Malaysia Posts First Deflation in Over 9 Years: The deflation monster – Opinion

Malaysia Posts First Deflation in Over 9 Years

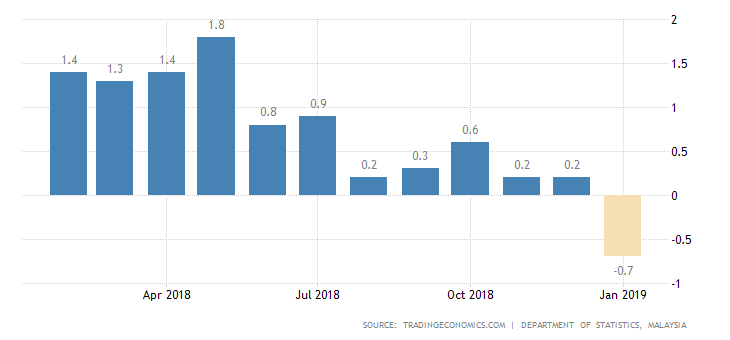

Malaysia’s consumer prices fell 0.7 percent year-on-year in January 2019, after a 0.2 percent rise in the previous month and compared to market consensus of a 0.2 percent drop. It was the first decline in consumer prices since November 2009, mainly due to a slump in cost of transport on cheaper fuel. Also, prices decreased for miscellaneous, communication, recreation and culture while they rose faster for food products.

Year-on-year, prices fell primarily for transport (-7.8 vs -2.0 percent), namely fuels, given that authorities recently changed its fuel subsidy model and domestic fuel prices are now set weekly to reflect moves in global oil prices quicker. Also, cost declined for clothing and footwear (-3.3 percent vs -3.2 percent); health (-0.5 percent vs -0.4 percent); recreation services & culture (-0.4 percent vs -0.2 percent) and furnishings, household equipment & routine maintenance (-0.3 percent vs 0.1 percent); communication (-1.2 vs -1.3 percent); and miscellaneous goods & services (-2.4 percent, the same as in December).

In addition, inflation eased for education (0.9 percent vs 1.1 percent) and restaurants and hotels (1.2 percent vs 1.6 percent). Meantime, inflation was steady for both housing, water, electricity, gas, & other fuels (at 2 percent) and alcoholic beverages & tobacco (at 1.1 percent).

On the other hand, prices of food & non-alcoholic beverages went up by 1.0 percent in January, accelerating from a 0.7 percent rise in a month earlier. The increases were driven by a rise in prices of food away from home (3.3 percent vs 2.7 percent in December), meat (2.4 percent vs 1.0 percent), fruits (1.4 percent vs 0.5 percent), and fish & seafood (1.2 percent vs -0.1 percent).

Core consumer prices rose 0.2 percent year-on-year in January, compared to a 0.4 percent gain in a month earlier and reaching the fifth straight month of rise.

On a monthly basis, consumer prices went down 0.5 percent in January, following a 0.1 percent rise in the preceding month and marking the first monthly decrease in seven months.

The deflation monster

By Datuk Dr. John Antony Xavier

March 1, 2019 @ 12:00am

AT last some relief, just like the feeling after a torrential downpour following an exceptionally sweltering day!

After nearly 10 years of rising prices, Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng recently announced that the consumer price index, or CPI, had declined by 0.7 per cent in January. This fall is in comparison to the inflation rate in January 2018.

Having suffered incessant price increases previously, consumers have greeted this announcement favourably. The government, too, is happy. The CPI fall helps it to keep its election promise of easing living costs. There have been a number of factors that, in combination, account for this welcome fall in prices, or deflation.

First, is the repeal of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and its replacement with the Sales and Services Tax, or SST. The product coverage of the GST was 52 per cent of goods and services. However, the SST is narrower in scope as it applies to only 28 per cent of goods and services. Given this limited coverage, the impact of the SST on prices has accordingly been muted. Sure enough, some 70 per cent of products posted price falls of between 10 and 40 per cent since the implementation of the SST. Stricter enforcement against profiteering following the introduction of SST has also contributed to falling prices.

Second, there have been major price falls in some 40 per cent of the goods and services that constitute the basket that is used to compute the CPI. This basket contains products and services on which an average consumer spends money throughout the year. They include groceries, clothes, rent, electricity, telecommunications, recreational activities and fuel.

Energy and fuel comprise nearly a quarter of the CPI basket. Since early this year, the government has reintroduced the weekly price-float to reflect global crude prices at the pump. Accordingly, retail prices have fallen by as much as 13 per cent in tandem with the global drop in crude oil prices.

Comprising roughly 15 per cent of the CPI basket, communications and entertainment expenditures have registered a drop following, among other things, massive falls in broadband prices.

Third, productivity increase has played a role in precipitating a price fall. Although not as handsome as previous years, labour-productivity growth last year was about four per cent. This lowered the cost of production, thereby lowering the prices of final products.

Lastly, given the fears of an impending economic slowdown, coupled with sustained falls in the stock market, consumers might have begun to tighten their expenditure-belt to save for the “rainy” day. Household debt, comprising 84 per cent of the gross domestic product, has also constrained consumer enthusiasm to spend with reckless abandon.

However, falling prices are a bane to businesses. This is because businesses would have sourced their raw materials at higher prices. And at the point of sale of their wares, they are confronted with falling prices and possible losses. This situation will be compounded if consumers perceive that deflation is permanent. If so, they will withhold expenditure in the hope of buying at a lower price tomorrow.

When such a turn of events happens, businesses will have little incentive to invest in expanding production capacity. The decline in investments and consumption then impacts on employment and economic growth. It is for this reason that the United States, European Union, United Kingdom and Japan have targeted a moderate two per cent inflation rate.

Deflation, too, blunts the efficacy of monetary policy to revive an ailing economy. Falling prices cause real interest rates to rise (interest rate minus inflation rate). That motivates people to save more. It dims the prospects of reducing interest rates to encourage greater spending.

With households and businesses saving rather than spending, economic confidence can begin to wobble. If unchecked, continued deflation can spark a recessionary spiral as was the case with Japan in the 1990s.

As it increases the value of nominal debt, deflation redistributes wealth from debtors to creditors. And if creditors have a lower propensity to consume than debtors, then that, too, will cause aggregate consumption to shrink with deleterious effects on the economy.

For these reasons, deflation is more harmful than inflation. Should we then be worried about deflation? We think not. Our inflation rate is stable. Grocery prices have consistently risen. They grew by one per cent in January. It should cushion any falls in the other components of the CPI.

The market predicts a one per cent inflation rate this year and two to three per cent beyond. The main factor spiking inflation will be crude-oil price rises.

In the medium-term, oil prices are expected to rise on account of US sanctions on two Opec countries — Iran and Venezuela. Opec has also exercised output restraint. Plunging stockpiles and global uncertainties add to this combustible mix to spark crude-oil price increases.

Notwithstanding, we should be wary of the deflation monster. The longer-term impact of higher oil prices would be deflationary, as higher oil prices depress growth. Dampened growth will invariably apply a downward pressure on prices. This may be compounded by the relentless pursuit of the government to contain the cost of living.

Should a deflationary spiral begin, the government should be prepared to intervene quickly to restore confidence in the economy.

In the meantime, let’s enjoy the windfall!

The writer, a former public servant, is a principal fellow at the Graduate School of Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

- Previous The Changing Face of North Kore

- Next Tun M: Gov’t aware of people’s hardships. ‘Bossku’ promotes slave mentality