Portugal: a new home for those who fear Hong Kong’s fate?

- Growing frustration over extradition bill and worries over erosion of city’s freedoms have seen a surge in number of Hongkongers considering migration

- For those who want access to Europe, Portugal is increasingly seen as a gateway – either through family ties in Macau or investment

Lam, a data expert working for a top Hong Kong-based company, was born and bred in Kowloon Bay. But the city she once knew has vanished among mainland Chinese tourists’ shopping bags, crowded pavements and – most worryingly, she says – diminishing freedoms.

“It made me revisit this idea. I don’t think I want to raise my [future] kids here,” says Lam, who asked to be addressed only by her surname. “The No 1 reason is the government and the tightening grip of Beijing over Hong Kong, regardless of how society here feels.”

As protests continue to unfold in several districts, frustrations and anxiety over the city’s fate have led to an increase in number of residents seeking options for a life elsewhere.

While Hongkongers have been known to move to places such as Taiwan and Canada, an increasing number of people have in recent weeks started considering less traditional locations – like Portugal.

Some are trying to obtain Portuguese nationality through their family ties in Macau, while others are considering getting citizenship by making investments, perceiving the country as a gateway to Europe.

Given that the environment in Hong Kong is not very promising … we want to have another choice if things go very bad here.

SECOND HOME

Cheung, a recent retiree, first thought of buying property in Portugal last year, after a family trip there. But her intentions have grown stronger of late, and she even started to consider living there.

“We really liked the place, so previously I thought about it as a sort of ‘flex’ holiday home. Many British people go there just for the weekend,” the 57-year-old woman says. “But given the current situation in Hong Kong, this has become more of a priority and I am considering whether we should move there.”

Cheung’s two children live in England and she now views Portugal as an affordable place where her family could eventually be reunited.

Her friend Lai, a 56-year-old secondary-school teacher, also began thinking of moving out of Hong Kong as the political and social crisis deepened.

“Given that the environment in Hong Kong is not very promising … we want to have another choice if things go very bad here,” says Lai, who also only gave her surname.

She joined some of the recent protests and is worried that her hometown will not remain a beacon of freedom of expression for much longer.

According to unofficial estimates, more than 20 demonstrations were held in the past three months, and over 4 million people marched against the extradition bill, which would allow criminal suspects to be sent to jurisdictions the city does not have any extradition agreement with, including mainland China.

Such actions have morphed into wider demands for democracy in Hong Kong – a Chinese-ruled territory that enjoys a high degree of autonomy, but with no universal suffrage in the election of its leader.

“I am really thinking of moving to Portugal, mostly because of my children [aged 17 and 24]. If they have another citizenship, they can get a job more easily in Europe,” Lai says. “To be honest, it’s a safety issue.”

THE PROMISE OF PORTUGAL

Lai and Cheung were among about 50 people who attended an information session this month about moving to Portugal through making investments, organised by the John Hu Migration Consulting agency in Hong Kong.

In a packed room, many of those present raised queries on the difficulty of learning Portuguese – because it is necessary to pass an exam to become a national – and the length of time applicants needed to spend in the country before being permitted to apply for a passport.

The sun-drenched European nation of 10.3 million people, once in the economic doldrums, is experiencing a tourism boom, with travellers drawn by its cultural appeal and pristine beaches. In recent years, thousands of foreigners have also made investments and moved there.

Yung, a 37-year-old businesswoman, and her husband are among those looking into such options. “We know that Hong Kong is part of China, but we were told we could keep our rights for 50 years under the ‘one country, two systems’ principle. Unfortunately, it does not look like that will happen,” she says. “We are thinking of moving to a country with democracy, so our children can enjoy real freedom.”

Hong Kong is a former British colony that was handed over to China in 1997 with the promise that the city would retain freedoms not enjoyed in the mainland until at least 2047 – such as an independent legal system, press freedom and the right to protest.

Yung, whose children are aged three and five, says the family is not planning to move immediately. “But we want to prepare for the future.”

If they decide to make Portugal their home, the whole family will tag along, including her parents and her husband’s relatives, she says.

His father was born in neighbouring Macau – a former Portuguese colony – and he has permanent residency there.

Yung says they are trying to obtain nationality through this family connection, but if they can’t they will likely follow the investment path.

