Israeli farmers sweat as land they worked for decades to be given back to Jordan

Jerusalem will soon have to cede control of two parcels of land after Amman refused to extend lease outlined in peace accord; tenants say the government has failed them

Omer Sharvit

Dozens of Israeli farmers are facing an uncertain future after being informed that the land that they have been working for decades will soon be handed back to Jordan.

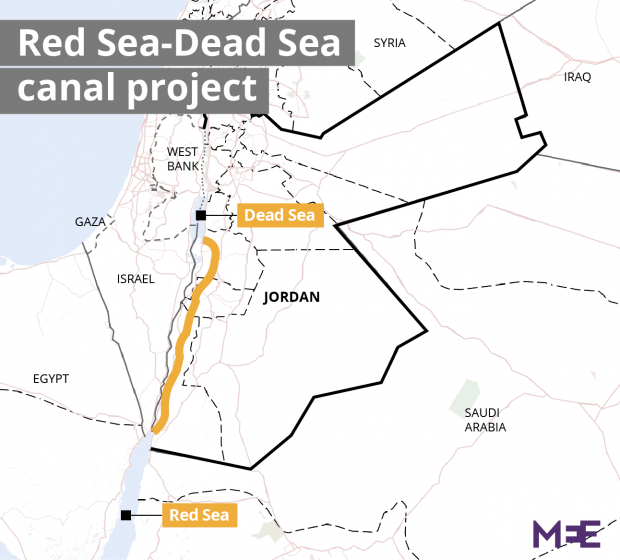

The area in question comprises two parcels of agricultural land: Naharayim, known in Arabic as Baqoura, in the Jordan Valley, and Tzofar, or Ghumar, in the Arava region in southern Israel, which together span 1,000 dunams (247 acres). These enclaves also include the Island of Peace, a park located at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers.

A special clause in the 1994 peace treaty between the countries allowed Israel to retain use of the land for 25 years, with the understanding that the lease will be renewed as a matter of routine. However, in October 2018, amid domestic unrest in Jordan, King Abdullah II announced plans to terminate the lease, and despite lengthy efforts by the Israeli government, negotiations to guarantee continued access to the areas were unsuccessful.

In hindsight, Jordan’s decision not to extend the lease was predictable, he said, adding that for several years, local farmers have only been cultivating low-maintenance crops in Naharayim, so as to overcome what he called the erratic behavior of the Jordanian officers guarding the site.

There were more than a few times when Israeli farmers and their workers were denied access to the land at the random whim of a Jordanian officer, he noted.

“At the time, we just thought the Jordanians were flexing their muscles. We didn’t know that they were going to demand the land’s return. Looking back, I can say that they were laying the groundwork for it,” he said.

Reuveni leveled harsh criticism at Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel and Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz that the negotiations with Jordan over the land had deadlocked and therefore they will be returned to Amman’s control.

“Ashdot Yaakov has invested millions there over the years and no one thinks to talk to us. Agriculture wasn’t exactly a top priority for the last [agriculture] minister,” he said, adding that the issue of compensation for Israeli farmers is being ignored.

“I, personally, have 200 dunams [50 acres] over there and no one is talking to me about compensation,” Reuveni said. “Even if they do, no one takes it seriously. For [government officials], it’s like, ‘What’s the big deal?’”

“All these years we knew that this area has political significance that goes far beyond agriculture, which is why [Israel] had to keep it. Suddenly, [the government] changed direction completely. We thought that now that the Jordanians got more water from Israel the problem would be solved, but the state didn’t fight for this land,” he said.

Under the treaty, Israel agreed to supply Jordan, which is suffering from a severe water crisis, with 45 million cubic meters of water every year. In recent years, this amount was increased to 55 million cubic meters of water. In 2018, facing the growing challenge of caring for refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria, Amman has again asked for more to 100 million cubic meters.

According to Reuveni, in a move kept largely quiet, the government agreed — something he said could only have been achieved at Steinitz’s request. “[But] what does Steinitz care? He’s never even been here,” Reuveni said.

