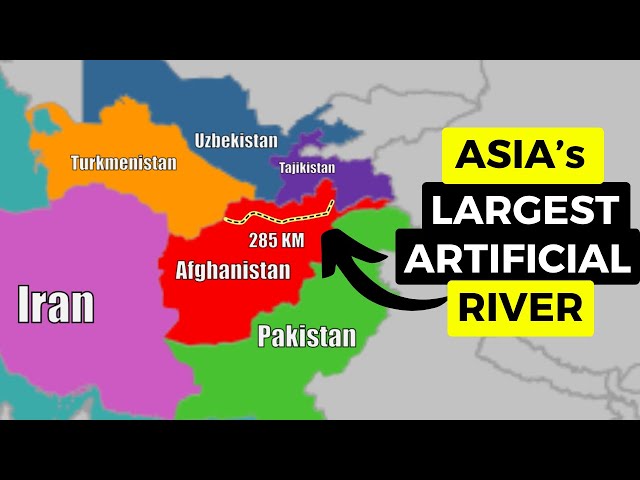

Up to 25% of major river’s water to be taken by Afghans: Taliban bullies Central Asian neighbors with Qosh Tepa Canal building

Progress on the Ground

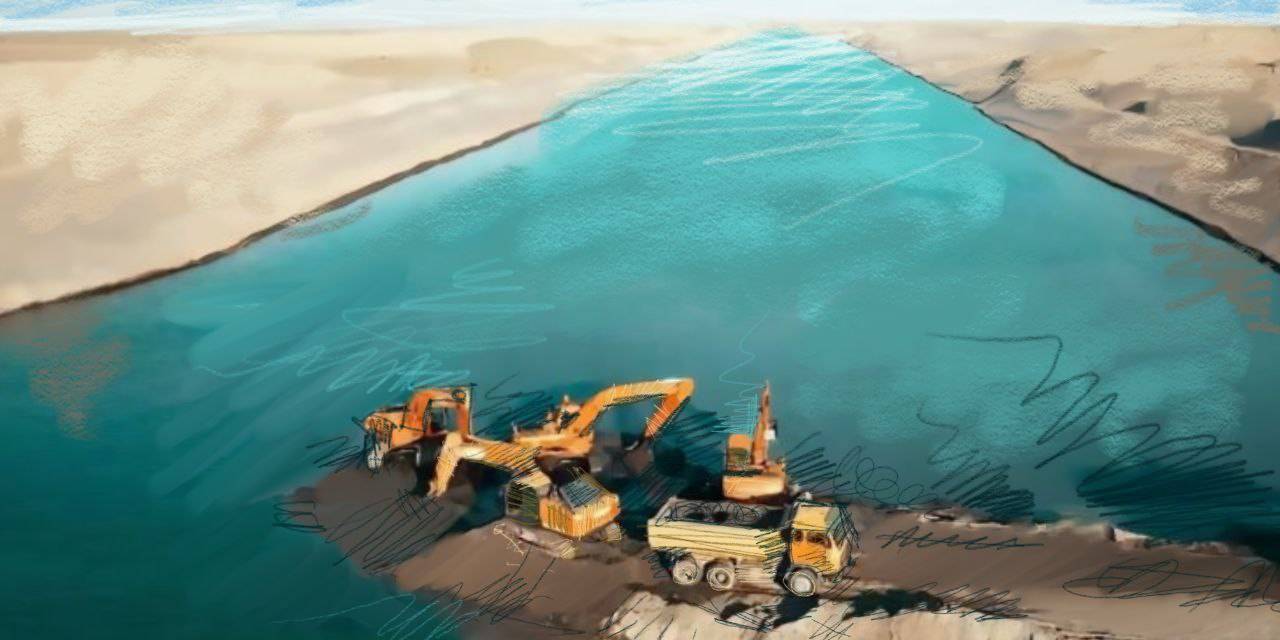

In August, the Afghan authorities stated that 93% of the second phase had been completed. Videos show the canal lined with concrete and stone in some sections, alongside the construction of large and medium-sized bridges to link surrounding settlements. The project spans 128 kilometers from Dawlatabad district in Balkh province to Andkhoy district in Faryab province and involves over 60 contractors, making it one of Afghanistan’s largest infrastructure projects.

