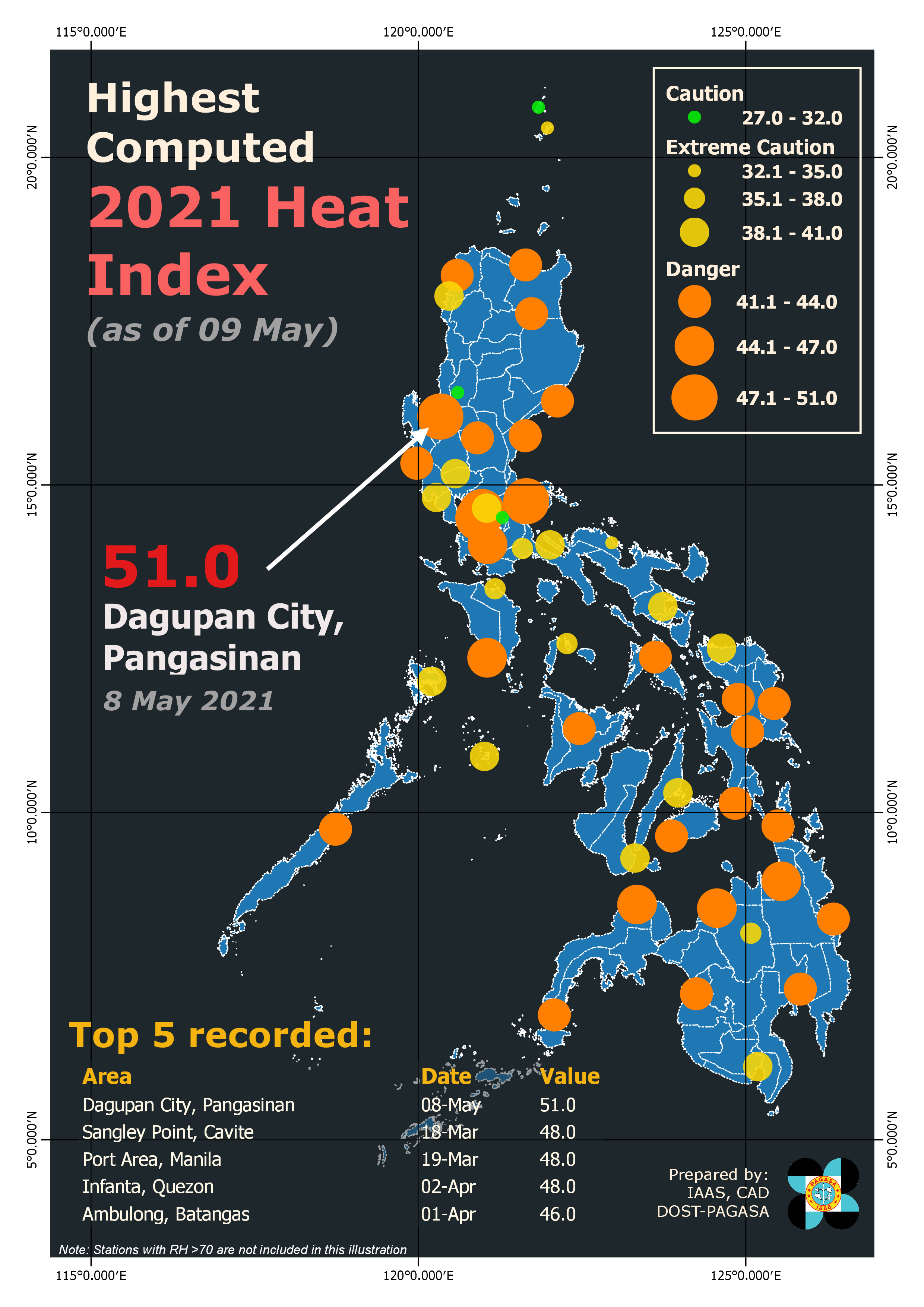

Supercharged storms and rising oceans: 115 mln. Filipinos are feeling rising heat temperatures

Story by Laura Paddison and Giacomo d’Orlando, Photographs and video by Giacomo d’Orlando

Simplicio Calicoy was celebrating his birthday outside his daughter’s home on Maliwaliw Island in the Philippines when strong winds started to whip around them.

The fisherman and his family rushed inside but the gusts began to tear apart the house. Desperate to escape, they found the door pinned shut by the wind, forcing them to squeeze through a window. Calicoy was hit by a steel rod swinging from the ceiling, blinding him in one eye.

When he returned to the village hours later, “there was nothing left,” he said.

Calicoy and his family were lucky to survive Super Typhoon Haiyan, known to Filipinos as Yolanda, one of the most powerful tropical cyclones in recorded history, which devastated the Philippines in November 2013. It killed at least 6,000 people, wrecked tens of thousands of boats and devastated the fishing industry people like Calicoy depend on for their survival.

The Philippines is a cluster of more than 7,600 islands, which lie between the Pacific Ocean and the South China Sea and are home to around 115 million people.

