Kenyan Tea, a Reliable Export, Brews a Market at Home

Domestic sales have jumped since 2010; one firm targets millennial buyers with ‘Attitude’ brand

MOMBASA, Kenya—This nation exports more tea than any other in the world, but for years Kenyans weren’t able to enjoy a cup of premium tea cultivated in their own country. One company is leading a movement to change that.

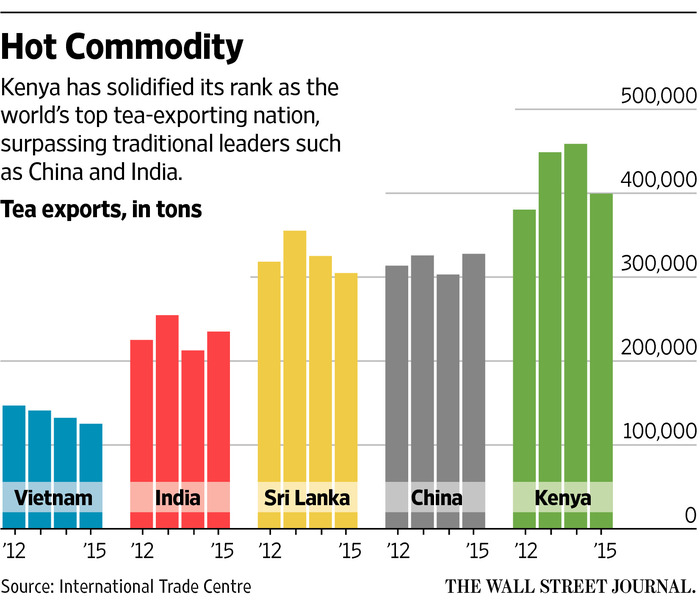

Kenya annually exports roughly 400,000 tons of tea, ahead of other leading producers such as China and India. But high-quality tea was widely viewed as a luxury here, and for decades few Kenyans drank it. About 5% of Kenya’s tea crop stays in the country, much of it dust and residue from higher-quality leaves sold and processed abroad, and many Kenyans use it to make the hot, milky brew known as chai.

In recent years, however, a locally produced premium brand has appeared, shelved in supermarkets next to the 400 shilling ($4) packs of Unilever PLC’s Lipton and Associated British Foods PLC’s Twinings, which are both made with Kenyan tea abroad and re-imported.

Gold Crown Beverages Ltd., a family-held business incorporated in the U.K. but with a base here in Kenya’s biggest port city, is selling premium black and herbal teas, made by Kenyans for Kenyans, at roughly half the price of foreign competitors. The company’s Kenyan sales, $9 million in 2016, have almost tripled since 2012.

Gold Crown has managed to establish a product that doesn’t rely on exporting raw materials and importing processed goods, a feat that has long eluded most African companies. Cocoa producers in Ivory Coast and Ghana have for decades failed to produce a competitive brand of African-made chocolate. Oil producers in Nigeria and Angola have struggled to refine and process their own petroleum products.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has urged Kenya to go further than just exporting tea and add more value to the commodity at home.

“There exists an enormous blue-sky opportunity to roll out higher-quality tea like purple tea too,” said Aly-Khan Satchu, a Kenyan financier and investor, who referred to rare tea grown here that turns the water purple when brewed.

Kenya’s domestic tea sales were $118.6 million in 2015, up from $70 million in 2010, according to Euromonitor, a market-research company.

A cooperative of hundreds of thousands of small-holder Kenyan tea farmers dominates the market through Kenya Tea Packers Ltd. Their brands, cheaper and with far more reach than any competitor in rural areas, are often sold loose and in easily identifiable yellow-and-green packaging.

At the same time, the Kenyan Tea Development Association, a central cooperative for farmers, is working to improve design and packaging of premium black tea to make it appeal to wealthier consumers.

Kenyans have been developing a taste for upmarket hot beverages. While standard black tea sales—the bulk of all tea sales in Kenya—grew by some 40% between 2010 and 2015, the sales of the more expensive teas nearly doubled, Euromonitor found.

Others are now jumping in to compete with Gold Crown. Three small, local tea companies, albeit more modest and cheaper, have opened up in recent months.

When they first opened shop in 2003, Gold Crown Managing Director Fahim Ahmed and his brother planned to be tea traders, procuring leaves for the rest of the world.

Mr. Ahmed says they soon saw an opportunity to also sell tea to Kenyans.

“While we have brilliant tea here, what you found on the shelves was terribly packaged and we thought, well, we’re here so why not do something about it?” Mr. Ahmed said.

The company’s ascent is visible here at the world’s biggest tea auction, where each week a broker with a gavel sells off some $25 million worth of tea. The market’s 100-seat, air-conditioned amphitheater is protected by a heavy door with a fingerprint scanner. Crown Gold is now the second-biggest buyer, behind Unilever.

Beyond black tea, marketed under the Kericho Gold brand, the company sells Kenyans herbal teas, such as mint and camomile, as well as locally grown green tea for blended products.

In October, Gold Crown launched Attitude Tea, a boldly colored brand that is targeted at millennials with blends called “Hangover Tea” and “Love Tea.”

In a supermarket in Nairobi’s upmarket Lavington neighborhood, Mary Mwangi, a 23-year-old accountant, said she gets a sense of pride consuming local products. “I think it’s better tea than anything else we get, and it’s made here,” she said as she tossed a package of Kericho Gold in her basket. “Why should I pay more to buy Kenyan tea made in England?”

Even with its rising sales in Kenya, more than 80% of Gold Crown’s $50 million in revenue is still generated abroad. The company, which employs about 100 people, selects and packages branded tea for Harrods, the luxury U.K. department store, that is sold in engraved tin boxes, as well as other European tea brands.

Putting too much weight on the local market carries risks. Other Kenyan companies that bet big on local growth, by peddling organic pizzas or healthy juices to the growing middle class, have stumbled. They expanded too quickly in an economy that is still mostly dependent on agriculture and not fully driven by urban consumers.

The company’s effort to expand local production has also hit hurdles. Two years ago, the government confiscated land Gold Crown had bought to build a bigger factory in Mombasa because it wanted to construct a railway to the port. The Ahmeds are still waiting for compensation from the government.

Meanwhile, new machinery they had bought in anticipation of moving to a bigger space is sitting idle in the old factory, wrapped in plastic.

Despite these setbacks, Mr. Ahmed said the company intends to sell both at home and abroad and is now working on bringing its fare to other Africans. Gold Crown is already exporting to Sudan and Ethiopia, and in January, it secured clearance to sell in Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country.

- Previous U.S. Starts Deploying Thaad Antimissile System in South Korea, After North’s Tests

- Next Expelled N. Korea envoy in final verbal blast at Malaysia