Chinese scientists guilty of ‘researching while Asian’ in Trump’s America

- Leading cancer researcher Wu Xifeng was hounded from her job at a Texas institution thanks to a hostile political climate in the United States

- Such attitudes are not only stymying life-saving work but also casting cold-war-style suspicion on Chinese-American and Chinese academics

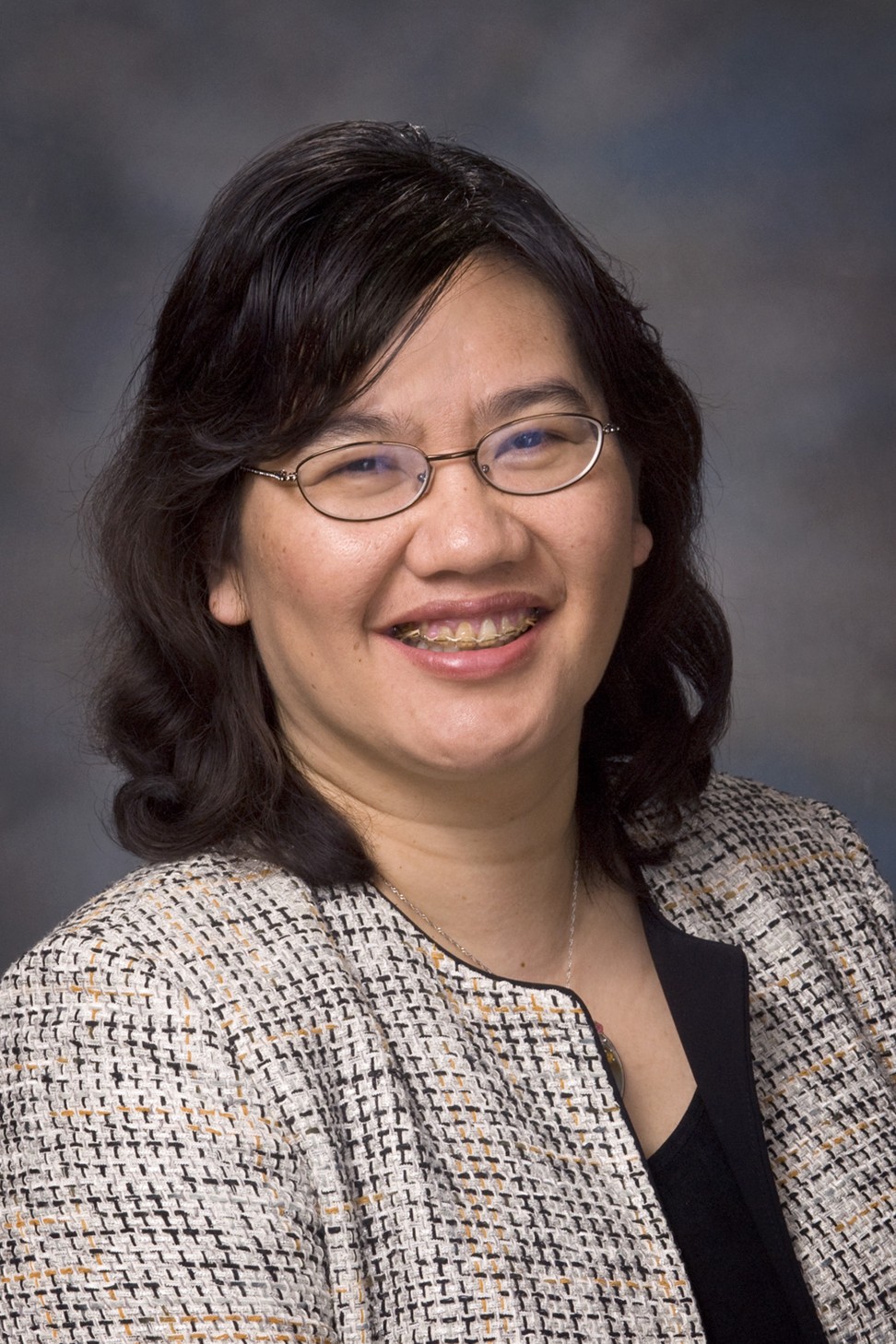

The dossier on cancer researcher Wu Xifeng was thick with intrigue, if hardly the stuff of a spy thriller. It contained findings that she’d improperly shared confidential information and accepted a half-dozen advisory roles at medical institutions in China. She might have weathered those allegations, but for a larger aspersion that was far more problematic: she was branded an oncological double agent.

