Kyrgyzstan’s Law – No More 45% to be Owned its Debt by One Country – to Manage Chinese Debt

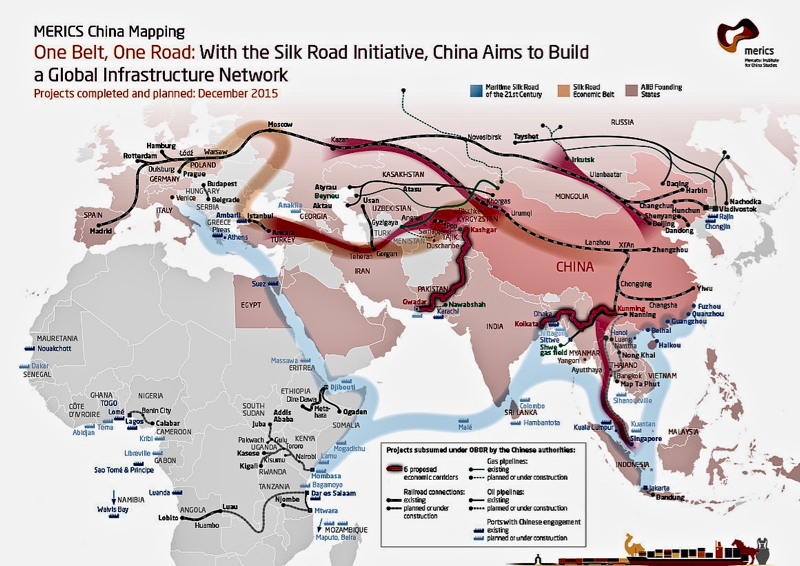

In recent years, China’s economic engagement across Eurasia has become increasingly diverse and complex. What began with large-scale infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative has expanded into a wide range of sectors, including critical minerals, energy, pharmaceuticals, and textiles. Alongside these investments, China has also deepened its soft power presence through Luban Workshops, educational exchanges, and media cooperation with regional countries.

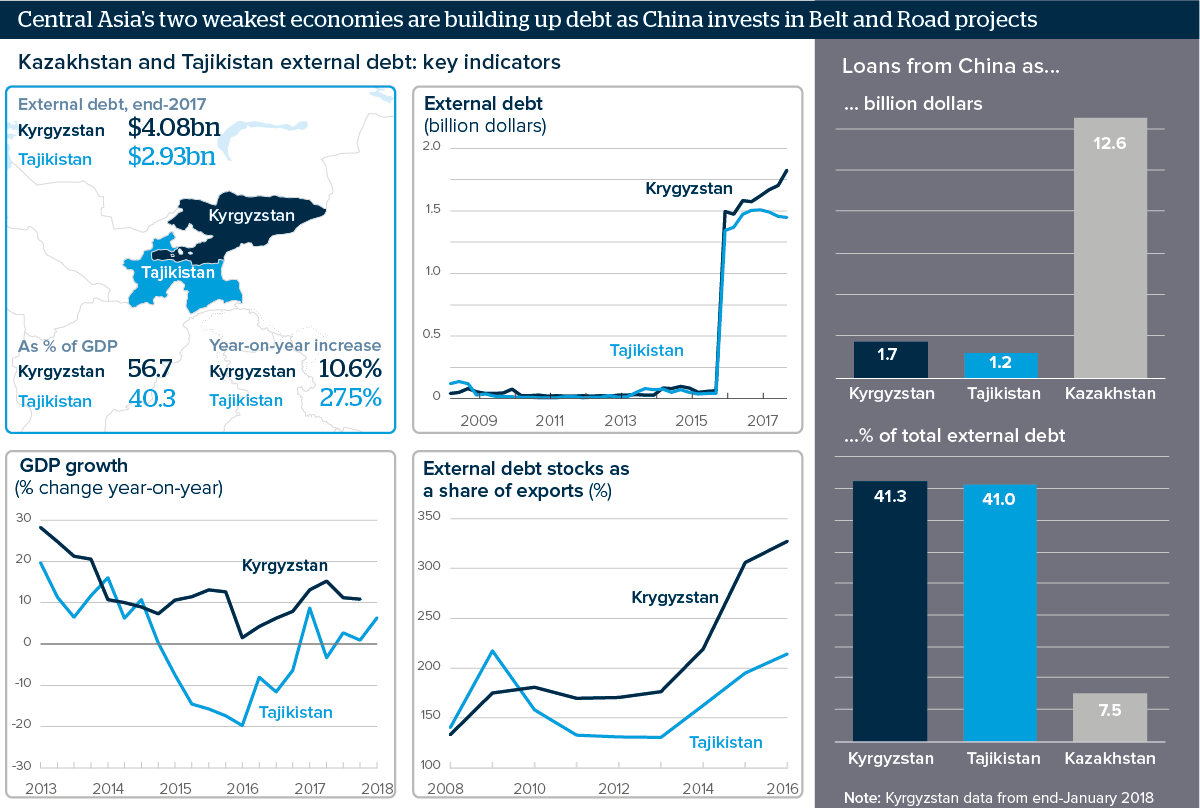

While this growing influence strengthens China’s position as a major development partner, it has also raised public concern about debt dependency. Kyrgyzstan illustrates this issue more clearly than most. In 2022, more than 40% of the country’s official external debt was owed to China. This heavy reliance has sparked debate over whether the relationship creates long-term vulnerabilities that could limit economic independence and policy flexibility.

