Why Singapore, Malaysia use kid gloves in dealing with nuclear-armed North Korea?

Even at the height of North Korea’s belligerence, Southeast Asia’s leaders have resisted the urge to join the chorus of Western voices branding Pyongyang a “pariah state”.

This softly-softly approach, Southeast Asian diplomats and foreign policy experts say, reflects a region-wide belief that dialogue – rather than tough talking – is the best way to keep the reclusive but volatile country on an even keel.

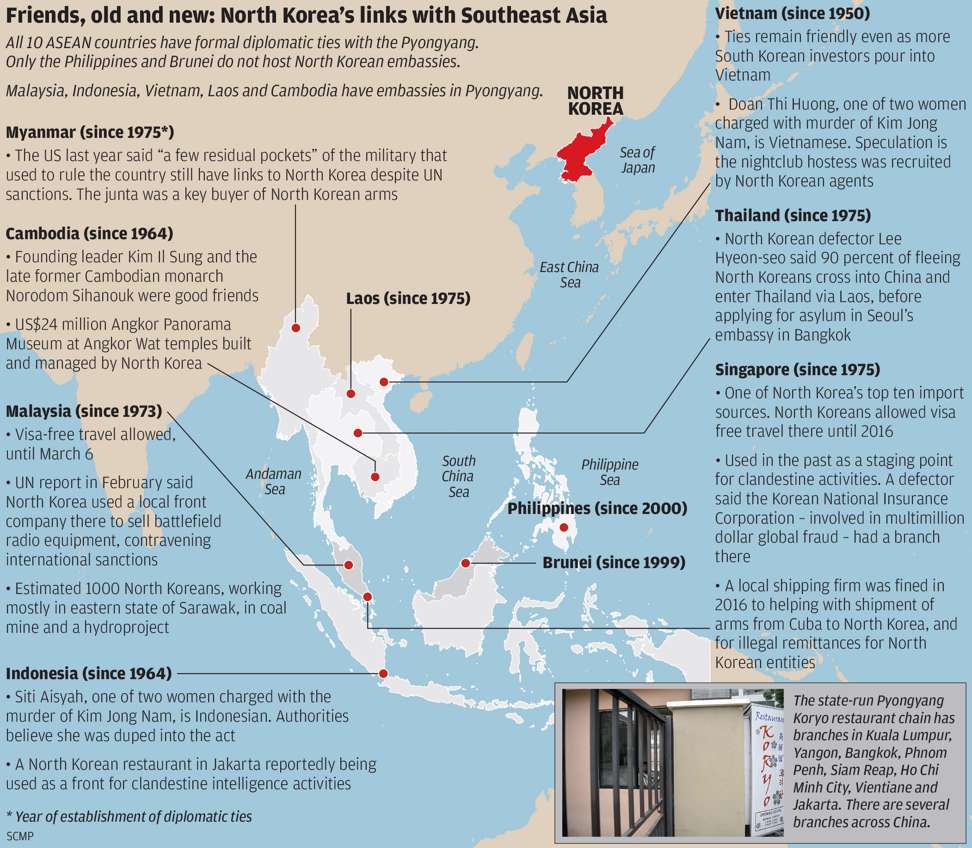

And despite the unsettling circumstances of late, experts say the hermit nation’s bilateral ties with the 10 member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) are unlikely to be adversely affected.

Pyongyang is suspected of being involved in the daylight murder last month of leader Kim Jong-un’s estranged half-brother in Malaysia. Unhappy with official investigations into the episode, Pyongyang shocked Malaysia on Tuesday by blocking Malaysian nationals from leaving its borders.

And with nine citizens virtually being held hostage as a result of the travel ban, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak insisted ties remained “friendly” even as he retaliated with a similar ban on departures by North Korean embassy staff.

“Malaysia always ensures good relations with all countries. However this does not mean any one of them can abuse our good treatment,” the Malaysian leader said in a blog post on Friday.

The conciliatory tone paled in contrast to the US response this week to fresh missile tests by Pyongyang – the “pariah” label was dished out yet again.

Malaysia’s cautious tone, however, belies the fact that Southeast Asian countries are waking up to the reality that their decades-old bond with North Korea, forged during the time of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, may count for little when dealing with the unpredictable third-generation leader Kim Jong-un.

His half-brother Kim Jong-nam, 45, was killed on February 13 after two women – an Indonesian and a Vietnamese – wiped a nerve agent classified as a weapon of mass destruction on his face at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport. He was preparing to board a flight to Macau, where he lived in exile under China’s protection. The elder Kim had previously voiced criticism over North Korea’s dynastic rule, but said he had no interest in politics.

Insecure and paranoid

The murder “is an obvious sign of Kim Jong-un’s significant insecurity…and the fact that he was extremely paranoid about a family member who was not innately hostile,” said David Asher, a former US State Department official who dealt with North Korea.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a long-time Asean observer, said the “assassination” would see Asean close ranks “to stamp out North Korea’s underground activities in the region to avoid future incidents”.

The region ranks behind only China in economic importance for North Korea, whose economy has remained anaemic for years partly because of crippling sanctions imposed on it for its nuclear weapons programme.

