Pakistan is stuck in insecurity, rising threat from terrorism and conflict with Afghanistan

AFTER Zohran Mamdani’s victory as mayor of New York, academic Vali Nasr remarked on social media that the moment symbolised “the end of the era of the Global War on Terror”. Yet, for Pakistan, the supposed front-line state in that long global campaign, the war never truly ended but rather got worse. Ironically, nations once branded as epicentres of terrorism, Iraq, Syria, and even Afghanistan now appear relatively more stable. One must ask why Pakistan remains suspended in perpetual insecurity, despite once being the front-line state in the war against terrorism.

The state has found many excuses to explain terrorism within its borders, blaming Afghanistan, global jihadist networks, local militant groups and religious extremism. Yet it rarely reflects on the policies it crafted to remain relevant in the region’s strategic game. These policies were marred by miscalculations regarding the strengths and weaknesses of militant groups, and more critically, by persistent policy failures. Successive governments and security institutions have refused to admit these mistakes, hold anyone accountable, or meaningfully reform the frameworks that consistently failed to deliver.

The irony lies in the fact that Pakistan’s security apparatus continued to implement the very approaches that had proven ineffective. Instead of acknowledging their flaws, it became defensive and intolerant of criticism, silencing legitimate forums and institutions that could have questioned these policy failures and ensured even minimal transparency in decision-making.

Apparently, the state institutions have decided to address the problems of terrorism and extremism decisively. This renewed resolve is reflected both in Pakistan’s posture towards Afghanistan and in how the state has dealt with the extremist group TLP in Punjab. However, once again, these policies are being implemented with full impunity, and it remains unclear who’ll be held accountable if they fail to deliver the desired outcomes.

State institutions must not lose their composure in their display of muscle.

In recent times, civilian governments have borne the burden of the strategic blunders made by state institutions. But under the current hybrid system, there is little room left to shift the entire responsibility onto civilian shoulders. The civilian leadership today appears to be in complete synchronisation with the military establishment in its approach to security, the economy and politics.

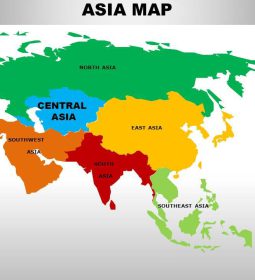

The synchronisation has created relative political stability in the country, but it is unable to address the security challenges that Pakistan is facing. What happened in Doha and Istanbul during the dialogue between Afghanistan and Pakistan showed that Pakistan, which had facilitated the Doha dialogue between the Taliban and the US, was now itself in talks, enabled by Turkiye and Qatar, with the Taliban regime. And in these talks, the bone of contention remained the terrorist groups TTP and the Ittihadul Mujahideen led by Gul Bahadur, and terrorist activities inside Pakistan.

Both these terrorist groups were close aides of the Taliban in their fight against Nato forces, and clearly, Gul Bahadur had been Pakistan’s proxy to support the Taliban insurgency. The TTP, which was equally lethal in Afghanistan and Pakistan, was tolerated for several years in North Waziristan until Operation Zarb-i-Azb was launched. Once again, the group was engaged in talks.

It was a deliberate policy to bring the Taliban into power in the hope that they would strengthen the state’s strategic interests on the western borders. The price was so high that it bled Pakistan and caused disharmony inside it. The approach to supporting the Taliban had only one objective — to bring them to power; the state institutions did not have any plans once they came to power.

The Haqqanis, considered close to the state, have turned against Pakistan — something that should have been a strategic shock, but was absorbed silently. Neither the state institutions nor the intelligentsia in Pakistan questioned why the Haqqanis wanted to reverse Fata’s status and convert the area once again into tribal territory, where they could operate freely, sustain their political economy, and continue spreading radicalism in Pakistan. The TTP and Gul Bahadur are merely the Haqqanis’ stooges in this plan.

The irony lies in Pakistani officials signalling the possibility of regime change in Afghanistan if the Taliban do not comply with their expectations, an approach that violates diplomatic norms. Yet analysts are raising a valid question: if the state were to attempt regime change in Afghanistan, who would be its closest ally? Who else, if not the Haqqanis?

This is not just a dichotomy in the state’s approach; it reflects a mindset rooted in the concept of a ‘hard state’, where the application of hard power often clouds the distinction between friends and foes. The state appears to be focused solely on achieving its set objectives, regardless of the long-term consequences.

One hopes that whatever policy the state has crafted to deal with terrorism and extremism, it will deliver tangible results and allow Pakistan to finally declare victory over this decades-old scourge. However, state institutions must not lose their composure in their display of muscle. A ‘hard state’ should not mean a loss of reason; it must evolve long-term policies to address its challenges.

Anatol Lieven’s central argument in Pakistan: A Hard Country is that Pakistan is not a ‘failed state’; rather it has a weak state apparatus that governs a socially resilient society. The idea derived from his analysis is that a muscular state could strengthen itself through firmness and control. However, as seasoned former diplomat Ashraf Jehangir Qazi recently reminded us, quoting Swedish economist and sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, Pakistan today is “characterised by weak governance, a lack of effective law enforcement, and a general societal and political indiscipline” — a reflection of Pakistan’s current political condition. As he wrote in these pages: “Reliance on the use of force to resolve complex political challenges is not an indication of a strong or hard state.”

The writer is a security analyst.

- Previous China’s DeepSeek – AI ‘whistle-blower’ on job losses

- Next Mamdani’s New York victory exposes fault lines in Jewish Democratic politics