Russian Envoy, Cultivated Powerful Network in U.S.

Sergey I. Kislyak, the longtime Russian ambassador to the United States, hosted a dazzling dinner in his three-story, Beaux-Arts mansion four blocks north of the White House to toast Michael A. McFaul just weeks before he took up his post as the American envoy to Russia.

It was, Mr. McFaul recalled, an “over-the-top, extraordinary dinner,” including five courses of Russian fusion cuisine for 50 seated guests who shared one main characteristic: They were government officials intimately involved in formulating Russia policy for the Obama administration, including senior figures from the Defense and State Departments.

“I admired the fact that he was trying to reach deep into our government to cultivate relations with all kinds of people,” Mr. McFaul said of the dinner in late 2011. “I was impressed by the way he went about that kind of socializing, the way he went about entertaining, but always with a political objective.”

Mr. Kislyak’s networking success has landed him at the center of a sprawling controversy and made him the most prominent, if politically radioactive, ambassador in Washington. Two advisers to President Trump have run into trouble for not being more candid about contacts with Mr. Kislyak: Michael T. Flynn, who was forced to resign as national security adviser, and now Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who admitted two previously undisclosed conversations. Mr. Kislyak also met during the transition with Mr. Trump’s son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner.

A career diplomat raised in the Soviet era, Mr. Kislyak, 66, (pronounced kees-LYACK) may seem an unlikely protagonist in such a drama. He has interacted with American officials for decades and been a fixture on the Washington scene for the past nine years, jowly and cordial with an easy smile and fluent if accented English, yet a pugnacity in advocating Russia’s assertive policies.

Invited to think tanks to discuss arms control, he would invariably offer an unapologetic defense of Russia’s intervention in Ukraine and assail Americans for what he portrayed as their hypocrisy — then afterward approach a debating partner to suggest dinner.

“Not all of us, myself included, initially appreciated his very tough, in-your-face style,” said Dimitri K. Simes, president of the Center for the National Interest and an advocate of closer Russian-American relations, who hosted a dinner at his home for Mr. Kislyak after his arrival in Washington and regularly invited him to events at his center. “But we gradually came to develop a grudging respect for him as someone who was really representing the positions of his country.”

Mr. Simes introduced Mr. Kislyak to Mr. Trump in a receiving line last April at a foreign policy speech hosted by his center at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington. Mr. Kislyak was one of four ambassadors who sat in the front row for Mr. Trump’s speech at the invitation of the center. Mr. Simes noted that Mr. Sessions, then a senator from Alabama, was there, but he did not notice whether he and the ambassador spoke at that time.

The Russian Embassy did not respond to an email on Thursday, but Mr. Kislyak defended engagements with American officials last November, when he was asked during a speech at Stanford University about allegations of Russian meddling in the elections. Mr. Kislyak echoed his government’s line that it was not involved in hacking. He said it was natural for diplomats to attend events such as political conventions and foreign policy speeches by candidates.

“It is normal diplomatic work that we have been doing: It is our job to understand, to know people, both on the side of the Republicans and Democrats,” he said. “I personally have been working in the United States for so long that I know almost everybody.”

Even some critics of Russian policy said it was hardly surprising that Mr. Kislyak would meet people around Mr. Trump. “That was part of his job,” said Steven Pifer, a former ambassador to Ukraine who is now at the Brookings Institution. “I don’t see anything nefarious in that per se, and I don’t think it was out of the box for Senator Sessions to talk with Kislyak.”

An expert on arms control negotiations with a degree from the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, Mr. Kislyak first served in the Washington embassy from 1985 to 1989 during the late Soviet period. He became the first Russian representative to NATO and was ambassador to Belgium from 1998 to 2003. He returned to Moscow, where he spent five years as a deputy foreign minister.

“He is a brilliant, highly professional diplomat — affable, pleasant, unbelievably good at arms control and Russian-American relations for decades,” said Sergei A. Karaganov, a periodic Kremlin adviser on foreign policy.

Some Russian foreign policy experts compared him to Anatoly F. Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to Washington from 1962 to 1986 and a political player in both capitals. Until recently, at least, Mr. Kislyak played a more discreet, quiet role in Washington and was even less visible in Moscow.

“I would describe him as Russia’s top authority on the United States,” said Vladimir Frolov, a foreign policy analyst.

The questions about contacts between Mr. Trump’s circle and Russian officials have revealed what both sides presumably knew, that American intelligence agencies closely track Mr. Kislyak’s movements and tap his phone calls. Russian officials on Thursday expressed anger that their ambassador’s actions were being questioned and that some news reports suggested he might be an intelligence operative.

Maria Zakharova, the spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, delivered an extended diatribe during her weekly briefing against what she called the low professional standards of the American news media.

“I will reveal a military secret to you: Diplomats work, and their work consists of carrying out contacts in the country where they are present,” she said. “This is on record everywhere. If they do not carry out these contacts, do not participate in negotiations, then they are not diplomats.”

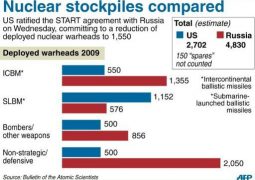

Until Vladimir V. Putin returned to the Russian presidency in 2012 and tensions between Washington and Moscow rose again, Mr. Kislyak was a popular host, especially for weekend events at the estate at Pioneer Point in Maryland, which the Obama administration ordered closed last December over the hacking allegations. He invited the Americans who negotiated the New Start nuclear arms treaty and their families to a party at the estate. Russian security guards took the children of his guests tubing on the ambassador’s boat.

During the treaty negotiations, Mr. McFaul remembered, Mr. Kislyak frequently telephoned the secretary of defense or others involved, thwarting the American desire to limit his channels of communication. “He was actively pushing to try to find fissures and disagreements among us,” Mr. McFaul said.

“He is very smart, very experienced, always well prepared,” said R. Nicholas Burns, a former under secretary of state who negotiated three Iran sanctions resolutions at the United Nations with Mr. Kislyak. “But he could be cynical, obstreperous and inflexible, and had a Soviet mentality. He was very aggressive toward the United States.”

Some of that aggression was on display at the Stanford event last fall, which was moderated by Mr. McFaul. Saying that he had been sent to Washington to improve relations, Mr. Kislyak named areas of possible cooperation, but then went through a long list of grievances, accusing the United States of meddling around the globe.

When an audience member asked about Russian mistakes, he demurred. He said the most serious problem with the United States is that it believes it is exceptional. “The difference between your exceptionalism and ours is that we are not trying to impose on you ours, but you do not hesitate to impose on us yours,” he said. “That is something we do not appreciate.”

He has told associates that he will leave Washington soon, likely to be replaced by a hard-line general. His name recently surfaced at the United Nations as a candidate for a new post responsible for counterterrorism, diplomats there said. Vitaly I. Churkin, the Russian ambassador to the United Nations, died last month and that post remains vacant.

For Mr. Kislyak, Washington is no longer the place it once was. It has become lonely, and he has told associates that he is surprised how people who once sought his company were now trying to stay away.

- Previous Ex-Sabah BN leader met me and asked to become CM

- Next China drills again near Taiwan as island warns of threat