Hidden agenda of the phantom corridor: Imagining Zangezur to strike at Russia, Iran

Azerbaijan and Armenia’s growing alignment disguises a deeper agenda: expel Russia from the Caucasus and reorient the region to support western interests. Iran, meanwhile, draws its territorial red lines.

By Hazak Yalin

Photo Credit: The Cradle

Photo Credit: The CradleThe 9 November 2020 trilateral agreement, signed by Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, and Russian President Vladimir Putin, ended the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. Its final clause reads:

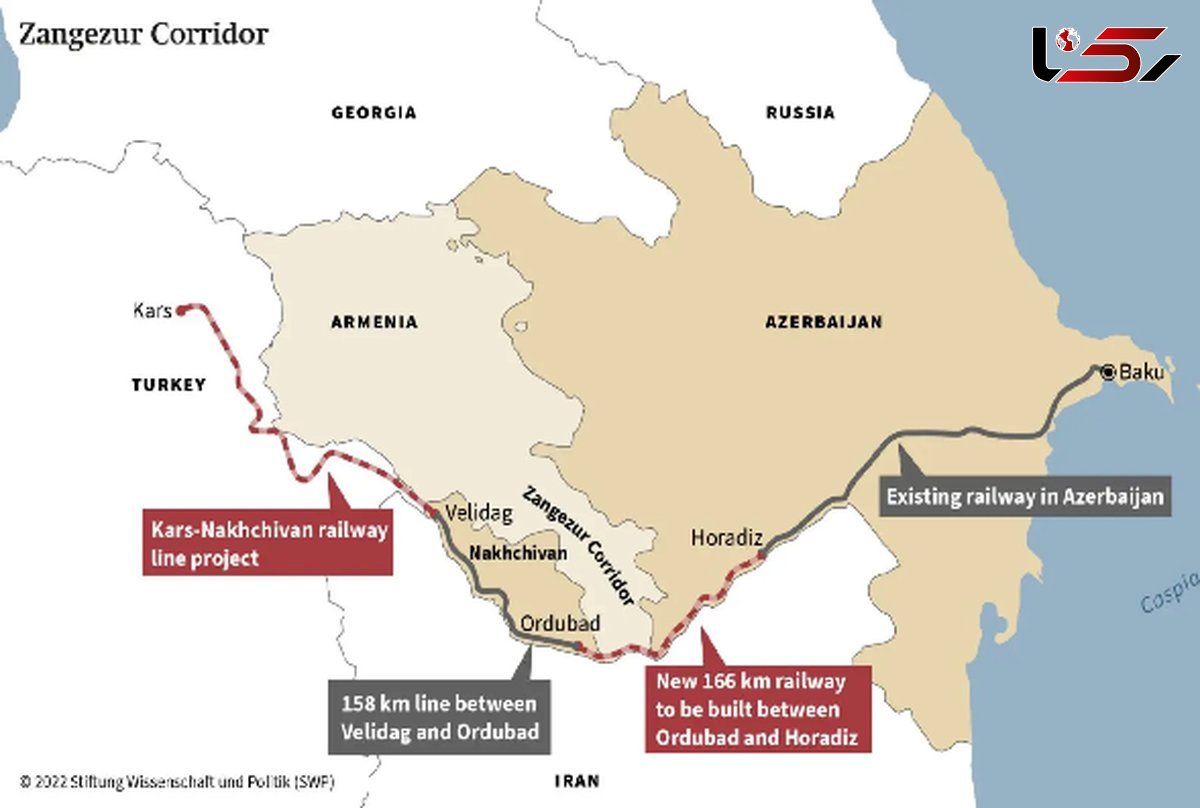

“All economic and transport links in the region shall be unblocked. The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the safety of transport connections between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, to ensure the unimpeded movement of citizens, vehicles, and cargo in both directions. Control over transport connections will be exercised by the Border Guard Service of the Federal Security Service of Russia.”

In the clause, no specific route or corridor is mentioned by name. Based on Moscow’s historic posture, it’s clear Russia envisioned reopening the Caucasus railway—closed since 1992—whose Nakhchivan line ran through Yerevan, alongside road routes via Armenian territory.

But post-war developments reveal that neither Yerevan nor Baku support this approach. Instead, both quietly began favoring an alternative: a corridor hugging the Iranian border – specifically, the Zangezur Corridor, which is about 40 kilometers of land designed to bypass Armenian control.

Three transit options, one political outcome

Contrary to how it’s usually portrayed, Zangezur is not the only route to reconnect mainland Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan autonomous exclave. A second, more rational alternative would be to establish road routes directly through Yerevan or Karabakh.

These routes, if pursued, could forge enduring economic integration between Armenia and Azerbaijan, something far more consequential than a narrow southern corridor that merely skirts the Iranian border and isolates Nakhchivan. Yet this alternative is conspicuously absent from public discourse.

A third, and arguably most functional solution, already exists: the dormant Caucasus railway. If a genuine regional corridor is the goal of all parties—one that would serve both countries and potentially integrate them into broader east-west trade flows—then restoring the railway would be the most logical choice.

