The traps and lures of Kolkata’s dance bars

In March and April 2015, Kolkata police raided the dance bars along VIP Road, the headquarters of the sprawling nightlife business of a man named Jagjit Singh. On April 12, Singh and an estimated 60 men stormed the local police station. He was accused of assaulting Sukomal Das, the station’s inspector-in-charge. Over the course of his career, Singh has been charged with attempted murder, causing grievous harm with a dangerous weapon, and abetment.

He stayed effectively untouched. Downtown Group of Companies, the corporation Singh runs, plausibly claims to operate the largest chain of restaurants and bars in West Bengal. Its website names 20 establishments, including hotels, food courts, and bars. Yet the police have reckoned that Singh owns 50 bars alone. One source said that Singh directly or indirectly controls 60% of the dance bars in Baguiati, a developing neighborhood near the Kolkata airport that has four-to-six dozen of them. Singh’s company takes its name from its first business, Hotel Downtown, which is said by some to have been Kolkata’s original dance bar.

That designation would surprise many Kolkatans. Affluent Bengalis in the city tend not to know that Kolkata has dance bars, assuming the lurid tales of Mumbai’s infamous dance bars are foreign elements of the crasser north and west sections of India. Even local experts in sex work say that dance bars are rare or new. In fact, Kolkata has become a regional capital of dance bars over the last decade. It’s hard to imagine there being more dance bars in any other city in India.

Until recently, this combination of invisibility and influence also characterized Jagjit Singh. Though little known, his power extended beyond the world of nightlife. Sulil Mukhopadhyay, the chief financial officer of Downtown, told me that the company hoped to enter into other industries, such as “foreign liquor bottling”, and to “achieve the five-star hotel”. Singh’s son Gursimran has often hosted indie music concerts popular with Kolkata’s well-to-do youth. The concerts may not have been as profitable as the rest of the Singh family’s business, but the events had another motive. “He wanted to create another image of himself,” said a source knowledgeable about the local music scene.

The Singh family’s social success kept pace with the success of their business. Honey Singh performed at the wedding of Jagjit’s other son, Keerat. Actors Diljit Dosanjh and Koel Mallick also attended. Jagjit is pictured on Facebook at Gursimran’s bar Beer Republic smiling with Stephane Amalir, the prominent director of the Alliance Française du Bengale, and Amalir’s wife, Laura. Still, I could not find anybody in Kolkata willing to discuss the Singh family in detail on the record. The world of dance bars is sufficiently dangerous that most people I spoke to requested anonymity out of fear for their safety.

This March, the comfortable obscurity shrouding the Singh family was lifted. On the night of the 12th, a brawl between gangs at Shimmers, a lounge owned by Downtown and used by Gursimran and Keerat for after-parties, drew the attention of the police. They arrested the bar’s two managers, Paritosh Banerjee and Swarup Ghosh, for keeping Shimmers open later than the law allows. Banerjee and Ghosh’s testimony indicated that Singh had directed them to keep the bar open late, facilitate the escape of the fighters, and hide the episode from the police. Singh was arrested in Delhi, where police say he was about to abscond to Singapore. He is being held without bail. Human trafficking charges have been added to the crimes he is accused of, and police are arresting his associates.

Jagjit Singh’s influence on Kolkata remains. A source of both insecurity and independence for performers, and of big money for people in the business, Kolkata’s dance bars are also a ritualized and spectacular and entrancing form of entertainment for men across the city. These gathering places of educated women without opportunity, eccentric activists, mafia dons, and petty criminals display the misery and also the allure of Kolkata’s long decay.

“WE HAVEN’T SEEN MUCH”

Dance bars originated in and around Mumbai in the 1980s. They were widely romanticized and deplored through 2005, when the Maharashtra state government issued a ban. Some 75,000 dancers lost their jobs. At around the same time, Kolkata bar owners started hiding something. The pleasant and quiet bars of Chandni Chowk, the historic business district, suddenly built stages, installed lights, and hired female performers. The proprietors told the local press of a surge in “popular demand” for “live entertainment”. A more likely explanation is the exodus from Mumbai. Varsha Kale, the honorary president of the Bharatiya Bar Girls’ Union, said in an interview that 13 thousand Mumbai bar girls were from Kolkata and that most returned to Bengal.

