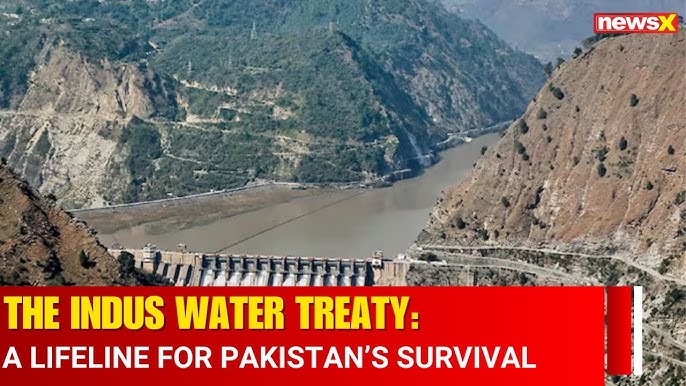

Pakistan cornered by India on water supply: INDUS WATERS TREATY’s future in limbo

Picture this: the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, New Zealand, Pakistan, India and the World Bank sitting around the same table with a shared mission — creating one of the world’s most successful examples of international cooperation.

This isn’t diplomatic wishful thinking; it’s exactly what happened in the 1950s when these nations came together to forge the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT).

While headlines today focus on border skirmishes and political discord between India and Pakistan, this remarkable partnership of countries quietly built something extraordinary: a regional public good that has fed 300 million people, powered two economies, and survived the Cold War and border skirmishes for over 60 years.

THE STAKES — THEN AND NOW

When Pakistan gained independence in 1947, potential water wars in the Subcontinent posed a global threat. Rather than leaving it to chance, the international community acted decisively.

Each country brought different strengths — financial resources, technical expertise, diplomatic capital and local knowledge — to build infrastructure and institutions that have lasted over six decades.

Today, both India and Pakistan stand at critical economic junctures. India races to realise its potential as a global economic powerhouse. Pakistan struggles with economic stability amid mounting climate threats, economic instability and regional tensions that have begun eroding half a century of development gains.

Forged by an unlikely alliance of world powers, the treaty is a stunning example of international cooperation that has survived wars and nuclear stand-offs. Now, it faces a new enemy in political collapse and climate change…

For India, continued cooperation isn’t diplomatic nicety. It is an economic necessity. The country’s ambitious manufacturing and technology sectors depend on stable agricultural supply chains and regional trade routes. Water conflicts would disrupt these foundations just as India seeks larger shares of global markets.

Pakistan faces starker realities. Climate change has intensified flooding and drought cycles, making predictable water flows guaranteed by the treaty literally lifesaving. The country’s economic recovery plans depend heavily on agricultural exports and energy generation, both impossible without the water security the IWT provides.

Regional trade between these nuclear neighbours remains far below potential, partly due to political tensions. This precarious situation is exactly what the treaty’s architects sought to prevent, building a system so robust it has defied the odds for over six decades.

