The relentless assault on Hazaras continues. What can be done to stop it?

The Hazara community of Quetta ended its sit-in on Monday night after receiving assurances from Balochistan Chief Minister Jam Kamal Alyani and State Minister for Interior Sheharyar Afridi.

They had been protesting against the Hazarganji bombing that claimed 20 lives, including eight members of the Hazara community.

Although ethnic Baloch and Pashtuns were also killed in the bombing, the Hazara community was the main target of the suicide attack.

The ethnic/sectarian cleansing of Hazaras has been going on for at least a decade. Targeted killings, suicide attacks and bomb blasts have inflicted harm to daily life, education and business activities of the roughly half a million Hazaras living in Quetta.

Shops run by members of the Hazara community once populated shopping centres and malls in Liaqat Bazaar and along Abdul Sattar Road and Jinnah Road.

Relentless assaults, however, have forced these shopkeepers to abandon their businesses and sell their properties.

With the exodus of Hazaras, shopping centres have become increasingly desolate and ethnically-homogenous places, bereft of the kaleidoscopic beauty that once made them the busiest part of the city.

A relentless assault

The most important cause of the relentless assault on Hazaras is the inadequate response and ineffective strategy of the state.

Despite the initiation of the National Action Plan, sectarian militant groups continue to operate in Balochistan.

Over the past few years, the footprint of the militant Islamic State group, which has joined hands with Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan and sectarian groups, has increased in the province.

Moreover, the state has failed to bring perpetrators of sectarian violenceto justice. Repeated attacks on Hazaras have gone unpunished. The First Information Reports are almost always lodged against unknown persons.

Pakistan’s domestic policy has been found wanting as far countering terrorism is concerned. We stand accused of pursuing a policy that distinguishes between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ terrorists.

There is a perception that the state doesn’t have a zero-tolerance policy for violence perpetrated by certain non-state actors.

This has created confusion and uncertainty on strategic and tactical levels and has been duly exploited by non-state actors.

In addition, we have repeatedly been accused of becoming a party to the Saudi-Iran proxy war.

Analysts and political pundits in Balochistan fear that the recently-announced Saudi investments in Gwadar and Reko Diq may turn the province into a battleground for a regional proxy war.

Hazaras suspect that the presence of Saudis in Balochistan might intensify their persecution.

Increasing ghettoisation

The most worrisome aspect of this crisis is the isolation of the Hazara community, which has been hounded into virtual ghettos in two Hazara neighbourhoods on opposite sides of Quetta: Marriabad and Hazara Town.

This restricted movement has created economic hardships and affected access to basic health and education services. The entire economic activity of the community is now confined to these two areas, causing severe losses.

Most importantly, forced ghettoisation has curtailed the presence and participation of members of the Hazara community in civic organisations and spaces in the city — thus reducing opportunities of interaction between Hazaras and other communities.

For instance: it is a shame that I have visited Marriabad and Hazara Town each only once over the past two years. On both occasions, I went there to attend a sit-in organised by Jalila Haider and her supporters.

Sit-ins and protests have become the only occasions when a tiny number of progressive activists from other communities get to visit Hazara-populated areas. The worst bit is that even ghettos haven’t ensured security for Hazaras.

Enforced ghettoisation and isolation has produced negative outcomes not only in the present but are also likely to impede the long-term integration of Hazaras in Quetta.

Academic research suggests that increased civic engagement between different groups in multi-ethnic societies curtails inter-group tension and conflict.

Ashutosh Varshney, the author of Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life, argues that greater interaction and civic ties between members of different ethnic groups decrease the likelihood of conflict. Strong associational forms of civic engagement are more likely to foster inter-group harmony.

Although Varshney’s findings are based on communal violence in India, they do have some relevance for a multi-ethnic city like Quetta.

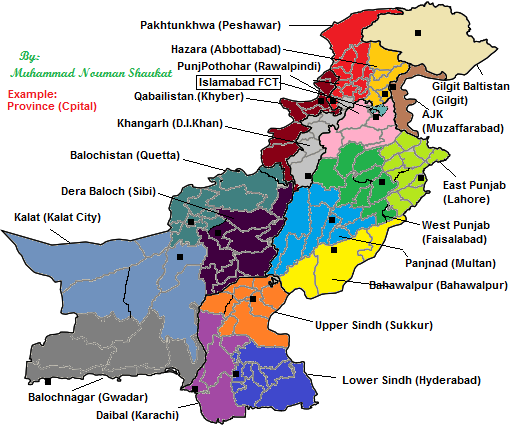

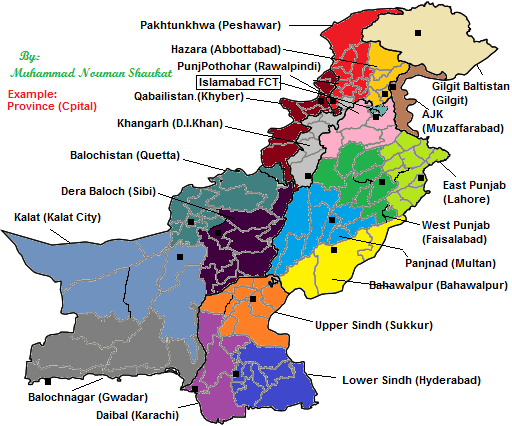

Quetta is arguably one of the most polarised and ethnically-divided cities of Pakistan. The fact that major ethnic groups (Baloch, Pashtun and Hazaras) are geographically concentrated and segregated has played a huge role in facilitating and reinforcing the ethnic divide.

Inter-ethnic civic spaces are too few and too weak. Political parties and civic organisations such as traders’ associations, student bodies, chambers of commerce, literary societies and professional associations have increasingly become ethnically homogenous.

Nearly all political parties, including ethnic and non-ethnic parties, in the city are organised primarily along ethnic — and to some extent tribal — lines.

Consequently, there are very few inter-ethnic civic platforms that can promote harmony and manage tensions between different communities.

Transcending boundaries

The lack of robust inter-ethnic civic and political organisations has affected the Hazara community the most.

While Pashtuns and Baloch too have faced oppression at the hands of the state and non-state actors, they, on account of a bigger population and greater territorial control in comparison to Hazaras, are better equipped to withstand oppression and launch an organised resistance movement.

In contrast, the Hazara community, owing to its small size and limited territory, lacks the critical mass required to exert meaningful pressure and influence on state policies.

While improved security measures and a shift in internal and foreign policy are a must for ensuring durable peace in Balochistan, it is also time that all communities of Quetta join hands to wage a united political struggle.

Progressive activists like Jalila Haider and Tahir Hazara are leading the way by building alliances with other communities. A multi-ethnic city like Quetta desperately needs a political party whose appeal transcends ethnic, sectarian and religious identity.

- Previous U.N. envoy sees troop withdrawal in Yemen’s Hodeidah within weeks

- Next WHERE SHOULD HAZARAS GO?