Pakistan must talk frankly about its Afghan worries.

PAKISTANI officials will tell you that they see the Donald Trump presidency as an opportunity for Pakistan-US relations. The relationship had frayed in the last 18 months of the Obama administration. They wish to reset the tone.

To do so, they must engage. The ongoing Afghanistan policy review in the US offers the obvious opportunity. So far, I haven’t seen any serious effort to reach out. US National Security Adviser Gen McMaster visited Pakistan last month but this only allowed brief meetings with the prime minister and army chief.

I sense a bit of nervousness to engage. They lack personal rapport and connections with the Trump administration and don’t have the best feel on who to tap. But I think the real hesitance comes from not knowing how to reshape the conversation.

This is a valid concern. For, if all one is going to do is rehearse set talking points, it risks leaving both sides further convinced of the futility of engagement.

Pakistan must talk frankly about its Afghan worries.

Pakistan could, however, change this by being totally honest about its concerns in Afghanistan. Doing so offers the best hope to identify a realistic way forward in the Pak-US relationship.

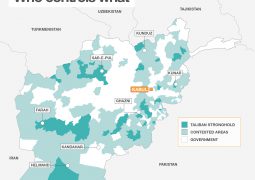

First, Pakistan needs to move away from its denial of the Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network still, allegedly, operating from its soil. US intelligence sources say they are convinced, not only of the presence of these outfits in Pakistan but of material support to them by the establishment.