‘The intention was always to extend the lease’

Orna Shimoni, a resident of neighboring Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov Meuhad, said the land in question symbolizes the Zionist roots of Ashdot Yaakov. In the 1930s, local residents labored to construct engineer Pinhas Rutenberg’s innovative hydroelectric power station, the ruins of which can still be seen in Naharayim today.

Shimoni has visited the Israeli side of Naharayim daily for the past 23 years to tend to the flower garden memorializing seven teenage schoolgirls murdered there in 1997, while on a school trip to the Island of Peace.

In the wake of the attack, which left six other students seriously wounded, Jordan’s King Hussein personally visited the girls’ families to extend his condolences and apologize on behalf of his country. But despite this unique gesture, the shooting, which has come to be known as the “Island of Peace massacre,” has also come to symbolize the cold peace between the two countries.

Like Reuveni, Shimoni, too, bristled at the thought of ceding the land.

“These are lands [then-prime minister Yitzhak] Rabin gave King Hussein as a gesture, in an attempt to forge warmer peace. Hussein asked for peace and water – nothing else. Rabin thought it would be right to offer the land in Naharayim and Tzofar to make the peace deal easier for the Jordanian people and the Arab world to digest. But it was always understood that in 25 years, the lease will be renewed,” she asserted.

Retired Supreme Court Justice Elyakim Rubinstein, who served as chief negotiator vis-à-vis the Jordanians and helped hammer out the language of the treaty, agrees that the spirit of the agreement intended for the lease to be extended after 25 years.

“The intention was to extend the agreement automatically. How do I know? That’s what it says,” he told Zman Yisrael. “True, there is a section that the Jordanians have implemented, whereby they can announce a year in advance that the territory is to be returned, but the intention of both leaders was obviously to extend the lease. It is not often that the term ‘automatically’ is used.”

Low profile, high hopes

Still, the farmers at the two Ashdot Yaakov kibbutzim fare better than their counterparts in Tzofar in southern Israel, who work an area spanning 1,200 dunams (296.5 acres) of high-maintenance crops that require irrigation.

According to Reuveni, “We’re doing better than those in Tzofar because they don’t have other lands — they are private individuals who work the land and have active hothouses. Maybe some of them were offered money so as not to cause trouble, but I can’t really say. In Ashdot the local council is handling it.”

The Central Arava Regional Council is trying to keep a low profile on the matter and, in lieu of a comment, has referred Zman Yisrael to a public relations firm retained to handle any questions from journalists. When contacted, the firm also declined to comment.

Jordan Valley Regional Council Head Idan Greenbaum, for his part, said that “there are talks with the Jordanians and we hope to reach an agreement. The Israeli Foreign Ministry is working with its Jordanian counterpart and the National Security Council is working with Amman, but right now, I don’t think chances of success are high.”

“It would be unfortunate if the land that has been cultivated by the Ashdot kibbutzim for over 70 years is ceded to the Jordanians, and it goes against the spirit of the peace treaty between King Hussein and Yitzhak Rabin. We are connected to this land. In harder times in the past, people gave their lives to continue working this land. So this is hardly something we welcome,” Greenbaum said.

According to Greenbaum, the Jordanian decision may be an attempt to pressure Israel on other issues, such as increasing the annual water allotment.

Israel most probably agreed to the latter in order to appease Jordan over its failure to promote a 2015 deal in which Israel committed to purchasing water for agriculture from a desalination facility that is due to be established in Aqaba, he said.

Israel has also been dragging its feet on a joint project with Jordan for a canal liking Rwe Swa and Dead sea. The agreement on the canal was signed in 2013, with the aim of helping to alleviate Jordan’s severe water shortage while also helping replenish the rapidly shrinking Dead Sea, but it has yet to be implemented.

Greenbaum believes Jordan’s decision against renewing the lease for the border-adjacent lands “is an expression of their frustration over the fact that Israel is stalling on joint projects, like the Red-Dead canal. They bundle it all together and they’re disappointed that Israel isn’t honoring the agreements to which it is party. That’s why they won’t budge on the enclaves in Naharayim and Tzofar.”

The Foreign Ministry declined to respond to Zman Yisrael’s request for comment, referring it to the National Security Council, which is tasked with negotiating the issue with the Hashemite Kingdom.

