the campaign in the ‘90s, notes the period between 1981, when the area was effectively annexed, and 1999, when legislation was passed making it more difficult to cede Israeli territory. She says that in that stretch the Golan Regional Council achieved equal status with its counterparts around the country.

“Israelis have understood that the Golan is an integral part of the country, so there’s no real pressure to settle it, either from the leaders or the people,” she said, noting that the West Bank, in contrast, has an Israeli military administration.

“They’ve been on the negotiating table for years, and the only way the leadership can win is demography. The Golan Heights doesn’t need that. We’re in the mainstream, so there’s a sense of calm and comfort, and the place attracts people of a high level, not necessarily for ideological reasons but more for the quality of life.”

- Previous China to be offered Russia’s ‘best warplane’ Su-57

- Next Uzbekistan suggests to host talks on Afghanistan