Lam, the data expert, is in a similar situation. The 28-year-old, whose father was born in Macau and held a passport, started making queries last week on the legal requirements to obtain Portuguese citizenship.

Lam says her intention to leave comes from multiple political concerns.

“It’s been just 20 years after the handover, and they have already started doing things that make people feel insecure,” she says.

Some people also view with suspicion infrastructure projects that serve to boost regional integration, such as the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and the high-speed railway, which now connects the city to the mainland.

“I am concerned that more [mainland] Chinese will come to Hong Kong. Their presence may benefit the retail sector, but it’s impacting our lives,” Lam says.

She also fears that initiatives pioneered in the mainland, such as the “social credit system” – aimed at assessing the social and economic reputation of citizens – could be introduced in Hong Kong in the near future, despite recent denials by the government.

Lam, who married less than a year ago and is considering having children, says that apart from rights concerns, Hong Kong’s high property prices, decreasing quality of life and education system are factors contributing to her decision.

“Our education here is too focused on academic achievements … Many officials send their children abroad,” she says. “If they had confidence in our system, they wouldn’t do it, right?”

Lam believes that by being Portuguese citizens, her future children would receive a more progressive and affordable education at a European school.

Europe would also be a “good retirement plan” for her and her husband, she says.

Lam, who is from a working-class background, says migration has become a common topic of conversation among her friends.

“Many people I know, who are relatively well educated, not very wealthy but with some money, will migrate. Some have talked about Taiwan and Thailand,” she says. “We are all shaken by this uncertainty and instability.”

The lack of confidence expressed by such Hongkongers will not go away any time soon, according to political commentator Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who last month wrote that “the political wounds left by this saga cannot be easily healed”.

A Macau-based lawyer who has assisted Hong Kong residents seeking a new life in Portugal says it is no surprise people are “trying to come up with a backup plan”.

“I don’t think it’s because of the extradition bill alone. They fear what the future may hold,” says the lawyer, who declined to be named.

‘LIKE BUYING INSURANCE’

For agencies such as John Hu Migration Consulting, business is booming.

“Portugal is becoming popular,” says founder John Hu. “Over the past few years, the requirements for mainstream countries, such as Australia, Canada and Britain, have become harder and harder, so other European countries have become more attractive for Hong Kong residents.”

Several EU nations, such as Malta and Bulgaria, run similar residence-by-investment schemes.

Hu says his agency has received double the number of queries in the past month.

“In the past, people would make some enquiries and take months before making a decision, but now because of … the political situation in Hong Kong, people have become more determined,” he says. “For many, it’s like buying insurance – in case something happens in Hong Kong, they have somewhere to go and live permanently.”

William Tonnard, a French businessman who worked as a banker in Hong Kong before moving to Portugal five years ago to set up a real estate firm, visited the city last week to cater to the fresh demand.

There has been “a clear increase in the interest from Hong Kong investors mainly in the [Portuguese] real estate sector” in the wake of the recent political upheaval, says the president and chief operating officer at OptylonKrea.

Tonnard names tax incentives and the high quality of living as the top reasons for Portugal’s appeal, which has led many foreign nationals to move there to set up businesses, live and retire.

RENEWED CONFIDENCE

After a series of financial crises, Portugal in 2015 began to experience an upswing as the government dropped austerity measures.

The move, which occurred alongside an overall strong recovery in the region, brought about renewed business and consumer confidence, and tourists also started pouring into the nation.

Lisbon, the capital, has been especially energised. Dozens of hotels, shops and restaurants have opened their doors as some 4.5 million visitors pass through the city annually. The tourism boom has helped to dramatically reduce unemployment, while other industries have also grown in recent years.

Lisbon has been labelled as a “rising tech hub”, with dozens of foreign-owned start-ups emerging. Top international companies such as Google, Bosch, Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz have also recently opened offices and digital research centres in the city and surrounding areas.

Investment in Portugal’s export-oriented industrial, services and technology sectors hit a record high in 2017, when the economy grew 2.7 per cent, its fastest rate in 17 years.

Although growth is now slowing and local residents have blamed foreign investment for increasingly high housing rents, especially in Lisbon, Tonnard says the outlook is still positive.

