WHY ARE MIDDLE CLASS CHINESE MOVING THEIR MONEY ABROAD? Homes in Thailand, insurance in Hong Kong – investors have many ways to skirt the rules and send their savings overseas, leaving Beijing with a growing headache in its war on capital flight

Coco Lui

The view from Guo Lili’s condo will be worth the years of saving she has put in to afford this tiny slice of the Thai capital. From her one-bedroom flat on the 33rd floor, she will have a sweeping view of Bangkok that stretches to the horizon. Her decision to buy in one of the Thai capital’s most popular residential areas, On Nut, is part of a long-term vision for Guo, who sees the property as a solid investment. The flat is under construction and she will not get the key until 2019, but when that moment comes she will have access to everything from a private swimming pool to the street-level restaurants many floors below serving up fresh, authentic Pad Thai. Until then, it is a safe place to park her money.

Magnificent though the view is – Guo knows because she sent up a drone up to take pictures – she is hesitant to show it off too much – understandable, perhaps, given she had to bend some rules to buy here. As a Chinese citizen, Guo is barred from sending money abroad to buy property. Yet, unfortunately for Beijing and its efforts to stem increasing flows of money from leaving the Chinese economy, individual investors like Guo are finding it easy to get around such restrictions. In her case, all it took was a couple of fibs and a willing accomplice. And Guo is far from alone.

CAPITAL FLIGHT

Middle-class investors such as Guo represent the latest front in Beijing’s battle to stem the capital outflows from its economy that last year hit US$640 billion dollars – up from US$118 billion in 2014, according to the Washington-based global association the Institute of International Finance. While Beijing has long been concerned with the efforts of its super rich to move money abroad, the rise of China’s rapidly expanding middle class has put overseas investment within the grasp of a vast new body of people – middle-class workers numbered 200 million people in 2015, accounting for a total wealth of US$28.3 trillion, according to Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

What the interior of Guo’s flat will look like when it is completed in 2019. Photo: Supplied

And concerns over China’s economic outlook and a recent weakening of the yuan that saw the currency fall nearly 7 per cent against the US dollar in 2016 are encouraging ever greater numbers to channel their hard-earned savings abroad, just like Guo.

While capital outflows are an essential part of global trade – when a Chinese teenager buys a second-hand drone from a New Yorker on eBay, for example, he is sending money out of China – too much money going overseas too quickly can hamper a country’s economic stability.

Smog in Beijing. Gloom over the domestic economy is prompting many middle class to invest abroad, skirting official restrictions.

This is why Beijing has stepped in with a raft of measures in recent months to restrict the flow of Chinese money overseas. Businesses, for example, have been banned from making overseas investments of more than US$10 billion and forbidden from mergers and acquisitions worth more than US$1 billion, while state-run firms have been barred from foreign real estate deals involving more than US$1 billion.

Australia first: what new visa policy means for Chinese, Asian immigrants

Crucially, some of these measures have also been aimed at the middle class. While Chinese citizens have long been barred from sending money abroad to buy property or engage in other forms of investment, Beijing has turned a blind eye to that rule in the past, enforcing it only since late last year. Beijing allows its citizens to purchase up to US$50,000 dollars in foreign currency a year, but there are persistent rumours – denied by regulators – that China will lower this amount to just US$10,000 per person. In October, state-backed UnionPay, China’s largest bank-card provider, banned customers from purchasing overseas insurance products other than accident, illness and tourism-related policies, to block another popular avenue for those seeking to spirit their money out of the country. UnionPay followed up that move in March by barring clients on the Chinese mainland from using its services to pay for Hong Kong property. From July 1, Chinese banks will have to report customers who deposit or withdraw cash in foreign currency worth US$10,000 in a day.

People walk past a branch of China Minsheng Bank in Beijing. From July 1, Chinese banks will have to report customers who deposit, withdraw or transfer foreign currency worth US$10,000 in a day. Photo: Reuters

While investments such as Guo’s may seem small fry – consider, for example, that Chinese appliance producer Midea’s takeover of German robotics maker KUKA alone sent out nearly US$5 billion last year – the enormity of the Chinese middle class means that taken collectively, such investments stack up.