The Kolkata bars have continued to do everything possible to avoid being called ‘dance bars’, a label Mumbai made disreputable. The signs they post outside might only advertise “live singing”. Many identify themselves as a “bar and restaurant” and nothing more. Others simply say they are a “family restaurant” until a certain hour of the evening.

The most that employees tend to say is that they work at a “singing bar”, asserting that there isn’t any dancing going on even if it is happening in a room directly behind them. I was given these clearly false denials at Esplanade Bar and Restaurant, Night Queen’s, and Chung Wah, among other establishments. Talking to a different employee at Esplanade one night, the whole point was made clear to me in case the dancing was too subtle. “Aapkho cash hei, layna girls” (you have cash, you take girls), he said in broken Hindi.

Kolkata’s dance bars are in neighbourhoods throughout the city, but they are often packed closely together: in a four-block radius of the Chandni Chowk metro stop, there are 12. In Baguiati and nearby Rajarhat, almost every “bar” is a dance bar. They are both ubiquitous and hidden.

This inconspicuousness makes for a stark contrast with Kolkata’s red-light districts, especially Sonagachi, which has been the subject of an Oscar-winning documentary titled Born into Brothels. In these places, sustained public scrutiny has helped attract local and foreign NGOs that combat trafficking and the sexual exploitation of underage women. Yet even employees of these groups do not seem knowledgeable about or interested in the world of dance bars. Souvik Basu, a program coordinator at Sanlaap, which focuses on the destructive consequences of sex work, told me flatly that “there are not many dance bars in Kolkata,” adding, “There might be, but we haven’t seen much.”

Beer, coloured lights, a stripper pole — a characteristic scene at a Kolkata dance bar. (Picture courtesy/Rajeev Sarkar)

Representatives of the International Justice Mission, which has similar goals to Sanlaap, argued that dance bars tend not to employ underage girls, not to keep dancers on their premises by force, and to benefit only indirectly from trafficking, making them fall outside the organization’s purview. Dolphy Biswas, the IJM manager for government relations, said that, in Sonagachi, women work much longer hours, make much less money, engage in much more sex work, and enjoy much less control over their lives than bar dancers.

Sources among dancers, activists, and the police agreed that many dancers are relatively better off but also said that some dance bars are owned by traffickers. “Those which belong to Jagjit Singh, those which belong to Ajmal Siddiqui — those are related with human trafficking,” said Arka Banerjee, the subdivisional police officer of Baruipur. Banerjee used to be the assistant commissioner of the Bidhannagar City Police, a district that includes Baguiati and Rajarhat. Banerjee himself conducted raids on dance bars and helped gather testimony from dancers about how they had received appealing job offers in other states and moved to Bengal only to be forced into dance bars and sex work.

One dancer, whom I will call Abhranila, told me that trafficking is common. “Most girls arrive [at dance bars] through agents. Because they leave their cities and come here, they don’t know anything about the place.” These “agents,” she added, frequently torture girls in the “initial days”. “In the end you have to adjust,” Abhranila said repeatedly. She estimated that as many as nine in ten bar girls had been abandoned by their husbands.

In some respects, dance bars tend to follow the law carefully. Assignations between customers and dancers are arranged by notes written on napkins, which are ferried by ‘floor boys’ from the audience to the women onstage. The notes usually result in a customer’s or a dancer’s cell phone number. A deal is struck through WhatsApp without official involvement from the bar and without an obvious act of solicitation, which is illegal. The bars also abide by some of the regulations formulated for them by the Calcutta High Court. In accordance with court orders, they have erected roughly three-foot-high railings around the stage; they separate the stage and the audience by about four feet; and they forbid stripping and physical contact with dancers.

Other High Court regulations, such as mandatory metal detectors and a ban on pole dancing, were widely ignored at the dance bars I visited. More fundamentally, dance bars must be certified by licenses that do not necessarily allow dancing, for which special permission may be necessary. Even then, to abide by the Indian Penal Code, the dancing cannot be “obscene”. This criterion, however vague it might seem, is clearly unfulfilled by dance bars such as Esplanade, where women provocatively thrust their waists and protrude their breasts on a skinny stage in a tiny, dark room.