The Stalinist state of 24 million people had a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US$1,013 in 2015, according to the Hyundai Research Institute. That compared with US$1,292 in Myanmar and US$1,799 in Laos – two of Asean’s poorest countries.

Japan, US conduct navy drill in East China Sea as ‘warning’ to North Korea

Ong Keng Yong, a Singaporean ambassador-at-large, said Pyongyang’s travel ban was “disturbing”.

“It is important for [North Korea] to understand that a very serious incident has taken place on Malaysian soil and the Malaysian government is obliged to investigate it in accordance with its laws and regulations,” said Ong, a former Asean secretary general.

Critics of Asean’s close ties with North Korea say the episode in Malaysia is a compelling reason for the region to take a harder stance toward Pyongyang. The relaxed diplomatic policy is seen as the main cause for Pyongyang exploiting cities like Kuala Lumpur and Singapore to conduct clandestine activities, the experts say. Singapore ended years of visa-free travel for North Koreans last year, and Malaysia followed suit on Monday, in response to Kim’s murder.

The United Nations in February said North Korean intelligence agents used front companies in Malaysia to sell battlefield radio equipment in breach of international sanctions.

And last year, a Singapore court slapped a US$126,000 fine on a local shipping firm for facilitating a shipment of arms to North Korea from Cuba – another violation of UN sanctions.

“Asean countries do not have to do anything extraordinary here beyond fully implementing UN sanctions which are already stringent,” said Shahriman Lockman, a senior analyst with the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Kuala Lumpur.

The inordinate number of North Korean diplomats accredited in Southeast Asian countries is also seen as a problem.

North Korean Ambassador to Malaysia, Kang Chol, is surrounded by reporters upon his arrival at Kuala Lumpur’s international airport. Photo: Kyodo

Police investigations into Kim’s killing uncovered a web of North Korean operatives who are suspected to have aided in its planning and execution. One is a diplomat. Three suspects remain holed up in the North Korean embassy in Kuala Lumpur, while four others left the country after the killing.

The current diplomatic standoff arose because Pyongyang rejected the need for an autopsy and a relative to identify the remains. Malaysia on Friday formally identified the dead man as Kim Jong-nam, but did not say how it came to that conclusion. North Korea has demurred at identifying him as the half-brother of the current leader, insisting only that he was a citizen holding a diplomatic passport.

Embassy officials, who insisted Kim died of a heart attack, were prevented from collecting his remains soon after his death. Police said there was an attempted break-in at the morgue where the body was kept.

Near miss: North Korean missile ‘fell just 200km from Japanese coast, closer than ever before’

Limiting the accreditation of North Korean diplomats will go some way to curbing the regime’s shady activities that are “geared towards sanctions-busting rather than cultivating diplomatic ties in any normal sense of the term”, Shahriman said.

Disparate national interests

Communist-ruled Vietnam was the first to establish diplomatic relations with its kindred nation in 1950. The Philippines, a key US ally, established ties in 2000, the same year Pyongyang began participating in annual talks with Asean. Ties with Cambodia, another close ally, were established in 1964. The relationship was bolstered by the strong personal friendship between North Korea’s founding leader Kim Il-sung, the grandfather of the current leader, and Norodom Sihanouk, the former Cambodian monarch.

Norodom Sihanouk, former King of Cambodia, left, is welcomed to Pyongyang by North Korean President Kim Il-sung in 1975. Photo: AFP

Norodom Sihanouk, former King of Cambodia, left, is welcomed to Pyongyang by North Korean President Kim Il-sung in 1975. Photo: AFP

Members of Malaysian youth NGO, Solidariti Anak Muda Malaysia, call for peace and diplomatic cooperation between Malaysia and North Korea outside the gates of the North Korean embassy in Kuala Lumpur. Photo: AFP

The region’s more developed countries, such as Singapore, maintain close links in order to have first-mover’s advantage in the event that reunification with the South happens, said Song Jiyoung, a South Korean researcher at Australia’s Lowy Institute for International Policy.

“They have been teaching North Korea Singapore-style capitalism, finance and banking.

“North Korea is a blank market with lots of possibilities. No one wants to trade with them. Why not go there and seize the market first?”

With members having such self-serving national interests, “Asean is unlikely to have a joint response that goes deeper than rhetoric,” said Andrea Berger, a North Korea expert at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in California. Asean insiders are not as pessimistic, however.

Since 2000, Pyongyang has been a participant in the annual Asean Regional Forum (ARF), a meeting that brings together members and 17 friendly countries including the US, Russia, India, China and Pakistan.

“It may appear that little has been achieved through such engagement, but small steps are better than no steps at all,” said Singapore’s Ong, who helmed Asean between 2003 and 2007. “Asean has always believed that dialogue is important.”

For Asher, the former US diplomat, such talks – involving China or Asean – do little to curb North Korea’s belligerence. “Preserving the status quo is nonsensical…North Korea is a nuclear armed global pariah state threatening the security of the Middle East as much as the security of Northeast Asia,” he said.

- Previous 2017, the year Chairman Xi Jinping will come into his own

- Next Prime Minister Narendra Modi Leads Party to Big Win in Indian State Election