As Christopher Balding, an associate professor at Peking University HSBC Business School, says: “When even a small number of people in China do something, this can be a big problem. This is especially true of capital outflows.”

WHY WORRY?

Fuelling the fears of many middle-class Chinese are a variety of concerns regarding the national economy.

“I’m worried about China’s housing bubble,” said Yue Nu, an independent financial writer in Beijing, who says buying property abroad makes “perfect sense”.

“During the 2008 financial crisis, property prices slumped worldwide, but not in China. I’m concerned that China’s real estate market could collapse soon, bringing down the whole economy with it.”

A pedestrian near Jianwai Soho, a mixed-use residential and commercial complex, in Beijing, China. Many are worried China’s real estate market could collapse. Photo: Bloomberg

Despite cooling measures by authorities, in March, prices of new homes in 70 Chinese cities rose 11.3 per cent compared with a year ago, down only slightly from the 11.8 per cent gain registered in February, based on a weighted average from Reuters using data from China’s National Statistics Bureau.

Yue also fears further devaluation of the yuan, whose fall last year was its largest since 1994 when China devalued the currency by 33 per cent overnight – to 8.7 to the dollar – as part of its foreign exchange system reforms.

New Silk Road: Why China should be wary of overconfidence

“With the yuan devaluing, the sense among many people in China is that if we don’t buy overseas property right now, we will not be able to afford it in the future,” Yue said.

So Yue paid US$23,200 last year as a deposit for a studio in downtown Bangkok. “Many Chinese are doing the same thing,” she said. “The place where I bought my studio has long been known as a Japanese neighbourhood. But now, half of new apartments there are owned by Chinese.”

Of course, not every Chinese buyer of offshore property is motivated by purely economic reasons. Middle-class parents hoping to give their children a better college education may seek property in the United States; gay couples may want to settle down in open-minded Thailand.

Even so, economics plays a major role. “Worries about a weakening of the yuan against the US dollar and fears about a sharp slowdown in China’s economy were major drivers behind capital outflow from China last year,” said Chang Liu, a China analyst at London-based consultancy Capital Economics.

To shake off concerns about the yuan, Beijing sold roughly US$320 billion of its foreign exchange reserves last year, according to the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, primarily to defend the value of the currency.

Chinese gays are often attracted to invest in open-minded Thailand. Photo: AFP

But even for those Chinese who have been reassured by such measures, there are other reasons to look abroad. “I’m confident about China’s economic outlook but I don’t have a way to invest in the country,” said Chang Xiaosuo, a designer in Beijing. He had tried to buy an apartment for investment purposes, but was blocked from doing so by local authority restrictions regarding second homes. Though Chang could engage in Chinese stock markets and futures trading, those options seemed “too risky”, he said.

The result? He wired US$24,600 to Bangkok earlier this year as a deposit for a flat.