In recent decades, cancer research has become increasingly globalised, with scientists around the world pooling data and ideas to jointly study a disease that kills almost 10 million people a year. International collaborations are an intrinsic part of the United States National Cancer Institute’s Moonshot programme, the government’s US$1 billion blitz to double the pace of treatment discoveries by 2022. One of the programme’s tag lines: “Cancer knows no borders.”

Except, it turns out, the borders around China. In January, Wu, an award-winning epidemiologist and naturalised American citizen, quietly stepped down as director of the Center for Translational and Public Health Genomics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center after a three-month investigation into her professional ties in China. Her resignation, and the departures in recent months of three other top Chinese-American scientists from Houston-based MD Anderson, stem from a Trump administration drive to counter Chinese influence at US research institutions. The aim is to curb China’s well-documented and costly theft of US innovation and know-how. The collateral effect, however, is to stymie basic science, the foundational research that underlies new medical treatments. Everything is commodified in the economic cold war with China, including the struggle to find a cure for cancer.

The NIH, the world’s biggest public funder of basic biomedical research, wields immense power over the nation’s health-research community. It allocates about US$26 billion a year in federal grants; roughly US$6 billion of that goes to cancer research. At a June 5 hearing, NIH officials told the US Senate Committee on Finance that the agency has contacted 61 research institutions about suspected diversion of proprietary information by grant recipients and referred 16 cases, mainly involving undisclosed ties to foreign governments, for possible legal action. Ways of working that have long been encouraged by the NIH and many research institutions, particularly MD Anderson, are now quasi-criminalised, with FBI agents reading private emails, stopping Chinese scientists at airports, and visiting people’s homes to ask about their loyalty.

Wu hasn’t been charged with stealing ideas, but in effect she stood accused of secretly aiding and abetting cancer research in China, an un-American activity in today’s political climate. She’d spent 27 of her 56 years at MD Anderson. A month after resigning, she left her husband and two children in the US and took a job as dean of a school of public health in Shanghai.

This is the first detailed account of what happened to Wu. She declined to be interviewed for this article, citing a pending complaint she’s filed with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Her story is based on interviews and documents provided by 14 American colleagues and friends and records obtained through the Texas Public Information Act.

Wu graduated from medical school in Shanghai and earned her PhD in 1994 from the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston. She joined MD Anderson while in graduate school and gained renown for creating several so-called study cohorts with data amassed from hundreds of thousands of patients in Asia and the US. The cohorts, which combine patient histories with personal biomarkers such as DNA characteristics and treatment descriptions, outcomes and even lifestyle habits, are a gold mine for researchers. For example, Wu and her team showed that Mexican-Americans who sleep less than six hours a night had a higher risk of cancer than Mexican-Americans who get more sleep, and that eating charred meat such as barbecue raised the risk of kidney cancer. In 2011, Wu leapfrogged older colleagues and was named epidemiology chair, making her the top-ranked epidemiologist at the nation’s top-ranked cancer centre.

Along the way, Wu developed close ties with researchers and cancer centres in China. She was encouraged to do so by MD Anderson. The centre’s president in the early 2000s, John Mendelsohn, launched an initiative to promote international collaborations. In China, MD Anderson forged “sister” relationships with five major cancer centres, cooperating on screening programmes, clinical trials, and basic research studies. Dozens of ethnic Chinese faculty members at MD Anderson participated, eager to visit family and friends and contribute their expertise to addressing China’s enormous burden of about 4.3 million new cancer cases a year. In 2015, China awarded MD Anderson its top honour for international scientific cooperation, in a ceremony attended by President Xi Jinping.

Wu was a model collaborator. She attended Chinese medical conferences, hosted visiting Chinese professors in Houston, and published 87 research papers with co-authors from 26 Chinese institutions. In all, she has co-authored some 540 papers that have been cited about 23,000 times in scientific literature. (Her papers are all easily retrievable with a few clicks on MD Anderson’s website.)