The enforcement of these regulations is inconstant. Multiple sources I spoke to raised concerns about an ill-conceived division of labour between the police and excise department, as well as the possibility of bias. “Police will act on the violation of law and order,” one cop told me, “but the excise has the specific duty to control or regulate those dance bars … Excise was not so helpful, and they are not thinking in the same manner.”

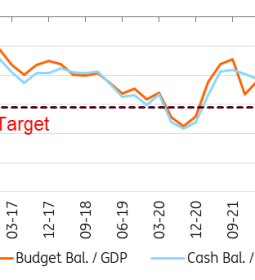

In 2015, the collector of excise in North-24 Parganas and the additional magistrate of the district sought, unsuccessfully, to ban dance bars in the area of the Bidhannagar commissionerate. Nonetheless, it is a paradox that the West Bengal excise department must monitor dance bars while also depending on their continued existence. The state government’s crushing debt is currently approaching double its projected revenue. The percentage of tax intake that comes from alcohol, meanwhile, has substantially increased. It was 8.3 per cent in 2014-2015, and it is projected to be 9.25 per cent in 2016-2017.

The administration is taking an active part in this growth. Last year, it reduced the number of dry days from 12 to four, extended bar hours, and allowed bars to function as liquor stores. Officials see alcohol as such an important source of potential revenue that, in January, West Bengal set up a state-owned alcohol distribution business.

Kolkata’s dance bars have thus managed to evade serious and effective resistance, with one possible exception.

“YOU WILL HAVE TO TAKE LIFE RISKS”

Rajeev Sarkar is not quite 40 years old, a bachelor with a neat moustache and closely cropped hair. He walks around with his arms full of loose-leaf sheets, battered manila folders, and labeled notebooks. He conscientiously sends his acquaintances articles about local misdeeds, videos of inappropriate behaviour or abuse, and official documents related to legal work done by India’s Smile, the NGO that he founded. One document Sarkar shared with me had gone through enough bureaucrats and lawyers to acquire six different signatures and nine separate stamps.

His investigations, legal actions, and moral passions range widely. He has launched, with some success, public interest litigation regarding the illegal circulation of coupons and fake coins, abuses in fertility clinics, and the unavailability of government documents involving Subhas Chandra Bose. He once provided legal aid and, he said, money for rent to Suzette Jordan, the victim of the infamous Park Street rape. He has worked to protect local forests and water bodies. He has encouraged and frequently helped cause police action against corrupt officials in the Bose Institute, public transportation, and the Indian Museum.

We met, twice, at the apartment of Rajat Muhuri, the 24-year-old secretary trustee of India’s Smile and Sarkar’s apprentice and disciple. Sitting on Muhuri’s bed with a plate of rasogalla and sandesh between us, Sarkar spoke calmly but emphatically about Kolkata’s dance bars. His clandestine research and legal advocacy have been a powerful check on dance bars.

Rajeev Sarkar, an expert on dance bars, describing the crime and exploitation he says he has found at them. (Samir Jana/HT PHOTO)

In contrast to the representatives of Sanlaap and IJM, Sarkar told me that he finds dance bars a more pressing social and moral problem than red light districts. Dance bars, some of which are in residential areas, play loud music and cause scenes on the street that interrupt the lives of local people and change the character of their neighbourhoods, Sarkar said. While Sonagachi is infamous, the subject of movies and the main focus of many NGOs and researchers, dance bars are often ignored by community leaders and are little understood by the upper classes. Yet in essence, said Sarkar, they ply the same trade: “In singing bars they sing, and in dance bars they dance to the music that is played. This is the only difference; but the backdrop is the same. The real thing is prostitution and women trafficking.”

Before the raids that provoked Jagjit Singh to incite a mob, Kolkata’s dance bars were mostly free from supervision. Based on information he had received about trafficking and prostitution, Sarkar started investigating in March 2015. “When we entered, the system of the dance bar was such that … well, you could say [the girls were] half naked; that’s how they danced. Money used to float like this,” he said, waving his arms. Using an app on his phone that allowed him to take photographs surreptitiously, Sarkar sent pictures to Arka Banerjee, who went on his first raid later that night. The High Court issued its regulations a few months later.