HOW THEY GET IT OUT

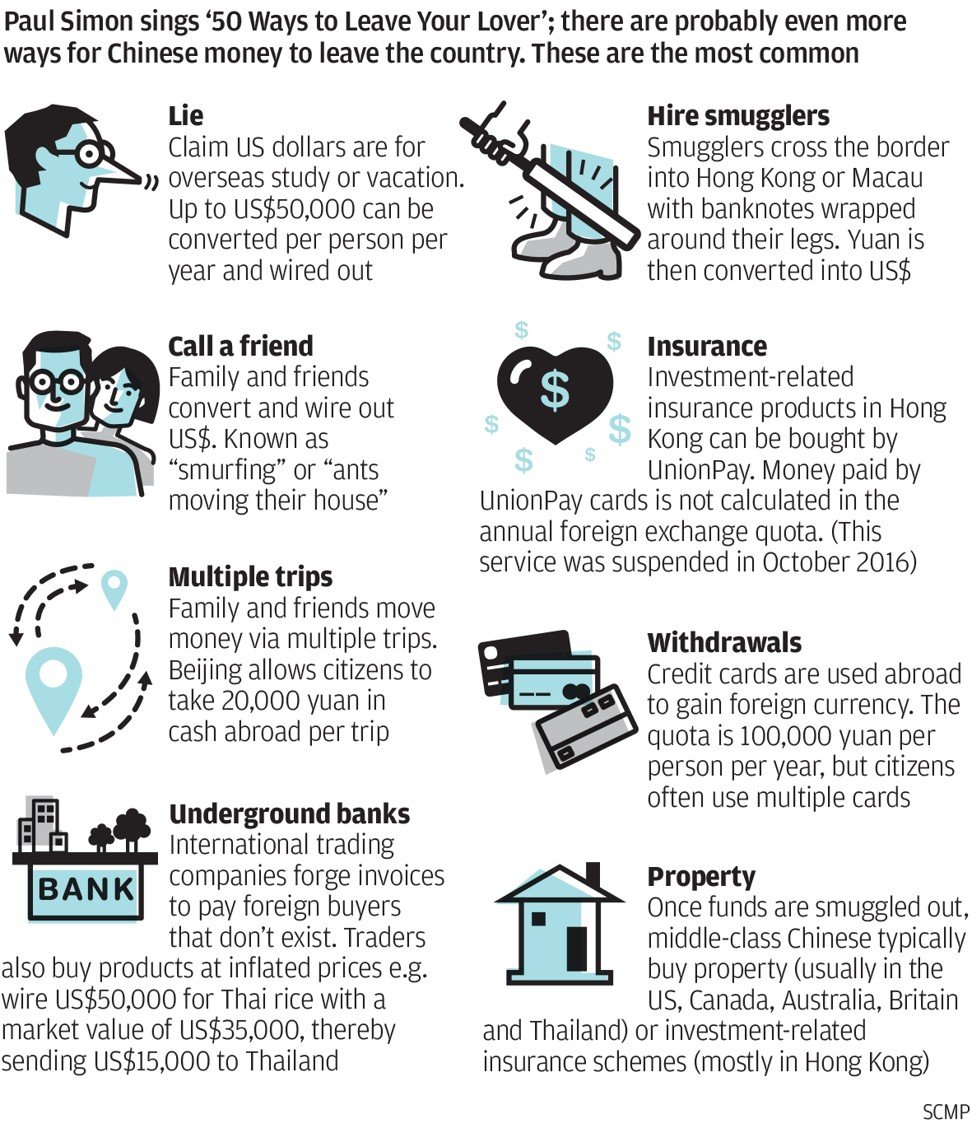

Yue, Chang and many other Chinese told This Week in Asia they got their money out of China simply by lying.

Beijing allows citizens to purchase up to US$50,000 in foreign currency each year for uses such as overseas holidays and studying abroad – common excuses used by those seeking to invest overseas.

On paper, Chinese citizens now face additional disclosure requirements when buying foreign exchange. But in practice, many banks in China – buried in paperwork and reluctant to upset clients – do little to check how the money will be used.

‘Ignore the hubris: China will get old before it gets rich’

Things get only a little more difficult for Chinese trying to exchange more than US$50,000 per year.

Some turn to underground banks or other, even more dubious options. For a small fee, there are men in Shenzhen who will wrap as many banknotes as possible around their legs and smuggle the money into neighbouring Hong Kong, which operates under a different economic system to mainland China and does not restrict currency exchange.

Beijing allows citizens to purchase up to US$50,000 in foreign currency each year for uses such as overseas holidays and studying abroad.

Others rely on friends and relatives to convert their money into US dollars and wire their money out – a process called “smurfing” in the banking industry, or “ants moving their house” in Chinese.

Chinese regulators are aware of these tricks and have tried to close the loops. This year, Shenzhen police seized 50 billion yuan (US$7 billion) in a raid on an underground bank.

The State Administration of Foreign Exchange said in December it would blacklist anyone who helped others transfer money. Possible penalties include a two-year suspension of currency exchange services and a fine of up to 30 per cent of the transaction amount.

Why China’s mixing of regulation and politics is a recipe for financial disaster

Beijing has ordered Chinese banks to report citizens withdrawing US$50,000 or more in a week. Five transactions to the same overseas bank account in a short period will also be seen as a red flag.

Even so, such measures are far from watertight.

“We told our clients to avoid transferring exactly US$50,000; instead, they go with numbers such as US$48,000 or US$49,000,” said Yin Jie, a real estate agent in Bangkok.