Innocent yet meaningful scientific collaborations have been portrayed as somehow corrupt and detrimental to American interests. Nothing could be further from the truth

“MD Anderson was very much an open door. The mission was ‘End cancer in Texas, America, and the world’,” says Oliver Bogler, the cancer centre’s senior vice-president for academic affairs from 2011 to 2018 and now chief operating officer of the ECHO Institute at the University of New Mexico.

The globalisation of science, in particular basic science, has been sweeping. “Faculty don’t see international borders any more,” says Adam Kuspa, dean of research at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “If someone in another country has a piece of the puzzle, they want to work with them.” Relationships often begin at academic conferences, gel during invited visits for symposiums or lectureships and culminate in the melding of research into scientific papers. Since 2010 the NIH has offered about US$5 million a year in grants for US-China collaborations, with 20 per cent going to cancer research, and a counterpart in China has pitched in US$3 million a year. The joint projects have produced a number of high-impact papers on cancer, according to an internal NIH review.

For Kirk Smith, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley who studies the health effects of air pollution, the benefits of collaboration have been surprising. He never imagined, back in the 1980s, when he started researching Chinese air pollution with Chinese scientists, that his colleagues would become policymakers at home. In the past six years, Smith’s partners have pushed through standards that have seen air pollution fall by up to 42 per cent in China’s most populous areas. The results have borne fruit in the US, too. Twenty years ago scientists forecast air pollution from China, blowing across the Pacific, would cause California to exceed its clean-air standards by 2025. Now that won’t happen, says Smith, who was granted an honorary professorship at Tsinghua University this spring.

Wu’s work, like much of the academic research now in danger of being stifled, isn’t about developing patentable drugs. The mission is to reduce risk and save lives by discovering the causes of cancer. Prevention isn’t a product. It isn’t sellable. Or stealable.

Suspicion of Chinese scientists at MD Anderson began to take root in 2014. The year before, a Chinese researcher at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee had been arrested on federal charges of economic espionage; prosecutors said he stole three vials of a cancer drug in early-stage lab testing. (He pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of accessing a computer without authorisation and was sentenced to time served, 4½ months.) At the time, MD Anderson was pushing to commercialise basic research into cancer drugs; today the centre has alliances and partnerships with almost three dozen pharmaceutical makers and other private companies. Security was enhanced. Foreign guests were kept on a short leash.

The chain of events that ultimately led to Wu’s departure began in the summer of 2017, when the FBI notified the cancer centre it was investigating “the possible theft of MD Anderson research and proprietary information”. (MD Anderson declined to speak about the FBI investigation except to say it did not report theft of intellectual property to the bureau.) A federal grand jury followed up with a subpoena for five years of emails from some MD Anderson employees. A few months later, the centre gutted its international research programme and put what was left of its collaborative-project arm under a business department. Bogler and former colleagues within the centre say the focus then shifted away from research collaborations and toward business opportunities. MD Anderson spokeswoman Brette Peyton said in an email that the centre’s global programmes haven’t changed.

In November 2017, the FBI asked for more information. This time, no subpoena followed. Instead, the cancer centre’s president, Peter Pisters – then on the job for barely a month – signed a voluntary agreement allowing the FBI to search the network accounts of what a separate document indicated were 23 employees “for any purpose […] at any time, for any length of time, and at any location”. Did all of the network accounts handed over to the FBI belong to Chinese or Chinese-American scientists? MD Anderson refuses to say.

In Wray’s telling, China’s challenge to the US today is unlike any that nation has faced. Whereas the cold war was fought by armies and governments, the contest is being waged, on China’s side, by the “whole of society”, the FBI director said, and the US needs a whole-of-society response. But what does that look like in a society with more than 5 million citizens of Chinese descent?