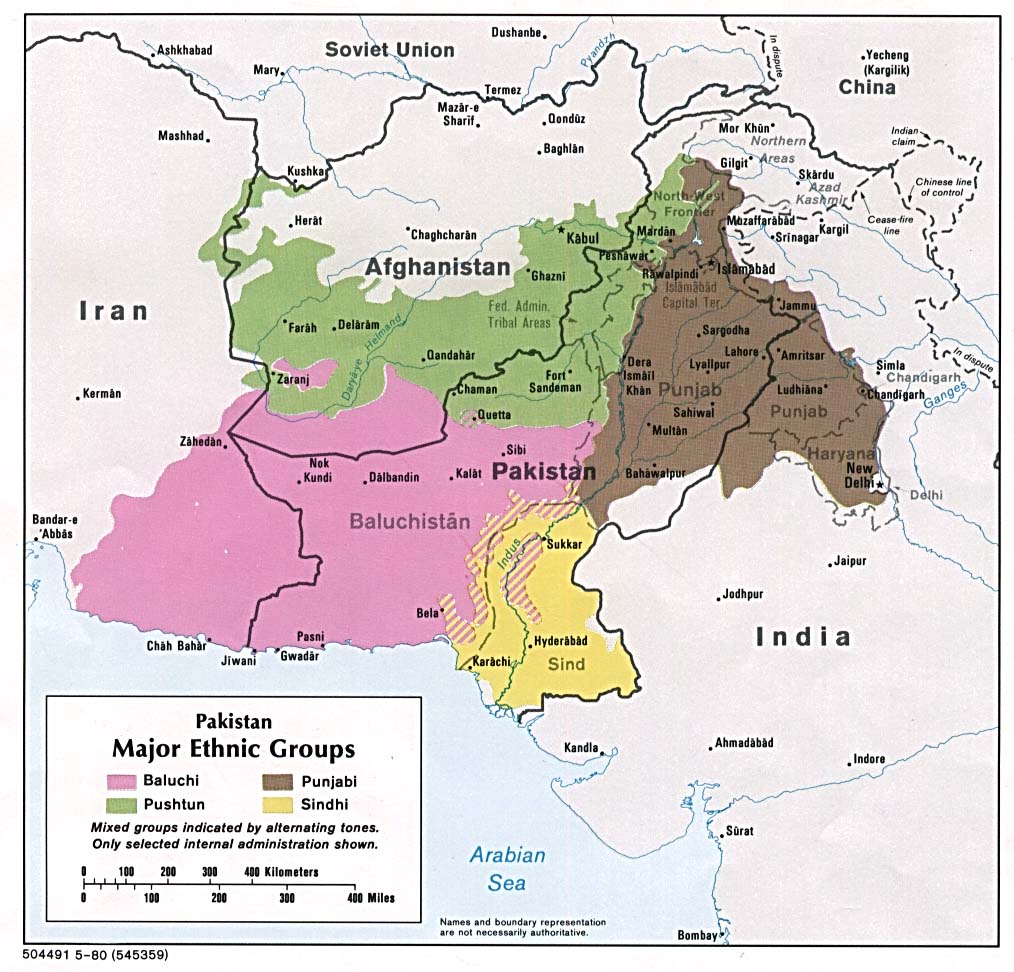

As far as I can tell, the state believes that the US is not sincere about engaging the Afghan Taliban in a peace process and still wants to defeat them militarily. It is worried that this would leave behind an Afghanistan friendly to India and hostile towards Pakistan.

There is also the concern that military action against them on Pakistani soil will drive them closer to Pakistani militants and destabilise Pakistan further. This isn’t a difficult one to explain to the US but it should be done judiciously rather than presenting an apocalyptic scenario — especially now that the state has a better handle on internal threats from the Pakistani Taliban and their affiliates.

Third, Pakistan should stop saying that it has lost leverage over the Afghan Taliban. If Pakistan pledges inability to deliver authoritative leaders of the insurgency to the negotiating table, how does it consider itself worthy of a seat at this table? Instead, Pakistan should acknowledge its links, complicated as they are, and promise to do whatever it can to pressure the Afghan Taliban to negotiate seriously.

Fourth, Pakistan should accept that its Afghanistan policy continues to be driven by its anxieties about Indian presence in Afghanistan. It needs to be specific about what bothers it, and why. The state has done itself no favours by continuing to raise this concern without providing evidence to convince sceptics. This must change.

For starters, such a conversation will signal a change in Pakistan’s approach. This is important because the US side feels jaded by the set discourse that they say has amounted to little more than hollow promises of cooperation from Pakistan in the past.

More importantly, this approach will create a space for a new, more practical and honest conversation about the way forward.

This would entail a US effort to offer ways that would ascertain its seriousness about a peace process that seeks to fold the Afghan Taliban into the political mainstream in Afghanistan. Pakistan would have to suggest how it will prove its support to convince the Taliban to negotiate an end state within the confines of the Afghan constitutional framework.

Discussion about Taliban sanctuaries would focus on steps Pakistan could take short of a blanket military operation against them. These would amount to serious efforts to curtail their ability to perpetrate violence across the border, which remains a prerequisite for the Afghan government to be able to initiate a peace process with the Afghan Taliban. Both sides would need to agree to verification mechanisms that confirm Pakistani actions in pursuit of this agenda. In return, the US could push the Afghan government harder to act against the TTP presence in Afghanistan.

On Indian presence, the two sides could identify any Pakistani concerns that need immediate attention. Meanwhile, the US could encourage India and Pakistan to initiate a discreet dialogue on Afghanistan with an eye on finding a workable formula for peaceful coexistence.

The US and Pakistan have more to lose by disengaging on Afghanistan than by continuing to strive to find common ground — however imperfect the overlap in their positions may be. But this won’t happen without proactive efforts to engage by both sides, and without changing the tenor of their policy discussions. More importantly, even engagement will come to naught unless there is genuine commitment to act on the agreements they reach. Pakistan has an opportunity to make this work with the Trump administration.

The writer is a foreign policy expert based in Washington, D.C.

Published in Dawn, May 23rd, 2017

- Previous President Donald Trump’s Visit to Western Wall Highlights Differences With Israel

- Next Triple talaq undesirable, practitioners to face boycott: Muslim board to SC The affidavit, filed by AIMPLB in the SC, also speaks of excluding the provision of triple talaq from the nikahnamas (marriage contracts).