The scale of the debt has generated several layers of concern within Kyrgyz society. Many worry that national resources are being redirected from essential public needs toward debt repayment. Others fear that financial obligations could eventually lead to asset-for-debt arrangements or serve as a tool of political influence. Kyrgyz governments have therefore explored various ways to ease their debt burden, but with limited success.

Direct Negotiations with China and Innovative Approaches

The first approach has been to negotiate directly with China for relief. However, these talks have mostly produced temporary payment deferrals rather than genuine debt reduction. In November 2020, China Eximbank agreed to postpone $35 million in loan repayments until the period between 2022 and 2024. The agreement remained purely commercial, requiring a 2% fee on the deferred amount and likely continued interest payments.

This arrangement differs from the more concessional restructuring models often offered by multilateral lenders or Paris Club members, which are designed to restore debt sustainability and support economic reform. Chinese state lenders such as the Eximbank tend to approach debt through a commercial logic, emphasizing the protection of contracts and the profitability of Belt and Road projects. As a result, debt forgiveness is considered an unattractive option from the perspective of Chinese financial institutions.

Kyrgyzstan has also experimented with more innovative ideas. The government proposed that creditors forgive part of its debt in exchange for investments in environmental and climate-related projects. These initiatives, often described as debt-for-nature swaps, would redirect funds from debt service toward renewable energy, reforestation, or carbon reduction programs. Although several European partners expressed interest, China declined to participate in 2024.

China’s reluctance reveals an important feature of its lending philosophy. Despite its growing global presence, Chinese state banks continue to prioritize financial security and measurable returns over experimental or non-monetary arrangements. Even when Beijing publicly supports global climate cooperation, its institutions remain cautious about initiatives that fall outside traditional commercial frameworks.

Kyrgyzstan’s New Debt Management Strategies

Kyrgyzstan’s approach to managing its external debt is undergoing a gradual but meaningful transformation. The government has introduced new policies and sought diversified financial partnerships in an effort to strengthen fiscal stability and reduce dependency on any single creditor.

On e of the most significant steps has been the adoption of a legislative debt ceiling that prevents the government from owing more than 45% of its total external debt to any one actor. This measure responds to public concerns about the country’s exposure to Chinese lending, while also reinforcing a sense of fiscal responsibility. The debt ceiling serves a dual purpose by helping officials justify the pursuit of alternative financing and by creating an institutional safeguard against excessive concentration of debt.

e of the most significant steps has been the adoption of a legislative debt ceiling that prevents the government from owing more than 45% of its total external debt to any one actor. This measure responds to public concerns about the country’s exposure to Chinese lending, while also reinforcing a sense of fiscal responsibility. The debt ceiling serves a dual purpose by helping officials justify the pursuit of alternative financing and by creating an institutional safeguard against excessive concentration of debt.

In addition to legislative measures, Kyrgyzstan has begun to explore new instruments to access international capital markets. The government announced plans to raise $1.7 billion through the issuance of ten-year sovereign bonds in Hong Kong. Entry into global bond markets can provide Bishkek with greater financial independence, offering new opportunities to attract investment and diversify sources of capital. Over time, this approach may help establish a more balanced debt structure that is less reliant on bilateral lenders.

Another key component of this evolving strategy is Kyrgyzstan’s growing engagement with multilateral banks and international financial institutions. The country’s borrowing from the World Bank now stands at around $815 million, and its loans from the Asian Development Bank amount to approximately $793 million.

The Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, to which Kyrgyzstan owes about $258 million, has already surpassed the International Monetary Fund, whose loans total $238 million. This shift reflects a deliberate effort to widen the country’s financial partnerships and strengthen its economic resilience.

As a result of these adjustments, the share of external debt owed to China has declined from around 40% to 36%. This change demonstrates that Kyrgyzstan’s diversification strategy is beginning to take effect.

Diversification Goals and Strategic Shifts

Kyrgyzstan’s diversification policy serves several interconnected goals. The first objective is to gradually reduce long-term dependence on Chinese financing while easing public concerns about debt exposure. By doing so, Bishkek is seeking to create the conditions for a more balanced and mutually beneficial partnership with Beijing.

The second goal reflects a qualitative shift in development priorities. Instead of focusing primarily on large infrastructure projects, the government is aiming to channel future financing toward long-term structural needs such as community development, climate resilience, and local governance capacity. The third and perhaps most strategic aim is to enhance Kyrgyzstan’s overall financial credibility, which would help the country mobilize additional resources and attract new investment in the years ahead.

Although the diversification strategy is designed to reduce dependency on Chinese loans, it does not signal an intention to end cooperation with Beijing. On the contrary, the Kyrgyz government continues to view China as an essential economic partner and is looking to shift the relationship from one dominated by debt toward one centered on productive investment and trade.

The success of this approach will depend on Bishkek’s ability to maintain constructive engagement with China while expanding partnerships with other regional and global financial actors. Achieving this balance will be critical for ensuring both fiscal sustainability and long-term development stability.

- Previous IRGC seizes Azerbaijan-linked oil tanker in Strait of Hormuz

- Next Turkiye blocks US delivery of attack choppers to India, helps its Pakistani ally