Here, the ocean is everything.

The country boasts 10,400 square miles of some of the planet’s most biodiverse coral reef and its fishing industry is its lifeblood, providing around 1.6 million jobs and the main source of protein for Filipino families.

But this industry is under threat as the human-caused climate crisis raises sea levels and supercharges the storms that increasingly batter the country. The Philippines is one of the most vulnerable places to typhoons in the world. Last year it was pummeled by a record-breaking six consecutive storms in just 30 days.

Decades of environmental destruction make the country even more vulnerable. Mangrove forests, which buffer the coast against storms and provide vital habitats for marine life, have been razed. Some fishers are also turning to Illegal, destructive fishing practices such as trawling, dynamite, and cyanide, as ocean resources dwindle and incomes fall.

The picture looks bleak, but small-scale fishers throughout the country are trying to reverse these trends and preserve the industry for future generations. They are protecting the ocean, restoring ecosystems and rethinking the way they fish.

It’s a tough job and an uphill battle in the face of the escalating impacts of a global climate crisis for which richer countries bear overwhelming responsibility. But it’s yielding results.

There are more than 1,800 marine protected areas in the Philippines — slices of ocean supposed to be safeguarded from human destruction — but corruption, lack of resources, and pressures from the powerful commercial fishing industry have made enforcement a challenge.

Community-based volunteers across the country have responded by setting up Bantay Dagat, or Sea Patrol, where local people patrol marine sanctuaries around the clock from guard houses and boats. They use lights, binoculars and megaphones to warn fishers away and have the power to detain anyone found illegally fishing and hand them over to the police.

Norberto, Ruben and Ramil are part of a sea patrol monitoring the Buluan Marine Sanctuary in the southern Philippines, where illegal fishing used to be rampant. They say their work is having an impact. Would-be illegal fishers are “more afraid because they know there’s law enforcement now, and they don’t want to be fined or end up in jail,” Ruben said.

It’s a win-win for the community, Norberto said. “I can provide for my family while protecting the natural resources for my entire community.”

This kind of work is achingly hard, and those patrolling protected areas can face pushback from their peers.

Neil Montemar, president of the Andulay Fishermen’s Association, which works with local government to protect a 15-acre marine sanctuary, said he initially faced violent reactions. “The fishermen felt they were being denied their cultural rights,” he said.

Attitudes softened, however, as people began to understand the benefits. More volunteers joined. There are now increasing numbers of fish outside the protected areas, and protected areas are now providing income from tourism, he said.

“Everyone should take responsibility and do their part to protect the sanctuary because it is our bank and if we do not take care of it, we will lose everything,” Montemar said.

Another huge issue for the fishing industry, and food security in the Philippines, is the destruction of the country’s mangrove forests.

For decades, mangroves were seen by many as an obstacle to navigation and a source of wood for timber and charcoal. Acres of these coastal jungles, which also store planet-heating carbon, have also been razed to make way for commercial fishponds.

Some communities are trying to reverse this trend, as they increasingly recognize the decline of mangroves is accompanied by a decline in catches. Small-scale fishermen’s alliances dedicated to restoring these ecosystems have sprung up.

Fisherman Roberto “Ka Dodoy” Ballon, leads KGMC, a community organization in Kabasalan set up in 1986. Its aim is to end destructive fishing practices and restore mangroves.

The organization has so far replanted nearly 15,000 acres, and the community has seen results, with numbers of groupers, crabs, clams and shrimps increasing significantly.

Kabasalan is now one of the few places in the Philippines with a productive wild shrimp fishery, increasing the income of fishing families.

Ballon was recognized for his work with the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award, often called the Nobel Prize of Asia, in 2021.

Handayan Island, in the province of Bohol, is also focusing on mangroves. The island was struck hard by Super Typhoon Odette in 2011, with many losing their homes and livelihoods.

Communities started reforesting in 2021, supported by the Zoological Society of London, with the aim of restoring mangroves as a natural barrier to help protect them from destructive storms: their deep roots help absorb energy from storm surges and protect against erosion, while the trunk, leaves and branches above act as a natural wind break.

Small-scale fishers in the Philippines are on the front line of a climate crisis beyond their control: from intensifying storms to ocean warming and acidification that destroys the coral reef on which their fishing depends.

Ultimately, fishing may cease to be the nation’s lifeblood, said Søren Knudsen, director of the non-profit Marine Conservation Philippines. “The future of coastal communities in the Philippines is not based on a fishing ocean economy, but rather tourism and services,” he said.

But for now, coastal communities are battling for survival and showing how important community action can be.

“The whole ecosystem is part of our lives,” said KGMC’s Ballon . “Without the sea, the mangroves, the rivers, we are nothing. We must protect our natural resources, not only for our own benefit, but more importantly for future generations.”

- Previous American woman lives on a cruise ship for 15 years: perpitually

- Next Kumar’s claims have sparked a political storm in India: Modi did not let us to hit back at Pakistani airforse “for political limits”