Origins and International Support

The canal’s roots trace back to earlier international efforts. While some sources attribute its conceptual origins to Soviet or British engineers in the 1960s, significant development began in 2018 under President Ashraf Ghani. The project was supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Indian engineering firms.

According to the Scientific-Information Center of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (SIC ICWC), a $3.6 million feasibility study was launched in Kabul in December 2018, funded by USAID and conducted by AACS Consulting and BETS Consulting Services Ltd. The study was coordinated with several Afghan ministries, but has not been published.

Following the Taliban’s takeover, the Islamic Emirate held an official inauguration ceremony on March 30, 2022. The full canal is designed to stretch 285 kilometers, measuring 100 meters wide and 8.5 meters deep, and is expected to divert an estimated six to ten cubic kilometers of water annually from the Amu Darya. Afghan media have quoted water management expert Najibullah Sadid, who projected the canal could generate between $470 million and $550 million in annual revenue.

Regional Concerns and Environmental Risks

The project has raised alarm in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan, countries that depend heavily on the Amu Darya for irrigation. Experts at SIC ICWC point out that no environmental impact assessment was conducted for downstream states, nor were they formally notified of the construction, as required by international water conventions.

In December 2022, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev called for practical dialogue with Afghanistan and the international community to strengthen regional water security.

Adroit Associates estimates that the canal could eventually divert up to 13 billion cubic meters annually, nearly one-quarter of the Amu Darya’s average flow.

Environmental risks are also mounting. Analysts warn that Uzbekistan, which relies heavily on the river for agriculture, could face soil degradation and declining crop yields. Turkmenistan, where agriculture accounts for 12% of GDP, may also suffer severe disruptions. Some studies suggest Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan could lose up to 15% of their Amu Darya water supply, with flow volumes potentially down by 30% within five to six years.

Environmental groups caution that, as with the Karakum Canal, the Qosh Tepa may raise groundwater levels, causing widespread soil salinization and the long-term loss of arable land across the region.

A Test for Regional Water Diplomacy

The canal was a key topic at a recent international conference on water security held in Astana, which brought together Central Asian experts, diplomats, and government officials. Speakers stressed the need for coordinated regional strategies to manage transboundary water resources.

“Kazakhstan has no common border with Afghanistan, but we understand that water withdrawal volumes will have consequences,” said Aslan Abdraimov, Kazakhstan’s Vice Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation.

Currently, no formal water-sharing agreement exists between Afghanistan and its northern neighbors. Although Afghanistan is entitled to use the Amu Darya under international law, the Taliban’s unilateral construction of the canal highlights the absence of coordination.

Observers note, however, that Uzbekistan supplies electricity to Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan continues to export gas to the country. These economic ties could provide a foundation for future cooperation on shared water resources.

As the Qosh Tepa Canal nears full operation, its implications reach far beyond Afghanistan’s borders. For Kabul, the project symbolizes sovereignty and a bid to feed its population. For Tashkent, Ashgabat, and Dushanbe, it represents a looming test of water security in a river system already under strain from climate change and overuse. Whether the canal becomes a source of regional cooperation or conflict will depend not only on engineering but on diplomacy, and whether Afghanistan and its neighbors can find a shared framework before water starts to run short.

- Previous Really Taiwan can say “NO”!? Taipei’s ‘no” to move half of chip production to US

- Next Kazakhs try to lock-up for themselves only the Trans-Caspian Transit Corridor to bypass Russian and Uzbek-Turkmen routes

Water has long been one of Central Asia’s most contested resources, shaping agriculture, energy policy, and diplomacy across the region. Recently, Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa Canal project has emerged as a central point in this debate. Promoted by the Taliban as a vital step toward achieving food security and economic growth, the canal also raises alarm bells among downstream neighbors who heavily depend on the Amu Darya River. Now,

Water has long been one of Central Asia’s most contested resources, shaping agriculture, energy policy, and diplomacy across the region. Recently, Afghanistan’s Qosh Tepa Canal project has emerged as a central point in this debate. Promoted by the Taliban as a vital step toward achieving food security and economic growth, the canal also raises alarm bells among downstream neighbors who heavily depend on the Amu Darya River. Now,  five months, raising further concerns among downstream countries about its potential impact on regional water security.

five months, raising further concerns among downstream countries about its potential impact on regional water security.