This year, Yin has helped 30 Chinese transfer money out of the country to buy properties in Thailand. None have been caught by regulators.

There are some signs Beijing’s capital controls are taking effect. In one high-profile case, many middle-class Chinese investors were forced to pull out of Malaysia’s Forest City development.

But elsewhere, the shopping spree continues, particularly in places such as Thailand, where cheap housing prices make it easier to get around Beijing’s restrictions.

With middle-class Chinese opting for properties worth less than US$170,000 and paying deposits as low as 30 per cent for under-construction projects, most of his clients don’t even need the help of others to get around overseas transaction limits, Yin said.

But this is not the only option for an eager investor. Another popular avenue is investing in offshore insurance schemes, particularly in Hong Kong.

Data from Hong Kong’s Office of the Commissioner of Insurance shows premiums from mainland Chinese increased at least tenfold from 2010 to 2016 – good news for the city’s 89,000 or so insurance professionals.

During the first three quarters of 2016 alone, mainland Chinese pumped more than US$6 billion – accounting for 37 per cent of the value of all new policies – into Hong Kong’s insurance industry. The commissioner’s office did not disclose the amount that had been pumped in since October, when Beijing imposed restrictions targeting insurance-related outflows. But many industry players expect the impact of the restrictions will be minor.

“I haven’t heard of anyone having trouble selling policies to mainland Chinese,” said an insurance agent from a British firm in Hong Kong.

“Most of my clients are paying premiums of less than US$50,000 a year, so it is easy for them to get around Beijing’s restrictions,” the agent said.

Indeed, if anything, Beijing’s tightening of the noose on foreign investment may have accelerated the phenomenon, according to Yin, the real estate agent in Bangkok. “The total number of buyers from China has actually increased this year,” he said. “That’s because people are afraid the government will tighten capital controls further, making it harder to move money out of the country in the future.”

Driven by such speculation, business at Yin’s company hit a record in March when it sold more than 100 flats in Thailand in a single day, mostly to Chinese middle-class buyers, including civil servants from municipal governments.

In 2016, he said, selling 100 units within three months would have been considered an achievement.

Drizzt Cui, a Beijing-based agent who helps middle-class Chinese purchase properties in Britain and elsewhere, has witnessed similar growth.

Why talk of a Chinese-led free-trade bloc is ill-conceived fantasy

“I had some 40 clients for the whole of 2016, but by mid-April this year, I had already closed more than 20 deals,” Cui said. The 33-year-old himself recently bought a two-bedroom apartment in London for investment purposes, following his first offshore property purchase in Bangkok last year.

BEIJING’S TOUGH CHOICE

China’s troubles with capital outflow can be traced back to August 2015, when Beijing devalued the yuan almost 2 per cent against the dollar in a move that took many investors by surprise.

Beijing said the devaluation was aimed at giving market forces a bigger say in the exchange rate – something the International Monetary Fund has long called for – and portrayed the move as another step on the road to the internationalisation of the currency.

But the move spooked many investors, who took the fall as a start of a long-term trend, reasoning that the Chinese central bank wanted to devalue its currency to support a domestic economy that was decelerating faster than officially recognised.

In response, investors began seeking safe havens for their money elsewhere.

Since the 2015 devaluation, Bloomberg Intelligence estimates US$1.2 trillion has left the Chinese economy.

Capital outflow from China stood at US$640 billion last year.

There are some signs China’s subsequent measures to clamp down on capital outflows are taking effect. While capital outflow from China stood at US$640 billion last year, that was still US$8 billion lower than in 2015, thanks to Beijing’s tighter restrictions on cross-border transactions and other efforts to stabilise its economy, said Hung Tran, executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance. Tran said “a significant moderation” in the pace of outflows from China was expected this year.

Yet there is a trade-off to Beijing’s actions. The “perception that China is still heavily trying to control its capital markets” could have a “negative impact”, according to Ken Wong, an economist at Eastspring Investments, the Asian asset management arm of Prudential Corporation.

- Previous How America and China Could Stumble to War

- Next Saudi king apologises to Nawaz, other leaders for snub at US-Arab-Islamic Summit