In the same way racial profiling of African-Americans as criminals may create the crime of ‘driving while black’, profiling of Asian-Americans as spies may be creating a new crime: ‘researching while Asian’

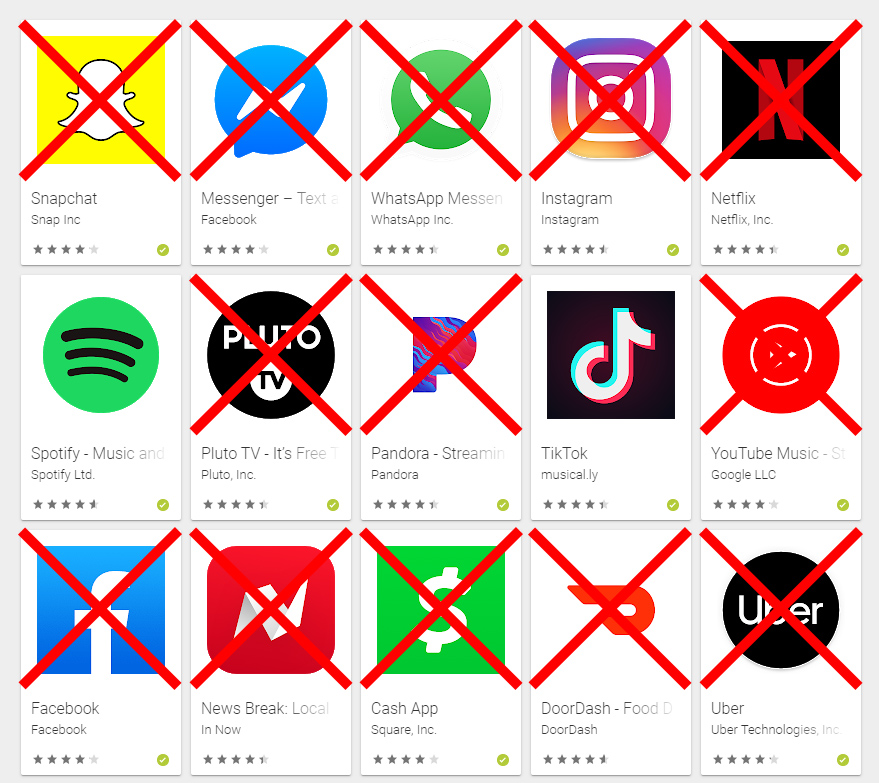

The FBI is telling companies, universities, hospitals – anyone with intellectual property at stake – to take precautions when dealing with Chinese business partners and employees who might be what Wray calls “non-traditional” information collectors. US Department of Justice officials are doing roadshows to brief local governments, companies and journalists about China’s perfidy. Visas for Chinese students and researchers are being curtailed, and more Chinese engineers and businesspeople, especially in the tech sector, are being detained at US airports while border agents inspect their digital devices. The FBI is pursuing economic espionage investigations “that almost invariably lead back to China” in almost every one of its 56 field offices, Wray said.

They’ve made some big arrests. Last year, the agency lured an alleged spymaster affiliated with China’s Ministry of State Security to Belgium, where he was arrested and extradited to the US to face espionage charges. The suspected agent, named Yanjun Xu, allegedly disguised himself as an academic and used LinkedIn to entice a Chinese-American engineer at GE Aviation in Cincinnati to come to China to give a presentation on composite materials for the aerospace industry. The engineer brought along some of his employer’s confidential documents. Xu pleaded not guilty in October and remains in custody in Ohio awaiting trial. The GE Aviation employee wasn’t charged.

Cardozo Law Review

“In the same way racial profiling of African-Americans as criminals may create the crime of ‘driving while black’,” wrote Kim, who practices law at the Houston office of Greenberg Traurig, “profiling of Asian-Americans as spies […] may be creating a new crime: ‘researching while Asian’.”

In 2015, FBI agents stormed the Philadelphia home of Xiaoxing Xi, a Temple University physicist, and arrested him at gunpoint in front of his wife and two daughters for allegedly sharing superconductor technology with China. The charges were dropped five months later, after Xi’s lawyers proved the system in question was old and publicly available. But Xi says his life will never be the same. He lost most of his graduate students and research funding and remains preoccupied with fears that the government is still spying on him. “Seeing how such a trivial thing could be twisted into felony charges has had a dramatic psychological impact,” he says. “I was doing academic collaboration that the government, the university, and all the funding agencies encouraged us to do.”

Last spring, FBI agents in Houston, armed with a batch of emails from the 23 accounts, knocked on the doors of at least four Chinese-Americans who worked at MD Anderson, asking whether they or others had professional links to China. The agents were particularly interested in scientists connected to China’s Thousand Talents Plan, a government initiative to lure back top scholars from overseas with well-paid jobs in China. A report last year by the US National Intelligence Council said the recruitment programme’s underlying purpose is “to facilitate the legal and illicit transfer of US technology, intellectual property and know-how” to China.