In some ways, Kolkata’s dance bars were forced to change. The nudity and the lap dances witnessed by Sarkar came to an end. There was an infamous ‘rain-dance’ that used to happen at Jagjit Singh’s bar Sunset in which a girl would have to dance in a sari under a stream of water privately for customers. That too has been stopped. Sarkar ceased going to dance bars himself — every waiter has seen a photograph of him, he said — but he continued fighting the injustices of dance bars in other ways, for example by using data on missing persons to try to piece together information on traffickers. He said he had sent the police information about 50 potential agents. He has continued to alert both local police and central anti-corruption forces about specific bars that are breaking the law.

The system, however, has stayed fundamentally intact. Jagjit Singh continued operating his empire from Downtown’s large offices on VIP Road. A few bars were shut down, but most adapted to a few new rules and carried on.

Four months after Sarkar started surveying dance bars, he and Muhuri were beaten by men wielding iron rods and bricks. Last August, men on motorcycles passed by Sarkar swinging iron rods at his head. As a result of these attacks, Sarkar’s face is pocked with scars, and he is unable to lift anything heavy with his right hand. “There is a reason why they wanted to kill me,” he said. “I had hit at the entire system.” Sarkar says that he eventually received 24-hour police protection as a result.

Sarkar concluded that many authorities deliberately ignore criminal activity at dance bars. When he tries to file right-to-information requests, he is often forced to withdraw them after receiving threats. Officials seem to be leaking information to the dance bars. “This whole thing is a nexus,” he said. “Politicians, the police, the administration.” If the lack of scrutiny directed at dance bars is not the result of a conspiracy, then it is caused by fear. Many activists want to legalize much about the business of Sonagachi; dance bars, on the other hand, “are entirely a criminal belt,” Sarkar said. “You will have to take life risks if you enter.” Later I would learn how deeply these risks had affected him.

EARNING AND SPENDING

It’s hard to tell whether most dancers are freely choosing their line of work. I met Abhranila and her boyfriend at Muhuri’s apartment along with him and Sarkar. She described lacking opportunities throughout her life but also took some pride in working at dance bars and in the independence they afforded her. She had no immediate plans to seek an alternative.

Now 24, she is from a large city in Bengal. She graduated from college with honours and a political science degree. She hoped to attend RICE Institute, a popular vocational coaching program, but was forbidden to do so by her father, who felt a daughter of his being “out” in such a manner would be unseemly. Just a month after graduation, Abhranila found herself running away from home, to Kolkata.

On the way, she called one of her few friends from college living in the city. Having left a job at a call centre that specialized in scamming Americans, he was now running the music at a dance bar. He gave her the number of a ‘bandleader’, the title given to the person who rents out the stage of a dance bar and organizes the women and the music. The bandleader arranged to have someone pick up Abhranila at the bus station when she arrived in Kolkata.

“Initially I didn’t like it at all. I just cried on the floor,” said Abhranila. Eventually, she adjusted, as she said all dancers do. Abhranila gave a glimpse of how this process of reconciliation might work. Characterizing an archetypal woman who danced professionally at weddings, and was tricked into moving to Kolkata to perform at dance bars, she said, “She might find it impossible to dance in front of these people. The women who dance there realize what they have to do after seeing it. She might feel bad for a few days—but then she might start to think, ‘I am kind of doing the same thing. I used to dance in front of people back there, and I am doing the same now.’ This is what it’s about.”

Now Abhranila and her boyfriend — the friend who first introduced her to dance bars, a 28-year-old old I will call Subhadeep — generally praise dance bars. In spite of the dubious maneouvers of traffickers, the process of, as she said, “adjustment,” and evidence of forced labour brought to her attention during our interview by Sarkar, Abhranila still said that it is rare for dancers to work under compulsion. At bars, dancers make considerably more money than they could anywhere else. Until their savings were spent on a sudden medical problem, Abhranila and Subhadeep had saved 15 lakhs. Dancers choose between two financial arrangements: either being “on the fifty”, meaning they receive half the tips given to them by the audience, or being on salary, which is around Rs 2,000 per night for a successful dancer, Abhranila said.