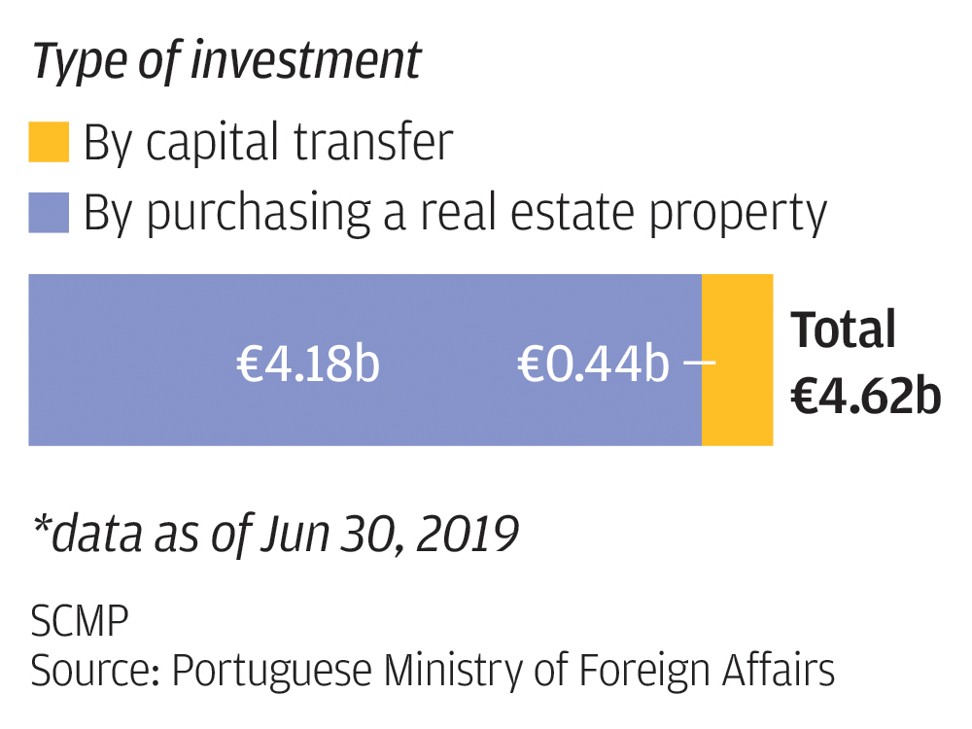

The Golden Visa programme, introduced in 2012, has also played a significant role in luring new investors. By June, Portugal had issued 7,583 such permits – accounting for a total of €4.62 billion (US$5.19 billion) in incoming investments for the country – most of which were approved based on property purchases worth a minimum of €500,000. On top of that, 12,874 residence permits were given to family members.