The system already physically exists, is more sustainable for freight, and offers long-term connectivity benefits.

But here’s the political snag: Armenian railways are operated by the South Caucasus Railway (YuKJD), a concession held since 2008 by Russian Railways (RZD), under a 30-year agreement. Reopening this route would bolster Russian infrastructure and influence—exactly what both Yerevan and Baku now aim to prevent.

The campaign to exclude Russia

Recent political developments in both Armenia and Azerbaijan leave no doubt about this shared goal of their respective leaders. Aliyev’s government has consciously pursued a policy of provocation, turning tensions with Moscow into a diplomatic standoff. The Azerbaijani president’s broader aim is clear: remove Russia from the regional equation entirely.

Armenia’s Pashinyan, who ascended to power in 2018 via a western-engineered “color revolution,” makes no effort to hide his orientation any longer. His entire governance project is built on sidelining Moscow. Russia’s hesitancy to decisively back Armenia in the last conflict arguably weakened both countries’ regional positions and opened the door for deeper western encroachment.

After the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, the Pashinyan administration was beset by coup claims, dismissed its top generals, froze ties with the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), and sought EU intervention—none of which was incidental. These are clear markers of a westward shift.

In doing so, Pashinyan systematically neutralized all domestic opposition. Most recently, he turned his sights on the Armenian Apostolic Church. Declaring himself the leader of a divine national mission, he accused the clergy of being heretical, anti-national, and enemies of the state. Pashinyan now pledges to personally “cleanse” the institution, accusing Armenia’s Archbishop Acapahyan of displaying a “complete lack of connection and relationship … with Jesus Christ and His teachings.”

This political purge has culminated in  the dismantling of one of Armenia’s most powerful pro-Russian capital networks: the Karapetyan group. Their control over the country’s electric distribution grid—via Armenia Electric Networks—was stripped and brought under state control. For the first time, nationalization became a tool to expel Russian influence.

the dismantling of one of Armenia’s most powerful pro-Russian capital networks: the Karapetyan group. Their control over the country’s electric distribution grid—via Armenia Electric Networks—was stripped and brought under state control. For the first time, nationalization became a tool to expel Russian influence.

This is the context in which the contentious Zangezur Corridor must be understood. Although the easiest solution by far, reopening a Russia-operated railway would contradict the fundamental west-centric geopolitical ambitions of both Baku and Yerevan. For Zangezur to materialize, Armenia must revoke the YuKJD concession. This may appear risky, but it aligns perfectly with the country’s new trajectory. From Yerevan’s perspective, such a rupture can only draw more western capital and endorsement.

Iran’s calculus and the Aras alternative

There is, however, yet another corridor option: the 107-kilometer Aras Corridor, 60 kilometers of which traverses Iranian territory. In September 2023, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan publicly declared that if Armenia blocked Zangezur, the Aras Corridor could be launched instead.

A month later, Azerbaijan began constructing a bridge over the Aras River near the Agbend region. According to the Iranian news agency Tasnim, by January 2024, 15 percent of the roadwork was already complete, with the bridge nearing completion. Plans for a rail line are also underway, all with the Islamic Republic’s approval.

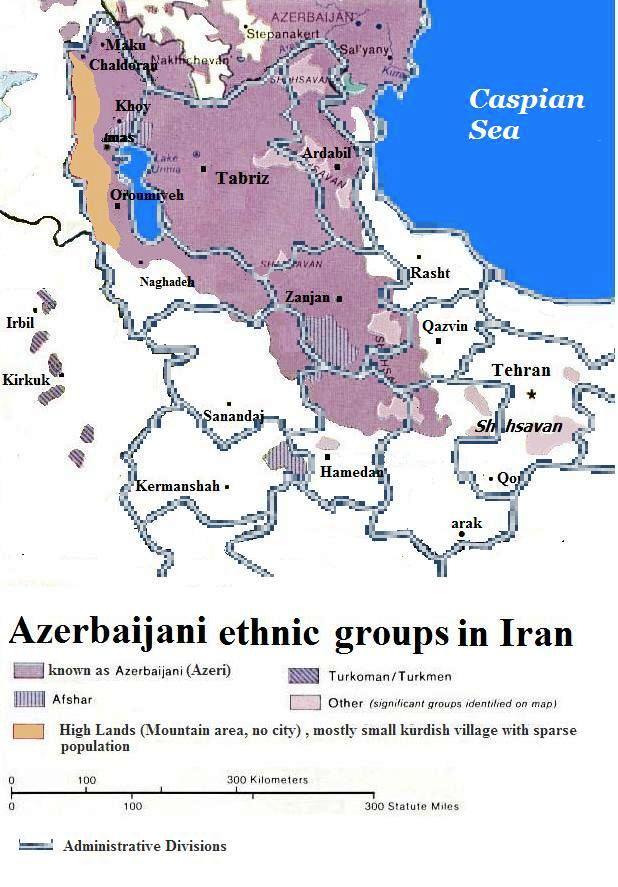

Iran’s posture is unambiguous. In mid-2023, it issued a categorical rejection of any corridor that bypasses Armenian sovereignty. Tehran’s rationale is rooted in strategic depth: if Armenia loses control over its southern border, Iran would be cut off from a historic neighbor and a natural buffer state. This is not mere paranoia—it is a sound geopolitical concern.

