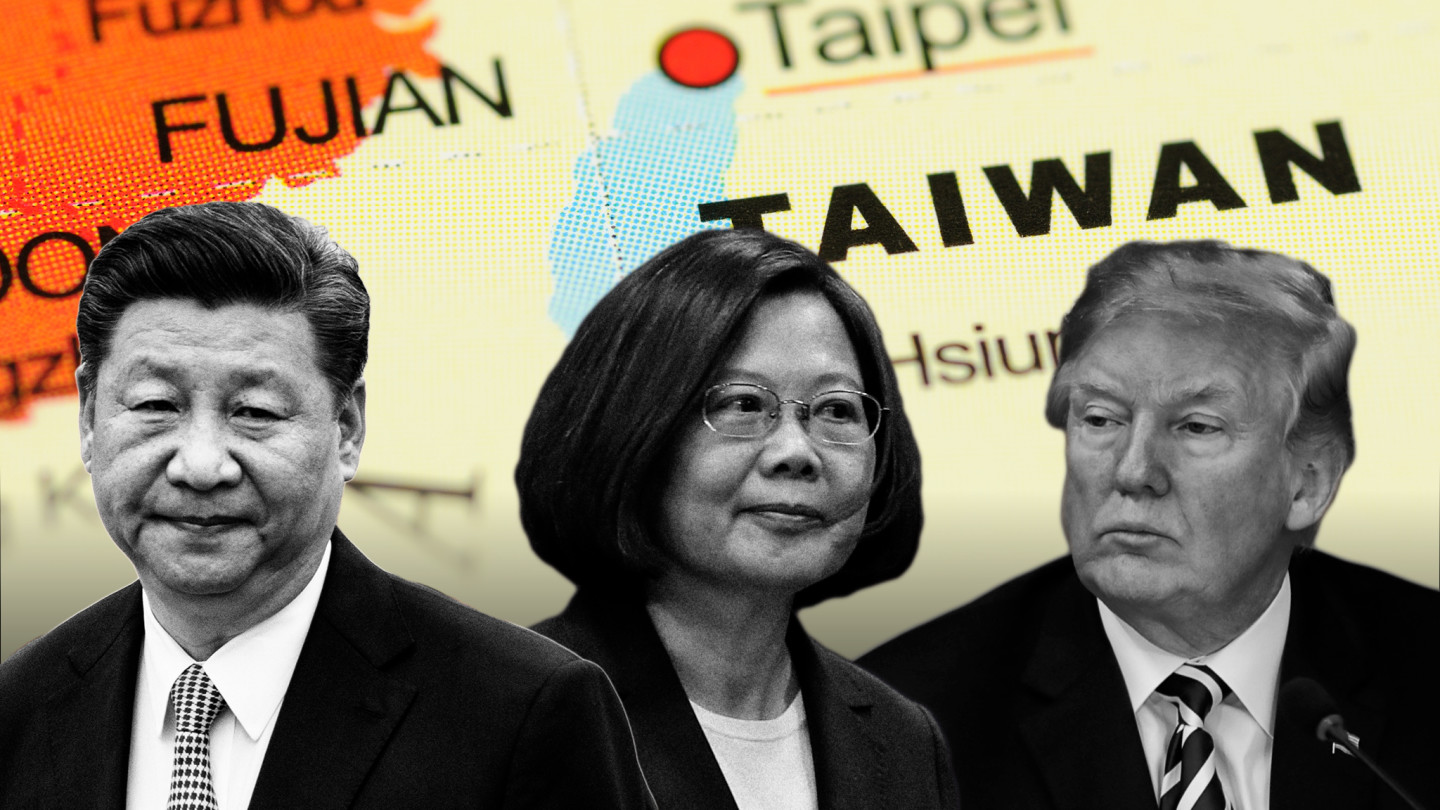

US warships and PLA jets: what’s really behind the Taiwan Strait provocations between China and the US

of the Taiwan Strait and, despite repeated warnings from Taipei’s military, flew 43 nautical miles into Taiwan’s airspace. This was the first such crossing in nearly two decades.

between Beijing and the US over the regime for passage of warships and warplanes through the strait. This controversy has potentially dangerous practical implications.