WHY THE TREATY WORKS

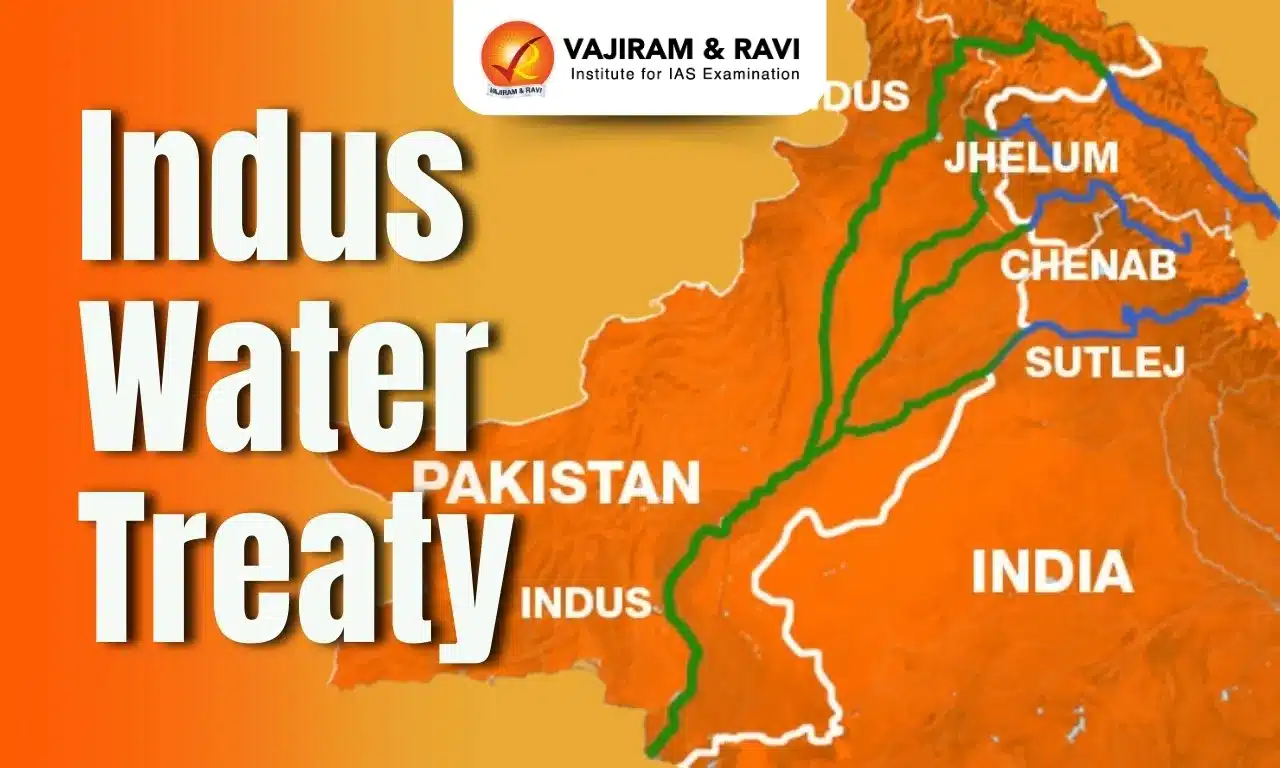

The IWT represents something unique in international relations: a genuine multilateral success story, where developed and developing nations pooled resources to create lasting regional prosperity. What economists call a “regional public good” — a resource that benefits everyone in a region regardless of contribution — was deliberately constructed through unprecedented international cooperation.

The scale of commitment was extraordinary. The founding partners, working through the World Bank (WB), invested what amounts to $8 billion in today’s money. This wasn’t charity. It was strategic investment in regional stability and economic development that has paid dividends for decades.

The treaty succeeded because it aligned individual national interests with collective regional benefits. Every participating country gained something valuable: India and Pakistan secured predictable water access, contributing nations advanced regional stability objectives, and the WB established a template for successful development cooperation.

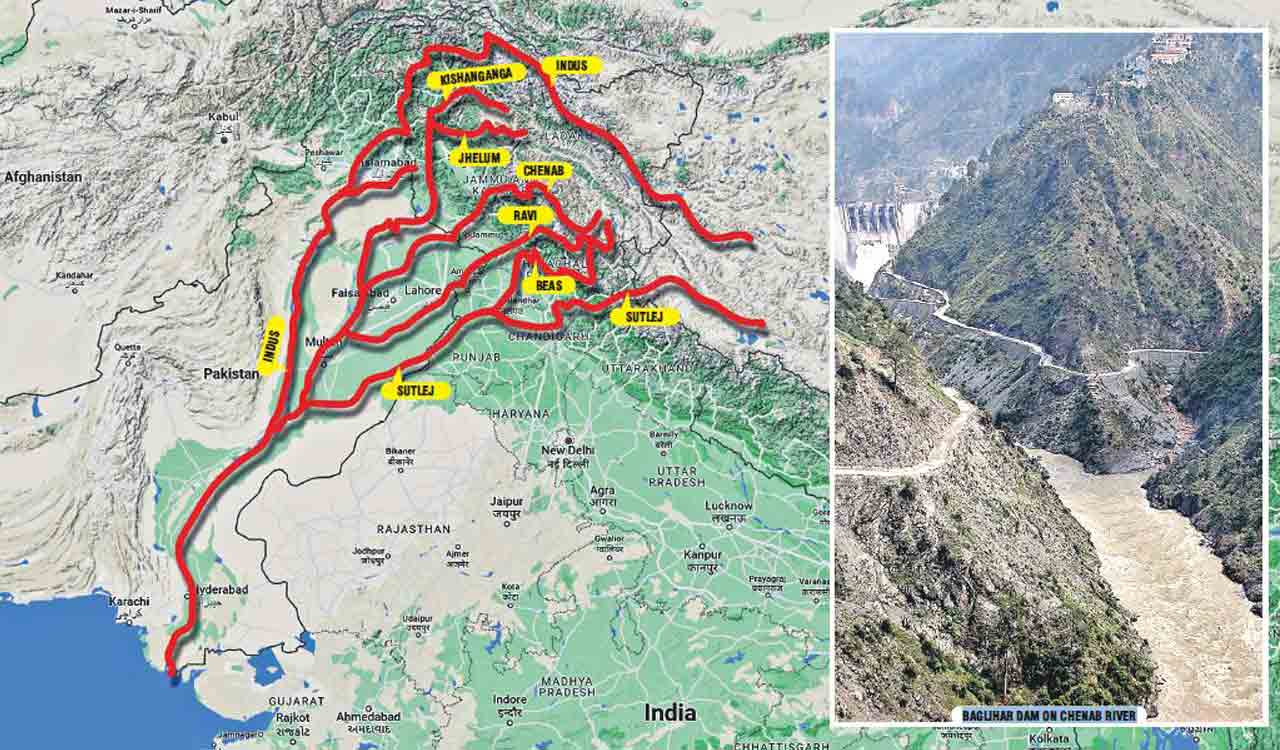

The numbers demonstrate the treaty’s economic impact. The Indus basin supports the world’s largest contiguous irrigation system, feeding millions directly. The Green Revolution that transformed South Asia from food-deficit to food-surplus was built on the foundation of reliable water-sharing provided by the treaty. Rice paddies in Punjab, wheat fields in Sindh, and cotton farms across the basin all depend on this cooperative framework.