“I told them I wasn’t going to snitch,” says one person, who was surprised to find two agents at his back door one afternoon. They told him not to discuss the encounter, says the person, who asked not to be named, and inquired about joint research projects in China. He tried to explain that there are no secrets in basic science, because everything gets published. Over their two-hour talk, he says, the agents were less focused on national security issues – say, espionage or trade-secret theft – than on the more soul-searching subject of loyalty. They wanted to know, in effect, are you now or have you ever been more committed to curing cancer in China than in the US? An FBI spokesman wouldn’t comment, but said that the bureau can’t initiate investigations “based solely on an individual’s race, ethnicity, national origin or religion”.

That June, MD Anderson gave the FBI another consent letter, this time permitting it to share any “relevant information” from the cancer centre’s employee accounts with the NIH and other federal agencies. That signalled a new focus for the ostensible national security investigation: compliance with federal grant requirements. It was here that Wu became a target.

In five memos addressed last autumn to Pisters, MD Anderson’s president, a top NIH official cited dozens of employee emails in claiming that Wu and four other scientists at the cancer centre violated confidentiality requirements in grant reviews and failed to disclose paid work in China. “Because NIH awards generally are made to the institution and not the [researcher], we remind you of the gravity of these concerns,” wrote Michael Lauer, NIH’s deputy director for outside research. He gave Pisters 30 days to respond.

The investigations of the MD Anderson employees were handled by the centre’s compliance chief, Max Weber, and his boss, general counsel Steven Haydon. On the advice of her lawyer, Wu, who had an often-combative relationship with the administration, declined to be interviewed by Weber but submitted written responses to questions. In them she acknowledged lapses, but maintained they weren’t duplicitous. She admitted sharing NIH grant proposals with US colleagues – not to leak scientific secrets, she said, but to get help with her workload. Wu told Weber she used office administrators and more junior researchers to perform such tasks as downloading and printing grant proposals and typing and editing review drafts. Weber concluded that Wu’s use of others to help with grant reviews violated MD Anderson’s ethics policies.

If that’s true, the position is at odds with common practice in academia. “If you searched through MD Anderson or any large research institution, you’d find people with these kinds of compliance issues everywhere,” says Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken School of Public Health at George Washington University. Assisting senior scientists with confidential grant reviews, a rite of passage for many younger researchers, is considered “part of the mentoring process” by older faculty members, Goldman says. “Is it wrong? Probably. Is it a capital offence? Hardly.”

Wu acknowledged accepting various honorary titles and positions in China, such as advisory professor at Fudan University, her alma mater – but she wasn’t paid, she said. She produced emails showing she twice withdrew from Thousand Talents consideration, because the positions entailed too much travel. In his report, Weber wrote that Wu failed to disclose compensated work at Chinese cancer centres. He offered no proof that she’d been paid, but included potential salary amounts for certain positions in his report, conditioned on “actual work performed”, he wrote. He offered no evidence that she did any work.

Weber based most of his conclusions on “adverse inferences” he drew from Wu’s insistence on responding to his questions in writing. For example, he cited a 2017 article on the website of Shanghai’s Ruijin Hospital that said Wu had been honoured at a ceremony after signing a contract to become a visiting professor. “Given Wu’s failure to appear at her interview, I infer that this fact is true,” Weber wrote.

Yet a week after that article appeared, Wu emailed Ruijin Hospital’s president to say she couldn’t accept the appointment before clearing it with MD Anderson’s conflict-of-interest committee. Twelve days later, she emailed him a draft consulting contract that specified the pact was subject to all rules and regulations of MD Anderson, including those related to intellectual property. “If you agree, I will submit it to our institution for review,” Wu wrote. The Chinese hospital did agree, and she submitted the draft contract to MD Anderson. She never heard back from the conflict-of-interest panel before resigning.

Weber didn’t mention either email in his report. Wu was placed on unpaid leave pending disciplinary action, including possible termination. She quit on January 15. Wu didn’t exercise her right to challenge Weber’s findings at a faculty hearing, Peyton said. “Subsequent protestations of innocence are unfortunate.” Weber didn’t respond to a request for an interview.

