On Globalization, China and Trump Are Closer Than They Appear

Chinese President Xi Jinping went to Davos to praise globalization. Newly elected U.S. President Donald Trump went to Washington to bury it.

“Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room,” Mr. Xi told the grateful elites in Davos last week. A few days later, Mr. Trump retorted: “Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.” Steve Bannon, Mr. Trump’s top strategist, suggested comparing the speeches side by side: “You’ll see two different world views.”

But appearances can be deceptive. Mr. Trump’s first week in office suggests the world views of Mr. Xi and Mr. Trump may actually have more in common than they seem, potentially bad news for the rest of the world.

China never bought into the liberal Western model of globalization, that market forces should operate across borders largely free of national government interference. China subordinates market forces and trade relations to the state’s overarching view of the national interest. Mr. Trump displays a similarly nationalistic approach to the world: He withdrew the U.S. from the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership this week and imposed new restrictions on foreign entrants; and plans to build a wall along the Mexican border and tax companies that outsource production.

Mr. Xi’s “fundamental political orientation is nationalist, not globalist,” says Andrew Batson of Gavekal Dragonomics, a China-based research firm. He says that was also true of Deng Xiaoping, who opened China to the world in 1979. He pursued what made China better off with no ideological commitment to free markets or trade for their own sake. “Xi is very much in that tradition. His slogan is really, making China great again.”

This point can be found buried amid the platitudes and proverbs in Mr. Xi’s Davos speech: China has pursued the “development path that suits itself” and refuses “to blindly follow” others.

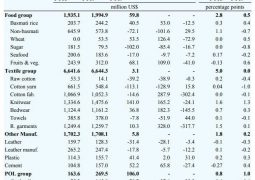

That path meant welcoming foreign investment while using the leverage of its giant market to transfer expertise and technology to Chinese companies in the process. It meant using subsidies, licensing restrictions, government procurement and countless other policies to restrict foreign competition with Chinese national champions, from automobiles to bank cards. It meant holding its currency down so as to sustain large trade surpluses.

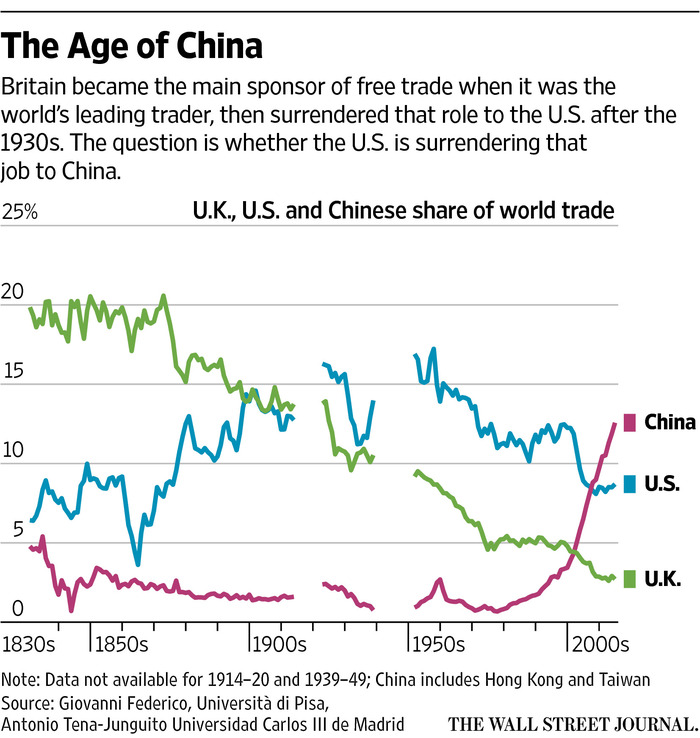

China has retraced the path of previous global economic hegemons. As Ha-Joon Chang, a free-trade skeptic at the University of Cambridge has written, Britain didn’t adopt free trade until the 1800s, when it had become the world’s undisputed economic power. The U.S. similarly kept tariffs high until after World War II. That doesn’t prove protectionism caused industrialization; investment, private property rights and literacy mattered far more. But free trade is politically easier to sell from a position of strength.

While China once had doubts about globalization, Mr. Xi calls it “the right strategic choice.” It has allowed China to industrialize and lifted millions out of poverty while retaining the capacity to favor its own companies at home.

“China likes the current rules because they constrain others more than China,” says Brad Setser, an international economist at the Council on Foreign Relations. The question, Mr. Setser says, is whether, like Britain and the U.S. before it, China is now “confident in its ability to compete and has graduated from infant industry protection. I’d believe that more strongly if China wasn’t so aggressively pursuing industrial policy in areas like semiconductors and aviation.”

American exports to China have jumped since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, and cheap Chinese imports have benefited consumers. But millions of workers lost their jobs from competition with China. And while China largely adheres to its treaty commitments, foreign businesses have grown less optimistic amid regulatory barriers, competition with Chinese companies, and questionable law enforcement, according to the U.S. China Business Council, a trade group.

With occasional exceptions, the U.S. didn’t target particular levels of jobs or the trade balance but sought to establish rules under which its companies could compete freely. The TPP, launched by George W. Bush and negotiated by Barack Obama, wasn’t just supposed to promote growth, but also to solidify strategic relations and create new transnational codes of business conduct.

Mr. Trump may be signaling that era is over. In its place, he is emulating China by using the leverage of the U.S. market and the strong arm of the federal government to extract better terms company-by-company and country-by-country. Like China, he puts national cohesion above the economic and humanitarian case for accepting more immigrants and refugees, and like China, he advocates “noninterference” in others’ affairs. “It is the right of all nations to put their own interests first,” he said. “We do not seek to impose our way of life on anyone.”

Whether the U.S. can replicate China’s success is questionable. China seeks to protect new industries; Mr. Trump is trying to preserve high-wage jobs in mature industries inherently vulnerable to automation or imports. Retaliatory foreign barriers could hit the most successful U.S. sectors such as software, agriculture and aircraft. The U.S.’s traditional commitment to laws and due process is incompatible with the symbiosis between business and government on which China’s “socialist market economy” is predicated.

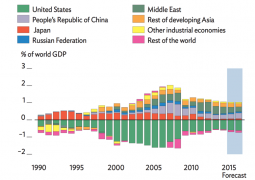

The bigger loss, though, is the rest of the world’s. That’s because last week’s real message isn’t that China is now the guardian of an open global economy; it’s that nobody is.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

- Previous Nikki Haley Arrives at U.N., Vowing to Take Names of Opposing Nations

- Next Turkmens outraged over Tajikistan’s plans to build railway line bypassing Turkmenistan