Is there room for Turkey in NATO’s future?

Burhanutdin Duran

NATO, a 70-year-old military alliance, faces new strategic questions. The challenges that the organization encounters are diverse. Russian cyber-meddling in Western democracies, China’s move to buy European infrastructure, Washington’s reckless effort to undermine the liberal order, the rise of populism in Europe, terrorism and the refugee crisis are among them. At the same time, there is the question of “what kind of ally” Turkey is.

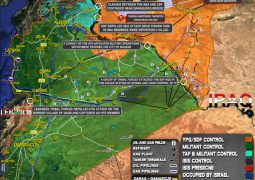

Born to counter the Soviet threat, NATO, now plagued by internal divisions, cannot decide how it should treat Russia today. After the Cold War’s end, the transatlantic alliance expanded into Eastern Europe and the Caucasus instead of cooperating with Moscow. Russia responded to NATO’s expansion with military interventions in Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. At the same time, Russian President Vladimir Putin moved to strengthen his country’s influence over the Middle East, North Africa, the Balkans, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Baltic region and the Sea of Azov. The Russians not only fill the power vacuum, which the United States left behind but also navigates conflicts of interests among European nations and NATO allies skillfully.

The 2014 annexation of Crimea fueled concerns about Russian expansionism in Eastern Europe and the Baltics. Moscow continues to support far-right movements and left-wing populism in Europe. Yet, NATO allies cannot agree on the nature of the Russian threat and the appropriate response thereto. It would be meaningless and impossible to embrace Cold War-era doctrines on the Soviet threat, based on the claim that Russia seeks to surround Europe. Russia, which has no advanced sectors except energy and military equipment, is not a rising power. The only country that could challenge the United States, in the long run, is China. Hence Washington’s efforts to lower the cost of protecting Europe (currently $35 billion per year) and invest in the Asia-Pacific region to contain Beijing.

The United States is already turning on the heat in three key areas: Hong Kong’s status, the Uighur question and China’s artificial islands on the South China Sea. Charles Michel, the European Council’s new president, is worried that the European Union could be “collateral damage” in a brewing “cold war” between the United States and China. Although Britain, the Baltic countries and the Eastern Europeans are eager to treat Russia as a “common enemy,” Germany and France are inclined to see Moscow as a partner. Meanwhile, Washington mounts pressure on Berlin for buying Russian natural gas – as Turkey faces criticism for buying Russia’s S-400 air defense system.

Some Western officials describe Turkey as an unreliable ally. Others say that the Turks are unwanted partners, calling for the country’s removal from the organization. They say that Turkey’s rapprochement with Russia, procurement of the S-400 system and incursion into northern Syria, along with escalating tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean, warrant this treatment. The Turks, in turn, are frustrated with their NATO allies, who failed to support Turkey on Syria-related issues, including terrorism and immigration, and their active support for the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the PKK terrorist organization’s Syrian branch. Indeed, a new dispute is on the horizon, with NATO leaders due to meet in London this week. Retaliating against Washington’s move to block YPG’s designation as a terrorist entity, Turkey just vetoed the Baltic defense plan. In truth, the Turks are not against the Baltic defense plan. But they expect the alliance to express solidarity with Turkey when it comes to terror threats.

NATO needs to reassess its strategic mission and take into consideration Turkey’s security concerns. As Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said, “Turkey is very important for NATO. To understand this, we need to look at the map.”

- Previous Indian doctor abducted, gang-raped, set on fire; nation outraged

- Next Scent of Thailand’s famous fragrant rice is fading