She and Subhadeep speak reverently about the high yields some dancers occasionally make. “Large collections are especially made on birthdays, or Valentine’s Day, or the 31st,” said Abhranila. Well-liked dancers “easily make three or four lakhs. Two lakhs is pretty standard.” “Some girls celebrate their birthday three times a year,” added Subhadeep with a smirk.

These staggering tips sometimes transform into something much more. “Many of them marry their customers,” said Abhranila said of her fellow dancers. Does this happen mainly with rich clients? Abhranila observed: “Not always. Love happens too.” She was more uncertain, and at times self-contradictory, about the frequency of prostitution. At first, she repeatedly said that many dancers engage in sex work. Later in our conversation, however, she said that only “one or two very needy people among forty would,” and added that “it might even be only one. Only if they really need the money.”

Some customers, however, see dance bars as a way to find a better sort of hooker. I spent two nights with a man I will call Samir who’d been going to dance bars regularly for three years. A 30 year old with a pudgy face and a receding hairline, he was wearing an orange polo shirt with a popped collar and skinny jeans. He relished the opportunity to speak about the inner workings of dance bars. Samir said that he often spends Rs 4,000 or more in tips to get a dancer’s attention. “20-30 thousand is a good deal,” he said of paying for sex. “You have to pay a lot up front to show that you’re serious.”

All this money might be for naught; usually, according to Samir, dancers sleep with customers only at their own discretion. But bar owners are not entirely disinterested. “You’ll find hardly any singing bars that only make money on singing,” said Samir. “They make money on the girls.” Samir contributes to this economy in multiple ways. In addition to attending the bars a few nights a week, he said he also made monthly payments of $2,000 to a woman in Sonagachi who was seven months pregnant with his child. Besides her, he said that he had a girlfriend he met at Rocks, a dance bar in Chandni Chowk. Still, one day, he texted me, “i am taking a girl out in a hotel … Will send her pic to you … She is a teenager … Hardly 16 years”.

Samir funds his exploits at dance bars and with women through a website design business in which, he said, he paid local coders a small fraction of commissions worth hundreds of US dollars. Though his company has a Facebook page updated as recently as February, I was unable to reach its website, whose domain name had apparently expired on April 9. Sometimes, Samir proudly declared he would take care of all expenses in nighttime expeditions that he said would cost Rs 10,000; at other moments, he would refer vaguely to his “outstandings”, and say there were places he could not visit.

THE MAN WITH SNAKES IN HIS POCKETS

Few people in the enigmatic world of dance bars are free from the occasional self-contradictions of Abhranila and Samir, the divisions between public and private live evident in Jagjit Singh. On Saturday, as the print version of this article was going to press, the deputy commissioner of the detective department of the Bidhannagar Police, Santosh Pandey, who is leading the investigation into Jagjit Singh, contacted me with bewildering news. In the last week, Pandey said, the Kolkata police had found payments from Downtown to India’s Smile beginning in October 2015 and extending until the time of Jagjit Singh’s arrest. They amounted to lakhs of rupees. Sarkar was now part of the investigation into Singh.

Had Sarkar been enveloped into the very “nexus” he inveighed against? I relayed Pandey’s information to Sarkar, and received a disquieting reply.

Now Sarkar told a story not so much of perseverance as of woe. Over a year ago, he had been filing PILs about dance bars in the hope they might get banned. On May 20, 2016, the Calcutta High Court told him simply to express his concerns to the local police. Given how little Sarkar trusted the police, this news was crushing. He told me that he officially left India’s Smile a few days later — a bizarre revelation, since Sarkar continues to control the official India’s Smile email address; to receive billing on its website as the “chief functionary officer”; and to refer to it in conversation as “my NGO”. An article in The Times of India from just last month described him as a member. Two months ago I spoke to Abhay Chawdhary, the President Trustee of the group, about Sarkar’s current involvement.

