Why doubts about China’s Belt and Road Initiative persist among its neighbours

Why doubts about China’s Belt and Road Initiative persist among its neighbours

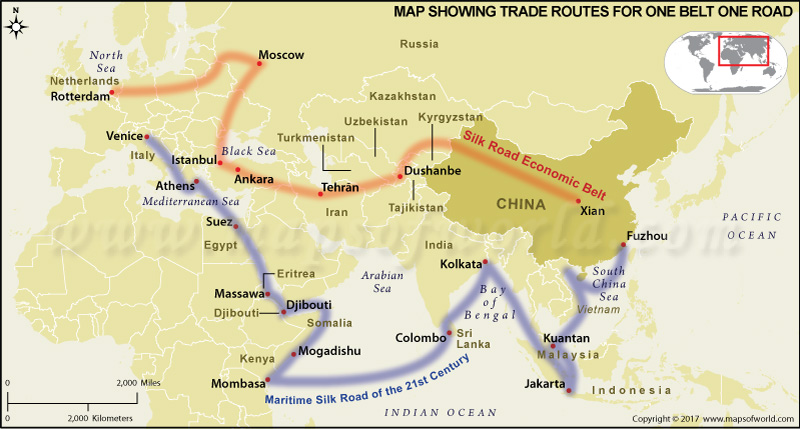

- Beijing’s global infrastructure drive will be in the spotlight this week when dozens of heads of state converge for the second Belt and Road Forum.

- In the third of a four-part series, Josephine Ma, Lee Jeong-ho and Sarah Zheng look barriers to the programme, from debt-trap fears to geopolitical rivalries

Along the banks of Nepal’s Budhigandaki River – the proposed site of a major dam – the only sign of activity on the mountainous slopes is a small office building.

So far, though, its only use has been for villagers to register for compensation for any land they might lose to the Chinese-led project.

More than six months after the government in Kathmandu recommitted to its contract with China Gezhouba Group Construction (CGGC), work on the proposed 1,200 megawatt project has stalled.

Although the newly elected government reversed the previous administration’s decision to scrap the US$2.5 billion deal back in late September, the company says it has yet to sign an official contract to start construction.

“It’s not decided properly,” a Gezhouba spokesman in Nepal said. “Although so many significant meetings [have] been held in Kathmandu between high-level CGGC people and the Nepali government, it is still waiting to be done.”

Roshan Khadka, an aide to Nepal’s Energy Minister Barsa Man Pun, also confirmed the project was “not moving” forward.

Khadka declined to reveal the reasons for the delay but analysts said the government faced pressure from opposition parties for re-awarding the contract to CGGC without a competitive bidding process, with lingering concerns over the terms of the deal.

Sunil KC, chief executive of the Asian Institute of Diplomacy and International Affairs in Kathmandu, said one problem was that the company would be responsible for all aspects of engineering, procurement, construction and finance, which requires “high financing and could create a debt burden for a country like Nepal”.

But what happened in Nepal is just one example of how China’s ambitious “Belt and Road Initiative” faces a host of difficulties – ranging from the complexities of local politics, geopolitical rivalries, fears of rising debts and commercial viability – even among neighbouring states which openly support the initiative.

Other countries have chosen to stay ambivalent as part of a balancing act between China and the United States, while India and Japan have been trying to counterbalance China’s influence in the region with their own projects.

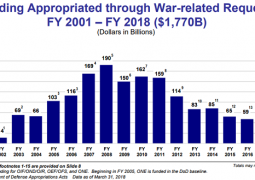

In recent years, a number of belt and road mega projects has been scaled back.

Another example is the proposed Kyaukpyu deep water port in Myanmar, where the government has asked for the price to be reviewed despite its general support for the initiative.

Even China’s close ally Pakistan is trying to reduce its borrowing from China as it faces intense pressure to restructure its immense foreign debts as it seeks a bailout from the International Monetary Fund.

Although the government has stressed it supports the belt and road plan, Railways Minister Sheikh Rasheed Ahmad said in October that the country would cut the amount it was borrowing from China to build railways from US$8.2 billion to US$6.2 billion.

Critics of the scheme said these examples showed that China’s neighbours – regardless of how friendly they were towards Beijing – were increasingly aware of the risks of a debt trap.

These concerns were highlighted after a Chinese state-owned company took over the majority stake in Hambantota port as Sri Lanka struggled to pay off its Chinese loans – a move that prompted concerns that Beijing may try to use the strategic port for military purposes even though it was a commercial contract.

“Countries are waking up to the fact that there are some negatives involved in these projects, not just positives. The Chinese loans are generally on commercial terms so projects have to be chosen carefully,” said David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s John L Thornton China Centre.

“Some proposed projects, in high-speed rail for example, are not economic. That is, the benefits and income stream will be less than the cost, including interest payments on the debt.”

Kartikeya Singh, a senior fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said: “Pakistan’s concerns on the belt and road plan are that it is a debt trap for the country, which is already reeling from the debt burden it carries and the structural changes it is required to make by the IMF.”

However, George Yeo, who was Singapore’s foreign minister between 2004 and 2011, said that while the debt trap was a real problem it would be in neither side’s interests to trigger it.

“Even if you [China] take over a port or an airport … a country can always nationalise it,” Yeo said.

