Trump calls for mass deportations. This Indian state is already weeding out undocumented Muslims.

HATIMURIA, India — Eight years ago, a dozen families showed up at this quiet farming village, saying floodwaters had washed away their homes.

They spoke with a different accent, and the villagers wondered if they might be illegal Muslim immigrants who had crossed the porous border from neighboring Bangladesh. Illegal immigration has been a contentious issue in this northeastern state of Assam for over three decades.

Yet “we pitied them and gave them refuge,” said Lavanya Bisaya, the 56-year-old mother of the village headman.

But as the newcomers’ numbers swelled to 200 families, tensions began to mount, until finally villagers were protesting and chanting, “Liberate our land, remove outsiders!” echoing a debate raging across Assam.

As Donald Trump has pledged to throw out up to 3 million undocumented immigrants from the United States, this remote Indian state of 31 million is in the midst of an effort of its own to identify and “weed out” some of the more than 20 million illegal immigrants from Bangladesh living in India.

Officials launched a laborious effort to certify the Bangladeshi population in India two years ago, but the drive that has been infused with new vigor and cash since the governing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party won state elections in April.

“The Hindu rate of population growth is declining. But the Muslim rate is rising. Most of the Muslims here are from Bangladesh. If this continues, the Assamese Hindus will become a minority soon; we will lose our language, our culture, our identity,” said Himanta Biswa Sarma, finance minister in the Assam government.

Fears that terrorist groups with global backing from neighboring Bangladesh would cross over the border to radicalize local youths have also galvanized the effort, officials say.

“Our detect-delete-deport campaign is even more important because now Islamic extremist groups from Bangladesh are also sending their people to India along with the immigrants on this route,” said Samujjal Bhattacharya, a longtime activist.

Muslim-majority Bangladesh fought for independence from Pakistan and became an independent nation in 1971. Assam’s border with Bangladesh stretches for about 160 miles, 40 percent of it through wetlands, making it relatively easy for poor Bangladeshis looking for work in India to cross over. Anger over their presence in India dates to the 1980s, when the state endured six years of anti-immigration agitation that spawned armed guerrilla groups.

As public rhetoric against the immigrants has soared, activists fear that declaring hundreds of thousands of people here illegally may whip up anti-Muslim sentiment and leave India with a humanitarian crisis because there is no treaty to deport them.

Detecting the illegal immigrants is not easy, either, officials say, because many of them have mingled with local populations over time, obtained forged documents, bought land and even voted.

In the past two years, officials digitized the handwritten census data of 1951 and the voter list of 1971 and created a legacy database.

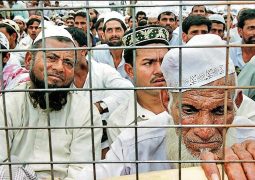

People lined up to submit over 60 million documents related to birth, land ownership and education to prove they were citizens.

But many applicants have lied and declared false connections to citizens picked out from the legacy data, officials say.

For example, 31 people have claimed to be the children of the same father. Another group of applicants have claimed the same woman as their mother — if it were true, she would have been giving birth to a new child every month.

To combat fraud, officials are now poring over family trees of two generations of each applicant to corroborate information about parents and siblings.

[It’s not easy for women to own land in India. One woman died fighting for hers.]

“The family tree corroboration is my real weapon against fraud. There is a lot of public anxiety around this exercise,” said Prateek Hajela, who heads the National Register of Citizens. “This project is like a river of fire and we have to swim in it.”

The exercise is estimated to cost $138 million and several deadlines have already been missed.

Meanwhile, people are growing impatient.

In the past year, Hatimuria village became a mini-battleground of locals versus immigrants — with street fights and tense night patrols.

Tensions worsened last month when the villagers erected a bamboo fence to block the passage of newcomers to a squatters’ settlement, and filed a police complaint. When the authorities did not act, the women locked up the police station and staged a two day sit-in.

Bowing to public pressure, the police arrived days later with an elephant and a bulldozer and mowed down the squatters’ shelters.

“There are so many of them spread all over the state; we are anxiously waiting for the government to finish its paperwork and uproot them,” said Phukan Chandra Medhi, the village elder.

But the evicted families have resettled in another vacant plot of land near the river not too far away. They say they have papers to prove they are legal.

“These days, the public mood is very negative. You have an argument with somebody on the street and they call you a Bangladeshi,” said Noor Jamal Ali, a 30-year-old tailor.

“My father was born here. How many times do I need to shout that I am a citizen?” asked Mohibul Islam Badshah, a schoolteacher.

Even though the immigrant population also includes some Hindus who entered India from Bangladesh, the sentiment against immigrants has morphed into rhetoric against Muslims, who make up about 34 percent of the state’s population.

“If indeed there are illegal immigrants, send them back. But don’t stamp the Bangladeshi tag on all Muslims so loosely,” said Aminul Islam, general secretary of the All India United Democratic Front, a political party that represents many Muslim voters.

Crossing into India is not very difficult, security officials say. It takes a few hours by boat, and there are many middlemen along the border who help find safe routes, often with the connivance of corrupt officers.

“As soon as they arrive, their priority is to enter their names into the voter list somehow. They forge all kinds of documents and pay bribes for this,” said Upamanyu Hazarika, a Supreme Court lawyer and convener of Forum Against Infiltration. His group mobilized the women in Hatimuria against the squatters.

Many of those who have been caught up in the citizenship drive who cannot prove their lineage are now languishing in detention centers.

“It is no coincidence that most people declared foreigners by the tribunals are extremely poor and illiterate, and cannot access competent lawyers,” said Aman Wadud, who provides free legal aid to “doubtful” voters.

On the day the police came to Hatimuria to evict the squatters, Bisaya and other women climbed the rocks and watched the scene from a distance.

“As a human being I felt sad seeing them run here and there, holding on to their children and things as their tin houses were crushed,” Bisaya recalled. “But we have been tolerant for too long. They stole our goats, lemons and bicycles. Tomorrow they would have stolen our jobs and land, too.”

- Previous Central Asia – Ultimate destinations to travel

- Next Demoratic and fair conditions for polls