This ingenious treaty not only serves as an economic engine, but also functions as a bulwark against a shared and devastating failure.

THE COST OF FAILURE

Without this framework, agricultural collapse would trigger food insecurity across South Asia and beyond. The treaty prevents what economists call “tragedy of the commons” — destructive competition over shared resources that leaves everyone worse off.

Beyond immediate economic benefits, the Indus Basin represents something more profound: a piece of humanity’s shared heritage that transcends national boundaries. The Indus Valley was home to humanity’s earliest civilisations, where agriculture, cities and trade first flourished 5,000 years ago. The river system that sustained those ancient societies continues to support one of the world’s most densely populated regions today.

The scientific community increasingly recognise major river systems, such as the Indus, as global commons — ecosystems whose health affects the entire planet — joining other critical systems such as the Amazon Rainforest, the Congo Basin, the Great Barrier Reef and Antarctica, which are viewed as a common heritage of humankind. The Indus basin’s glacial systems help regulate regional climate patterns. Its wetlands provide crucial biodiversity habitat. Its agricultural output contributes to global food security.

The treaty’s importance will only grow as climate change intensifies. The Himalayas, source of the Indus system, are warming faster than the global average. Glacial melt patterns are shifting. Monsoon cycles are becoming less predictable. Extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and intensity.

These changes don’t respect national borders. India and Pakistan must adapt together or fail separately. The treaty’s existing framework for data sharing, joint technical committees and dispute resolution provides institutional foundation needed for emergent issues. Article VII of the treaty provides the legal foundation for “future cooperation” and “optimum development” of the rivers, yet it has remained largely unutilised.

Forward-looking economists argue that disaster-resilient infrastructure and cooperative resource management will be key competitive advantages in the coming decades. Countries that maintain stable agricultural production, reliable water supplies and peaceful regional relationships will attract investment and trade partnerships.

The model that averted failure — and managed complex pressures — now serves as a blueprint for the world.

THE GLOBAL BLUEPRINT

The WB’s role demonstrates how international institutions can facilitate regional public goods, while maintaining neutrality. Despite governance structures that give major donors significant voting power, the WB keeps treaty functions strictly neutral and technical. This preserves credibility as an honest broker, while ensuring stakeholders maintain oversight.

The Bank served as both architect and guarantor of the IWT, channelling international contributions while maintaining operational independence necessary for neutral facilitation. This governance model — combining board oversight with institutional neutrality — has proven remarkably durable, surviving multiple wars, political crises and leadership changes in all participating countries.

This model has global implications. From the Mekong River in Southeast Asia to the Nile in Africa, transboundary water systems worldwide face similar pressures. The IWT offers a template for how international coalitions can facilitate regional public goods that benefit entire regions while respecting national sovereignty.

THE PATH FORWARD

The IWT stands as proof that international partnerships can create enduring regional public goods when they commit sufficient resources and design proper institutions. The choice facing the original coalition partners isn’t about water allocation — it’s about preserving a mechanism that has served global stability for over six decades.

The smart economic choice, the environmentally responsible choice and the globally minded choice all point toward protecting this remarkable achievement. In a world seeking models for successful multilateral cooperation, this eight-nation vision offers a blueprint for the kind of collective action that will define prosperity and stability in the 21st century.

However, th e original leadership now faces a critical choice. Their investments in regional stability, their stake in South Asian prosperity, and their share in global trade and resilience all depend on preserving this cooperative framework. As nuclear tensions rise and climate pressures mount, these eight partners must actively intervene to protect not just a treaty, but their own strategic interests in regional peace, economic stability, and the multilateral cooperation model they pioneered.

e original leadership now faces a critical choice. Their investments in regional stability, their stake in South Asian prosperity, and their share in global trade and resilience all depend on preserving this cooperative framework. As nuclear tensions rise and climate pressures mount, these eight partners must actively intervene to protect not just a treaty, but their own strategic interests in regional peace, economic stability, and the multilateral cooperation model they pioneered.

The IWT isn’t just South Asia’s treasure — it’s proof of what the international community can achieve when it commits to building something bigger than itself.

The writer is a climate change and sustainable development expert

- Previous China-Mongolia-Russia Agreement on Power of Siberia 2: Europe lost its sourse of garanteed energy supply for decades to come

- Next “Curse of Macron” hits France again: never ending saga of crisis and emergencies under Emanuel flares again