At the same time as his PIL ended and he said he quit India’s Smile, Sarkar got a call from Jagjit Singh asking if he would be willing to help Downtown “rectify the illegalities” Sarkar had discovered at its bars. Singh offered Sarkar Rs 25,000 per month as a consultant. Sarkar accepted. He said he sometimes notified Singh of the violations he observed but doesn’t remember how often. Singh, who Sarkar said had also provided another India’s Smile affiliate with a loan in October 2015, began funding the organization.

Sarkar had many justifications for this seemingly discrediting decision. He said that a “good relationship” with Singh helped him collect information about trafficking; that he had not been dissuaded from continuing to report Singh’s bars to the police; that he was frightened of another attack; and that he had no other source of income: “Personal help is another issue. That is humanitarian ground.” Both his parents, he added, are sick and need money. Finally, the alternative of continuing to resist the power of the great dance bar magnate had begun to seem pointless. “Actually, Jagjit Singh Purchased police and Administration and Political persons,” he wrote me on WhatsApp. “Result is I was going to frustration and along still.”

The fates of Singh and Sarkar, who became business partners of a sort, have grown entwined. As Singh languishes in prison, Sarkar says he has lost his 24-hour police protection, which he told me ended on May 7 without any advance notice or explanation. He thinks that he could be killed at any time. Singh seems not to have been Sarkar’s only potential threat: the second attack against him occurred months after he had gone on Singh’s payroll.

Sarkar has been in danger before. When he was 28, he testified as a witness in a murder trial despite threats that dissuaded other witnesses from involvement in the case. Sarkar described this episode of moral courage as formative of his devotion to the pursuit of justice. But Muhuri suggested that Sarkar is also motivated by a certain unconventionality and oddness. “He used to bring snakes to school in his pockets,” said the young man. “It’s quite natural that a guy like him would want to hit the dance bar system.”

ENJOY YOURSELF, OR ELSE

The ambiguity I found everywhere in my research into dance bars is representative of the experience of an average night at one of them. They are designed to put a bargoer into a daze or a trance. The music pulses and thumps loudly enough to render conversation impossible. To talk at all, it is necessary to scream into your interlocutor’s ear, creating the impression, from afar, that everyone is whispering. Two, three, four, even five disco balls whirl above the stage, showering the room with flashing, multicolored lights. Smoking inside is universally permitted, but the windows are boarded up such that cigarette fumes form a kind of permanent fog.

All this creates a kind of sensory overload, an addled feeling in which the world of mundane concerns outside the bar and its dancers falls away. As in a theatre, the stage is at the front of the room, with all other objects positioned as much as possible in its direction. The dancers often wear shiny medals, sequins, or glitter. They dance to and sing all sorts of music — Western hits, such as Sia’s “Cheap Thrills”, and songs by artists such as Honey Singh and occasionally old Bollywood and Bengali tunes — but all of it evokes romance or sex. In this environment, exposed midriffs or arms or feet are capable of provoking rapt attention.

Dancers and customers are clearly communicating, but not in a way that is legible to anyone else. Napkins with concealed messages dart back and forth. The men and women engage in ‘eye-talking’, a term used to describe the way a dancer holds a customer’s gaze to show interest, or looks up or out to indicate places they might go to meet alone. The most frequent form of exchange are tips, which, like napkins, are usually couriered by floor boys. They throw the money over the dancer’s head, so it rains down on her as she dances, or hand over individual bills intently. They always make sure to point out the customer who gave the tip. His presence has, in a way, penetrated the otherwise remote world of the stage.

As Samir and Abhranila each said, not all women will go home with a customer, making their gestures and expressions into a riddle for the men in the audience to drunkenly interpret. While one or more women dance on stage, others sit and wait on a couch behind them, in view of the audience but technically no longer performing. Perhaps they stare into their phones — to make deals with customers, or simply to distract themselves? Perhaps they talk among themselves and giggle and seem to look at you — incidentally, or portentously?

