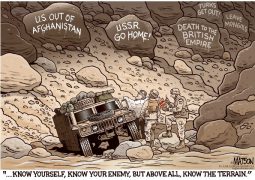

US Senate asks aswer frp the Wgite House on Afghan pullout

Lawmakers want answers from the nation’s top spy about the impact of a hasty U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Jack Detsch

At the same time, the army and his newly formed militias continued to attack Afghan villages, engendering distrust among the mujahideen who still remembered disappeared relatives and suffering in Najibullah’s dungeons.

But by bringing a measure of stability to war-wracked Afghanistan, Najibullah burnished part of his legacy. Even today, many in the current Afghan government look back fondly on elements of Najibullah’s rule, and see an example to follow. Meanwhile, for all the ink that’s spilled over the atrocities committed by mujahideen and other warlords during the civil war after Najibullah’s fall from power in 1992, the crimes of the Afghan communist regimes in Kabul are often whitewashed or downplayed by regime supporters or by younger generations who recall only Najibullah’s heartfelt, charismatic speeches still available on YouTube.

“Afghans who look back on the days of Najibullah as a time of peace have conveniently forgotten the thousands who were tortured and killed by secret police under his command. Was he willing to make peace at the end? Possibly. But if he was, we gain nothing by erasing the lives of those who suffered because of his part in the war,” Patricia Gossman, associate Asia director for Human Rights Watch, told Foreign Policy.

Najibullah’s complicated legacy explains the controversy over Mohib’s graveside visit, which many observers understood as a deliberate political message. A quarter-century after his death, Najibullah still has a strong base in the country’s southeast, a Pashtun heartland; in Afghanistan, the dead cast a long shadow. Afghanistan’s bloody past is again present as the country grapples with a solution to decades of conflict.

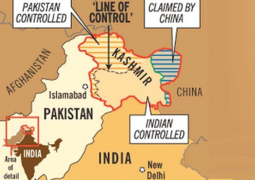

“Mohib wants to be politically successful, so he believes he needs Najibullah’s Pashtun nationalist supporters, who have become very loud during the last years,” said Sayed Jalal Shajjan, a Kabul-based anthropologist and writer. The visit was a reminder of Taliban brutality and a poke in the eye to Pakistan, a country whose intelligence services have long supported Taliban insurgents and a frequent target of Mohib’s verbal barbs.

But Mohib apparently sought to hedge his bets with his Eid visits, paying homage as well to the grave of Ahmad Shah Massoud, a legendary commander of the mujahideen known as the “Lion of the Panjshir,” who fought first the Soviets (and Najibullah) then the Taliban, before he was killed by assassins linked to al Qaeda two days before the 9/11 attacks.

“Mohib did not do this without calculation,” said Shajjan. “He is preparing himself to become the next president, the leader of a new generation of Afghans. And to be successful with that, he visited the graves of both Massoud and Najibullah, two very contrary figures.”

Afghanistan’s bloody past—and especially the role played by the Taliban after a period of civil war—is again present as the country grapples with a solution to decades of conflict. When the Taliban, after years of fighting, finally entered Kabul in 1996, they broke into the compound where Najibullah had spent four years in hiding, brutally tortured and murdered him, then hung his mutilated corpse out on public display.

Today, with the prospect of the Taliban returning to Kabul and taking a part in the new government, many have déjà vu. Like Najibullah, current President Ashraf Ghani comes from the Pashtun Ahmadzai tribe, prominent in the southeast. And like Najibullah, Ghani, who finds himself in an isolated situation between Washington and the Taliban, hopes to arouse nationalist and patriotic feelings among his Pashtun supporters to protect himself from Taliban reprisals. Although it appears very unlikely at the moment, some Afghans even fear that Ghani will eventually share a similar violent fate after the Americans withdraw and the Taliban reconquer Kabul.

Ghani nodded back at the dissolution of the republic and the bloody fate of Najibullah—perhaps as a cautionary tale for Afghanistan’s road ahead.

“Najibullah made the mistake of his life by announcing that he was going to resign,” Ghani said. “Please don’t ask us to replay a film that we know well.”

Emran Feroz is a freelance journalist, author, and the founder of Drone Memorial, a virtual memorial for civilian drone strike victims

- Previous As Foreign Superpower Exits Afghanistan, Insurgent Fault Lines Deepen

- Next Turkey vs Egypt in Lybia: Egypt’s threats on Libya ‘irrational bluff’ to keep Haftar at negotiating table