A diplomatic source confirmed that “diplomatic talks on the issue are indeed taking place and involve the National Security Council and the Foreign Ministry. Naturally, the issue cannot be elaborated upon. Simultaneously, talks are being held between the acting chief of staff at the Prime Minister’s Office and the heads of the local councils.”

Discussion closed?

But Jordanian sources familiar with the issue insist King Abdullah has said the final word on the subject.

Daoud Kuttab, a Jordanian journalist who is a contributing writer for Middle East analysis website Al-Monitor, told Zman Yisrael that an inquiry he made with the Jordanian government on the issue yielded a response saying the land will return to Jordan’s control in early November.

According to Kuttab, any current negotiations focus on the technical issues of ceding the land.

“This issue has great political significance in Jordan,” he explained. “People were pressuring the government and were waiting for October. As far as I know, there was no real attempt to negotiate [a lease extension], and even if an attempt would have been made, the Jordanian government would have said no.”

Former Israeli ambassador to Amman, Oded Eran, also believes that as far as Jordan is concerned, the discussion is closed.

“At this point, the Jordanians have decided not to extend the agreement by which Israel can hold onto both enclaves for [another] 25 years. It’s not about extending a lease because there is no lease to speak of. The lands are under Jordanian sovereignty and were in Israel’s care. Now they have to be returned.”

But does Israel have any leverage it could use to retain its hold on Naharayim and Tzofar? In a few months, the $10 billion deal by which 45 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Israel’s Leviathan offshore gas field will be pumped to Jordan over the next decade is set to come into force, despite scathing criticism by nationalist Jordanian lawmakers.

Eran, for his part, advised against using the deal to push back against the decision on Naharayim and Tzofar.

“The negotiations were held between the Jordanian power company and the American partners in Leviathan [Noble Energy],” Eran said. “Israel also agreed to increase the water supply to Jordan. If Israel goes back on these deals it will be in violation of the [peace] treaty. Jordan isn’t violating the treaty by demanding the lands back, it simply chose not to extend the clause” allowing Israel to hold on to the two enclaves.

This type of rhetoric has never been welcome in Jordan, whose population is mostly Palestinian, but Eran does not believe it had any effect on Amman’s decision regarding the two enclaves.

According to Eran, Jordan still sees maintaining good relations with Israel a key interest, “But Amman’s government still faces considerable internal pressure. So for King Abdullah, opting against extending the lease on Naharayim and Tzofar is a way to appease lawmakers opposing the treaty without actually violating it.”

However this story ends, it is clear it will be a touchstone for future deals with the Palestinians and perhaps, one day, for peace deals with Lebanon and Syria.

Shimoni noted that “every peace deal always includes a land component. King Hussein wanted peace with Israel and he agreed to the Naharayim and Tzofar deal because there was nothing there but tourism and agriculture. Jordan wants tourism [to flourish] but tourists won’t go where farmers can’t go. So it’s not good for Jordan for that land to become desolate.”

There is more to the two enclaves than their agriculture value, she continued: “Both parties feel very strongly about not making any changes to the peace treaty — if we wanted to do that, we could have done so after the girls were murdered.”

“But giving the Island of Peace back will gnaw at the treaty, so you can’t underestimate it and dismiss it as mere agricultural land,” she said. “This is Ashdot’s land — that’s anchored in the peace deal, so under international law, they [Jordan] have no claim to it.”

Shimoni further asserted that potential contention is exactly why the memorial for the slain girls “was not founded on the island itself. The Jordanians would never have agreed to that. Instead, it was founded in a place that was uncontested, a place that anyone can visit freely, day or night.”

According to Reuveni, reducing Israeli presence in the area poses a security risk because if the regime in Jordan becomes destabilized, hostile elements could find it easier to infiltrate the border.

“We all know how things work in the Middle East. All of a sudden, I could wake up and Islamic State or other hostile elements will surround my kibbutz,” said Reuveni. “People who don’t live here don’t understand that — they dismiss it as ridiculous.”

- Previous Joy in Jordan as Amman reclaims enclaves formerly annexed by Israel

- Next Jordan to go ahead with Red Sea-Dead Sea project despite Israel’s withdrawal threat