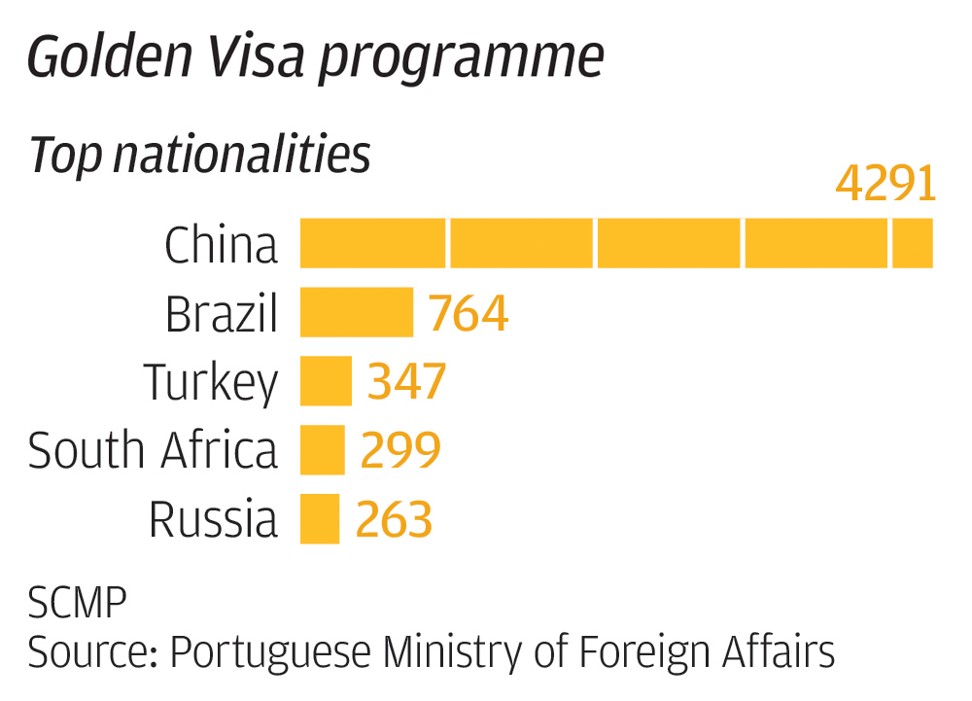

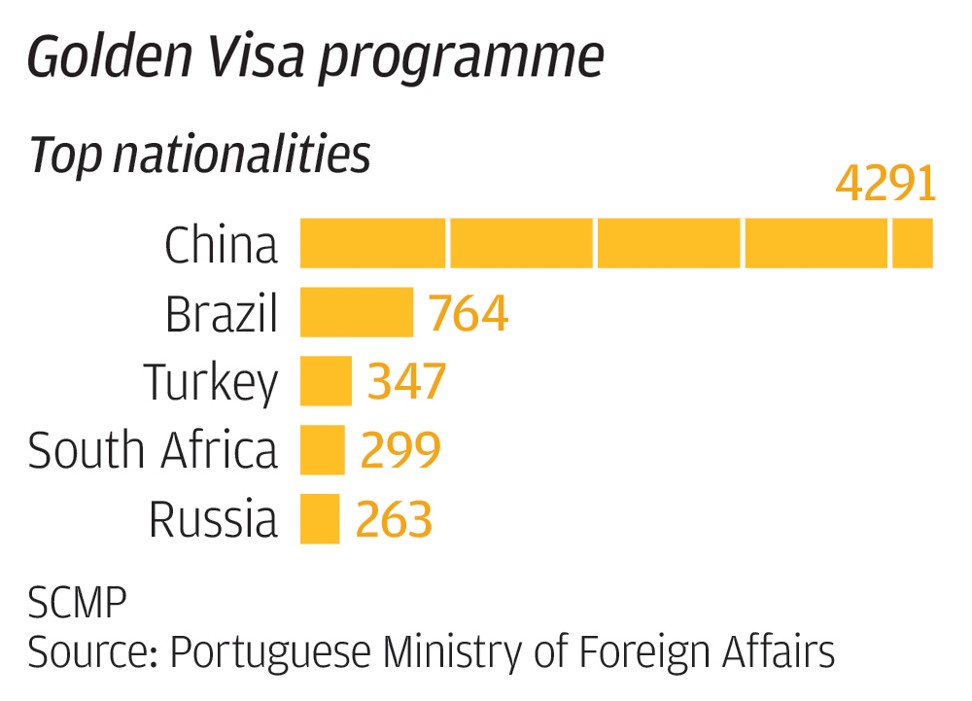

Chinese citizens have led the list of nationals acquiring a Golden Visa permit. From October 2012 to this Junethe scheme approved the applications of 4,291 Chinese investors – representing 57 per cent of the total pool of successful applicants.

Chinese citizens have led the list of nationals acquiring a Golden Visa permit. From October 2012 to this Junethe scheme approved the applications of 4,291 Chinese investors – representing 57 per cent of the total pool of successful applicants.“We know that among these investors, some come from Hong Kong,” says Luis Lima, head of the Portuguese Real Estate Agents Association. “Many look for the safety and stability an investment in real estate in Portugal offers. They are usually interested in a safe place that works well as a business platform with Europe.”

While acquiring residency elsewhere or migrating is a pragmatic decision for many, Lam says hers stems from anguish.

“I am heartbroken because it’s sad to see what is happening in Hong Kong … And the main problem is that our government officials claim they are open, but they have shown no sincerity,” she says.

“Who knows when the Chinese government will apply the same rules [as in the mainland] here?

“I don’t even dare to imagine.”

- Previous Hong Kong unrest fuels negative image of China among Japanese

- Next Inside the world’s biggest Yazidi temple in Armenia