Even during the 2020 trilateral talks—before the Zangezur idea was publicly floated—Iran expressed skepticism about corridor politics. Tehran may have intuited Azerbaijan’s intentions or sensed that the corridor issue would eventually gravitate toward bypassing both Armenia and Russia. Iranian diplomats likely viewed Russia’s position as either naïve or ill-fated—asking for what could never happen.

By summer 2024, that skepticism turned to confrontation. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, meeting Pashinyan on 30 July, bluntly stated that the Zangezur Corridor “does not serve Armenia’s interests.”

In September, the Tehran Times reported that the parliament’s National Security Committee declared the Zangezur Corridor a “critical red line for Iran,” further warning that any attempt at altering borders or geopolitical balance would provoke a “strong and serious response.”

On 27 June, Iranian Ambassador to Yerevan Mehdi Sobhani reaffirmed:

“The corridor which is called ‘Zangezur’ does not stem from the interests of Armenia and Iran. For us [i.e. Iran], this is a ‘red line. National Security Council adviser Ali Akbar Velayati added, “We identified the essence of this scheme early and blocked its implementation.”

And this week, on 21 July, Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmail Baghaei reiterated:

“The creation of these passages should not undermine sovereignty and territorial integrity, or internationally recognized borders, and should not cause changes in the geopolitics of the region.”

Russia edged out; the US steps in

Although Moscow continues to reference the 9 November and 11 January agreements and insists they mandate the unblocking of all regional transport routes—not just Zangezur—the reality on the ground tells a different story.

Since 2022, Russia’s strategic focus has shifted to the Ukraine front, leaving it with diminished bandwidth to exert influence in the South Caucasus. The corridor clause—Article 9—has become functionally obsolete.

In the resulting vacuum, a western-aligned regional order is being quietly stitched together. Russian peacekeepers have been expelled. The broader plan to reopen transit routes through Armenia has disintegrated.

Those hoping Aliyev would constrain Pashinyan’s western tilt are watching the opposite unfold: the two states are now reinforcing each other’s anti-Russian agendas.

This makes the 4 July, 2025 image of Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian embracing Aliyev in Hankendi all the more puzzling. Days later, Aliyev and Pashinyan convened in the UAE where talk of a bilateral peace accord, underpinned by their Zangezur dreams, was back in the air.

Tehran is clearly concerned. There are signs the corridor project may be handed to an international consortium—meaning the US or its European proxies. Such a move would plant Iran’s adversaries on its northern flank, displacing Russia and bypassing Iran entirely.

Enter US Ambassador to Ankara Tom Barrack, Washington’s fixer for Caucasus-Levant affairs, who pitched the idea directly: “Lease the Zangezur Corridor to us for 100 years.”

Zangezur: Merely an illusion of economic salvation

So why did Zangezur become the focal point of all parties, in the region and abroad? What changed?

Both Yerevan and Baku agreed in 2020 to reopen “all transport links.” Yet in April 2021, Aliyev suddenly reframed the issue, naming Zangezur as a priority. He justified this shift by citing potential Armenian revanchism. However, the real reason came to light a month later when he stated that the corridor was necessary because Armenian railways were under Russian control.

That confession exposed the game: both governments were targeting Russia, and their supposedly adversarial positions converged into an unspoken alliance. Call it what it is—an anti-Russia coalition masked as pragmatic diplomacy. Aliyev, more than a partner, acts as Pashinyan’s enabler.

And yet, is Zangezur really the economic lifeline its advocates claim?

The idea is often promoted as the linchpin of the “Middle Corridor” connecting China and Europe via Central Asia and Turkiye.

On paper, it promises seamless trade and integration. But there’s a structural problem: the corridor must traverse the Caspian Sea—an inland body governed by collective consent from all littoral states, including Iran and Russia, both of whom are being sidelined in the current political push.

What corridor advocates ignore—or intentionally omit—is that without Russian alignment, no east–west transit route through this region can be operational. The Zangezur project, far from being a neutral infrastructure plan, reflects a calculated effort to marginalize Moscow’s role in the Caucasus.

As long as Baku pursues confrontation and Yerevan remains tethered to western priorities, Zangezur will stay what it is today: a phantom route; not a vehicle for peace or prosperity, but a lever for dismantling Russia’s strategic depth in the region. And, Iran’s geographic red line.

- Previous India and Israel lose their US-backed dominance in Asia

- Next Only after paying off 527,49 bn $ debt: Turks swear to Invest $10 Billion in Kyrgyz Hydropower Projects