Sitting in the crowd, it is not always clear what even the most dogged clients are seeking. Over the course of one night at Glo Bar, a dance bar off a highway in North Kolkata, a portly middle-aged man continually gave the same woman in a blue dress 100 rupee notes one by one. Each time, a floor boy brought the money all the way from the man’s table in the back of the bar up to the stage. Waiters would also take messages from him both to the DJ, who would put on a Hindi song at his request, and to the woman in the blue, who would dance solo to the music he had chosen. Was he suggesting his interest in a rendezvous later, or was he enacting his fantasy right there in the dance bar?

The uncertainties and incongruities and self-enclosure of dance bars, and the fears and appetites they provoke, resemble nothing so much as a dream. The names of dance bars reflect this otherworldliness: Mercury, Venus, Galaxy, Glo, Night Queen’s, Golden Inn. The juxtapositions in the old design of the first-floor of Night Queen’s distinguished it as the most surreal dance bar. Drab, cheap furnishings sat below framed prints of the classic paintings “The Mona Lisa” and Pierre-Auguste Cot’s “The Storm”; women spun and swayed atop a stage that had a narrow aquarium around its perimeter, such that the droopy fish nearly bumped into each other going through the cloudy water of their cramped passageway.

In the midst of these strange visions, some men seem to reach a kind of ecstasy. They stand up in their chair, pound the table in front of them, clap and wiggle and gesticulate, cigarette in hand, a drink and a fat stack of bills in arm’s reach. Others embrace, hold each other’s faces, and loudly sing along to favourite songs together.

Not everyone can escape themselves so easily. At Chung Wah, a stubbly 25-year-old named Chandradeep told me how he’d come because his girlfriend had just broken up with him. He was drunk enough to ask me twice where I was from. Like many dance bar customers, Chandradeep was sitting alone.

The transporting effects of a night at a dance bar sometimes prove irresistible. “There are some people who can’t do without dance bars,” said Abhranila. “Yes, every day. It’s an addiction.” “It happens,” chimed in Sarkar; “many people go bankrupt from visiting dance bars.” “Way too many!” exclaimed Abhranila. Even her boyfriend, who works at a dance bar, goes to them for fun. When I asked Subhadeep if he rains money on dancers when he goes out, he demurred; this led Abhranila to chuckle. “No matter what he says, everyone feels intoxicated in that environment … He must have thrown, but he isn’t saying it in my presence.”

Abhranila said that many dancers are not immune to the dreamlike quality of dance bars. “It’s quite adventurous for us too. We had called people of our fathers’ age ‘uncle’ till now, and suddenly we are calling them ‘jaanu’ (darling). That’s quite an adventure, isn’t it!” The allure of dance bars is not, for Abhranila, limited to the dancer’s point of view. “There’s so much glamour,” she said. “What you get to see at the dance bars for those four or five hours, you won’t get to see anywhere else.” If, for some reason, the music temporarily stops at a dance bar, a pointed awkwardness descends on everyone inside. It is like a spell has been broken.

I used to live in Kolkata, and when I left my office in Chandni Chowk at night, I heard the plaintive singing, and saw the neon lights, and wondered what happened inside. Like other young men, I was drawn to dance bars out of a murky curiosity. During most of my visits to them, fellow patrons like Samir or Chandradeep seemed happy to see me, a foreigner, drinking where they drank and watching what they watched.

At other times, however, my presence aroused the darker forces that lurk behind dance bars. After I sat down with a friend at one of the dance bars inside Kingston Hotel, owned by Jagjit Singh, men at the bar started throwing peanuts at our heads. When I would turn around and look at the crowd assembled there, they would only stare in return. One emissary came to our table, asking us to give him Rs 2000 to be distributed among the women as tips. We refused. Another man approached, and we questioned him about the bar snacks flying in our direction. “I’m sorry for that,” he said, and continued in a manner that was jolly and foreboding at the same time, both offering the opportunity for pleasure and suggesting the issuance of a threat. “If you enjoy yourselves,” he announced, “we’ll all enjoy ourselves.”

- Previous Triple talaq undesirable, practitioners to face boycott: Muslim board to SC The affidavit, filed by AIMPLB in the SC, also speaks of excluding the provision of triple talaq from the nikahnamas (marriage contracts).

- Next Israeli, Indian Firms Ink $630 Million Missile Defense Deal