The greatest fear is that history may repeat itself in this political climate, and Chinese-Americans may be rounded up like Japanese-Americans during World War II

To friends and many colleagues, Wu’s case represents overkill. There was no evidence, and no accusation, that she’d given China any proprietary information, whatever that term might mean in cancer epidemiology. She should have been given the chance to correct her disclosures without punishment, her supporters say. “Innocent yet meaningful scientific collaborations have been portrayed as somehow corrupt and detrimental to American interests. Nothing could be further from the truth,” says Randy Legerski, a retired vice-chair of MD Anderson’s genetics department and former chair of its faculty senate. Adds Goldman of George Washington: “The only thing we’ve lost to China is our investment in Xifeng Wu.”

In an interview, Pisters wouldn’t comment on any of the five investigations of Chinese researchers, but said MD Anderson had to act to protect its NIH funding, which reached US$148 million last year. The cancer centre has a “social responsibility” to taxpayers and its donors to protect its intellectual property from any country trying “to take advantage of everything that is aspirational and outstanding in America”, he said.

On a Saturday this March, about 150 ethnic Chinese scientists and engineers packed a University of Chicago conference room for a panel discussion titled, “The New Reality Facing Chinese Americans”. Speakers from the FBI and US attorney’s office assured everyone that multiple layers of government review ensure agents follow the law, not prejudices.

Panellist Brian Sun, partner-in-charge of the Los Angeles office of Jones Day, shot back that prosecutors’ inflammatory rhetoric in Chinese spying cases has repeatedly stoked public fear, only to have prosecutions collapse. The audience gasped when he described the failed espionage indictment of National Weather Service hydrologist Sherry Chen, who was charged in 2014 with accessing data on US dams to give China. At one point prosecutors said the information could possibly be used during wartime to cause mass murder by blowing up the embankments. It turned out that federal investigators knew Chen had legitimate work reasons to retrieve the dam information, and she never passed any of it to China.

Nancy Chen, a retired federal employee, closed the meeting by raising the unspoken dread in a room full of scholars familiar with the long history of US laws and executive orders aimed at Asian immigrants. “The greatest fear is that history may repeat itself in this political climate, and Chinese-Americans may be rounded up like Japanese-Americans during World War II,” she said. “The fear and worry is real.”

The FBI agent thanked Chen for her comments and said the “atmospheric” information is always good to know.

An automatic suspicion of people based on their national origin can lead to terrible consequences

So far, MD Anderson and Emory University, which fired two Chinese-American professors in May, are the only US research institutions known to have parted company with multiple scientists over alleged breaches of NIH disclosure rules. The University of Wisconsin at Madison rebuffed an FBI request for computer files of a Chinese-American engineering professor without a subpoena, according to a person familiar with the matter. Yale, Stanford and Berkeley, among other institutions, have published letters of support for Chinese faculty members and research collaborations. “An automatic suspicion of people based on their national origin can lead to terrible consequences,” wrote Berkeley chancellor Carol Christ in February.

Baylor College of Medicine, located next door to MD Anderson at Houston’s Texas Medical Centre, received NIH inquiries about four faculty members. It didn’t punish anyone, but used the opportunity to correct past disclosure lapses and educate faculty members about more rigorous enforcement going forward, says Kuspa, the school’s research dean. Local FBI activity has rattled enough nerves already, he says. “Chinese scientists have come to me shaking.”

After attending several FBI briefings on the China threat, Kuspa wonders if the bureau understands how long and painstaking cancer research is. It can take two decades from discovery of a promising molecule to approval of a chemotherapy drug. Even then, progress in cancer treatment is measured in months of life, seldom in years. How much basic cancer research could China really steal?

“I joke with my boss after those FBI meetings, ‘Darn, I guess the Chinese are going to cure cancer. I’ll buy that pill,’” Kuspa says. “Isn’t that what we’re supposed to do – educate the entire world to have a fact-based approach to health?”

Additional reporting by Lydia Mulvany and Selina Wang.

Bloomberg Businessweek

- Previous Is ‘Made in China 2025’ as big a threat as the West thinks it is? Beijing looks east to Taiwan for chips

- Next Trump shakes hands with Saudi crown prince in G20 family photo while others wave