The median line has existed since 1955 when it was declared by General Benjamin Davis, then the commander of the US 13th Air Force based in Taipei, as part of the “rules of engagement”. There was no formal agreement and Beijing has not officially recognised it because, in its view, Taiwan is an inalienable part of its territory. Nevertheless, the median line has in practice served to separate the two sides and their military activities.

as well.

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, all ships and aircraft enjoy the right of transit passage in straits used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone, and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone. Transit passage is the exercise of the freedom of navigation and overflight solely for the purpose of continuous and expeditious transit.

that “if the strait is formed by an island of a state bordering the strait and its mainland, transit passage shall not apply if there exists seaward of the island a route through the high seas or through an exclusive economic zone of similar convenience”.

, it claims that all the waters in the strait are under China’s jurisdiction and comprise its internal waters, territorial seas and its exclusive economic zone.

The US Navy claims that the waters in the strait are “international”. The then commander of US Pacific Command, Admiral Timothy Keating, said during an official visit to China in 2008: “We don’t need China’s permission to go through the Taiwan Strait. It’s international waters. We will exercise our free right of passage whenever and wherever we choose, as we have done repeatedly in the past and we’ll do in the future.”

However, there is no such legal regime as “international waters”. Apparently, what the US legally claims is high seas freedom of navigation and overflight for all vessels, including military vessels and aircraft, through the strait’s exclusive economic zone, regardless of whether it is Beijing’s or Taipei’s. To it, such freedom of navigation and overflight also includes related activities such as anchoring; the launching and recovery of aircraft and water craft; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance activities; and exercises and manoeuvres.

between their warships in the South China Sea. Indeed, the stepped-up US warship transits of the strait – about once a month since October 2018, from one a year at most in the past – can be interpreted as a demonstration of this claim, and Beijing’s provocative crossing of the median line can be considered a response thereto.

But in addition to arguing that warships should use the Luzon Strait instead of the Taiwan Strait, Beijing also claims certain restrictions on the activities of warships in its exclusive economic zone, including that in the strait. In practice, this US-China dispute boils down to whether China can set conditions for the passage of vessels through its exclusive economic zone in the strait. While these differences have yet to come to the fore there, they have resulted in international incidents elsewhere in Beijing’s claimed exclusive economic zones.

These differences are, again, based on different interpretations of the relevant provisions of the Law of the Sea, which the US has not ratified. Despite the US position to the contrary, the Law of the Sea exclusive economic zone regime does have some restrictions on freedom of navigation, such as the duty to pay “due regard” to the rights of the coastal state, including not violating its marine scientific research consent and environmental protection regimes or threatening its security.

Other Law of the Sea terms that pertain to freedom of navigation in the exclusive economic zone – and whose meaning is disputed – include “abuse of rights”, “peaceful use/purpose”, “marine scientific research”, and “other internationally lawful uses of the sea”.

China is not alone in its interpretation that there are limits to freedom of navigation in exclusive economic zones. Some 17 other states also claim some restrictions on military activities in their exclusive economic zones, including, in Asia, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan and US ally Thailand. They further argue that the Law of the Sea was a “package deal” and that non-ratifiers of the treaty like the US cannot credibly or legitimately pick and choose which treaty provisions they wish to abide by and unilaterally interpret them to their benefit.

Tensions in the Taiwan Strait – between Beijing and Taipei, and between Beijing and Washington – are clearly on the boil and are being driven by a myriad of factors. But the creeping confrontation of contrasting interpretations of the applicable navigation regime for military vessels and aircraft in the strait could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior fellow at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China

- Previous Don’t Rejoin the Iran Deal, Fix It

- Next ‘Let’s copy Malaysia’: fake news stokes fears for Chinese Indonesians