He also argued that it would not always be easy for China to obtain permission to change the use of land or infrastructure in other countries.

He said that in the case of Malaysia, where former prime minister Najib Razak has been accused of large-scale corruption, these allegations might also have played a part in inflating the bills.

“Najib was very close to China, so there are many projects which were discussed, including the high-speed railway between Singapore and Malaysia,” said Yeo, who is now chairman of Kerry Logistics Network.

“Singapore also has projects with Najib’s government, now we are told that some of those projects involve corruption.”

He said it was possible that Chinese companies would also become caught up in the corruption allegations, but Mahathir, who ousted Najib, wanted to maintain good relations with Beijing and had repeatedly played up the two sides’ mutual interests.

Yeo said the countries involved in the six-year-old Belt and Road Initiative were still learning how it worked, especially when evaluating projects, and suggested that bringing in third parties could help with this process.

“I think it is still in its early days, people are learning from the successes and the mistakes,” he said.

“As China gains more experience, what it will have to do is to make sure a project is better evaluated on both sides, and bring in multinational agencies like the World Bank or AIIB,” he said, referring to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Dollar welcomed moves by countries such as Malaysia and Pakistan to adjust their belt and road plans and “scale back their ambitions to realistic levels”.

“This more practical approach is welcome,” he said. “There are certainly some good projects that can be financed through [the Belt and Road Initiative], but not on the scale originally discussed.”

Yeo also argued that geopolitical rivalry was a key factor behind the opposition to the Hambantota port project.

“There are countries, especially the United States, which find China’s rise very unsettling. It is a challenge to them,” he said.

“India is also uncomfortable because of China’s rise as it is making inroads, especially on the Indian Ocean. It is completely understandable that some of them fear that this is a strategy by China to achieve certain objectives.”

Singh from the CSIS said security concerns had put India on high alert, adding that the takeover of the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka “increases the chance of naval conflict in the Indian Ocean”.

He also said that India objected to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor passing through the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir.

“In a sense, China is giving India the right to do the same in areas that China considers part of its territory but might be in conflict with third-party nations,” Singh said.

India has already taken steps to counter China’s influence in its backyard, and Yeo cited its takeover of the loss-making Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport – once described as the “world’s emptiest airport” – in Hambantota.

“So now the port is majority owned by China and the airport is majority owned by India and each eyes the other suspiciously,” he said.

In East Asia, South Korea has remained ambivalent about the belt and road plan as it seeks to balance its relationship with China and the US.

Park Ihn-hwi, an international studies professor at Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul, said “South Korea understands that the belt and road has a strong trait of standing against America’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Also, some of its projects in certain areas – such as Central Asia – conflict with the US regional strategy.”

He argued that Seoul was concerned that the US alliances with South Korea and Japan would collide with belt and road projects and Beijing’s expansion strategy.

But Park said South Korea could afford to be ambivalent because it already had a close economic relationship with China and signing up to the initiative would have a relatively small effect on its highly developed economy.

Vietnam is trying to perform a similar balancing act between China and the US and is also reluctant to move too fast with regard to the belt and road partly because of ongoing tensions with Beijing over the South China Sea.

Although it finally signed a memorandum of understanding after two years of negotiations, Le Hong Hiep, a fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said no infrastructure projects in the country had been carried out under the belt and road branding since work began on a subway in 2011.

“Apart from some statements welcoming it and proposing principles for its implementation, Vietnam’s reactions to the initiative remain largely ambivalent because of the complex political, economic and strategic relationship between the two countries,” he said.

While Vietnam may still seek belt and road funding for a couple of relatively small-scale projects, Hiep said it was also exploring alternatives, such as loans from Japan.

The Japanese have also expressed unease about the project, even though the government has identified some economic benefits it could bring.

Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi, a visiting professor at Pusan National University in South Korea and adjunct fellow at the Pacific Forum, said Japan was concerned about the implications of joining the initiative.

“There is also a certain level of caution and uncertainty regarding it … [beyond] how it would impact Tokyo’s strategy for a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ and vice versa,” he said.

The project also threatens to undermine Japan’s economic influence.

Atsushi Tago, professor of international relations at Waseda University in Tokyo, said: “On the sphere of influence question, it will be unfortunately harmful to Japan, which used to think of itself as a key regional major power.

“The idea of the sphere of interest is inevitably a zero sum and if China expands its influence, I think it reduces one of the others,” Tago said.

But while the initiative threatens Japan’s economic influence, it can still point to some major successes in the region, such as in Bangladesh, where in 2016 the government cancelled a proposed Chinese port project in favour of a Japanese one.

Yeo argued that while Japan and the US had reasons to worry about China’s growing influence in the region, there were still opportunities for them.

“If you are Russia or Kazakhstan or Pakistan, do you want to be dependent on China alone? Of course not. In fact the closer you are with China, the more you want diversification, the more you want Americans, the Europeans, the Japanese to be there too.”

He said he liked telling the Japanese and Americans they were “free-riders” because “China has to pay for most of the infrastructure but you are welcome [to use it] for free as a friend, because all of them want diversification”.

- Previous United States under Trump is veering away from China’s belt and road

- Next In the South China Sea, Chinese fishing vessels around Thitu Island might net more than they bargained for